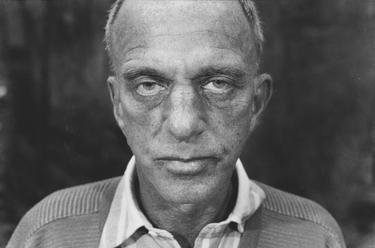

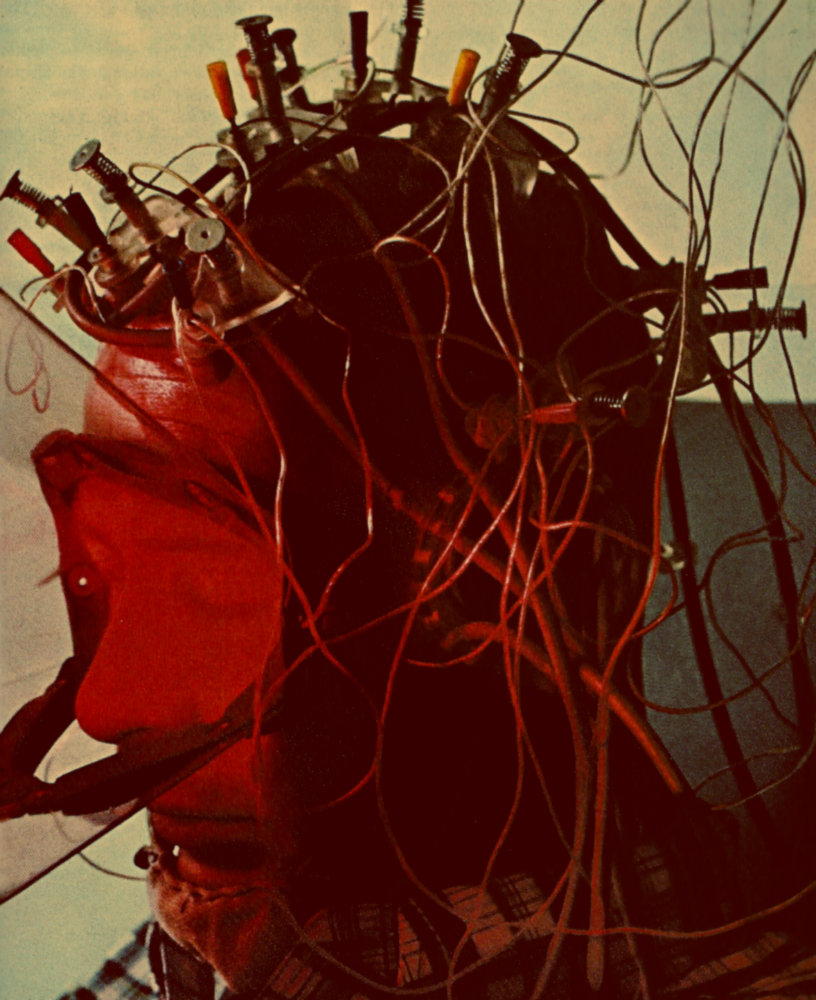

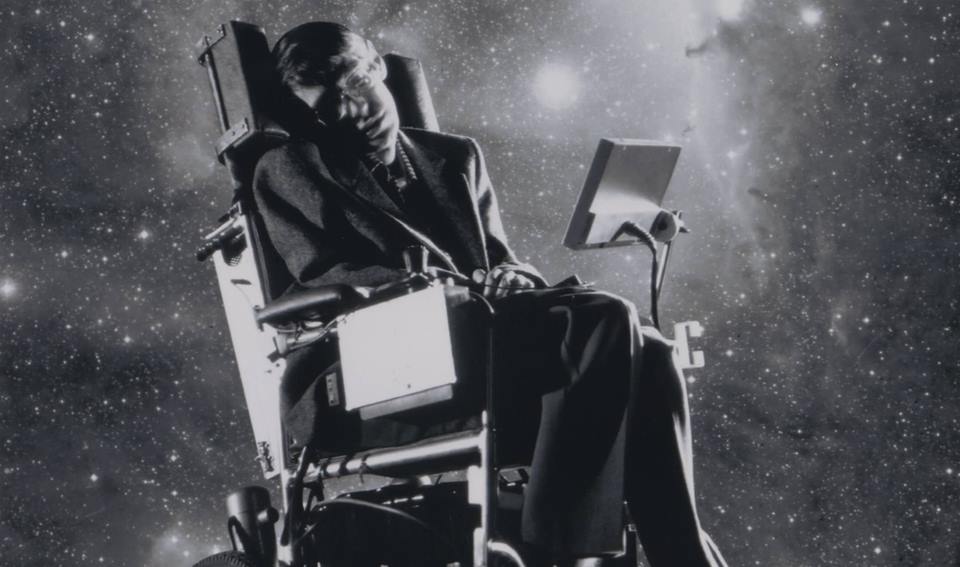

Image by Gerd Ludwig.

There are good reasons for our fixation on the fall of civilization, on the end of us all, and climate change is at the top of the list. But I think along with valid fears, there is fantasy: We simply would like to imagine society toppling, to shuck it off, to start all over again. There’s just something so heavy about modern life, with its clutter and conditions. The weight is too heavy to bear. That’s why we’re always envisioning the apocalypse, staring at ruins (real and virtual), why we feel like the walking dead.

In addition to the endless fictional content available for binge-watching is disaster tourism, and you couldn’t pick a better-worse place than Chernobyl, site of the largest nuclear catastrophe in world history. We made that. How clever we are. From photographers to writers to sightseers with an eye for necropoles, it’s become a hot spot since it cooled somewhat. In a smart Spiegel piece, Hilmar Schmundt and Phil Thoma write insightfully of the disaster porn “created” during the Soviet Era and those who like to watch.

The opening:

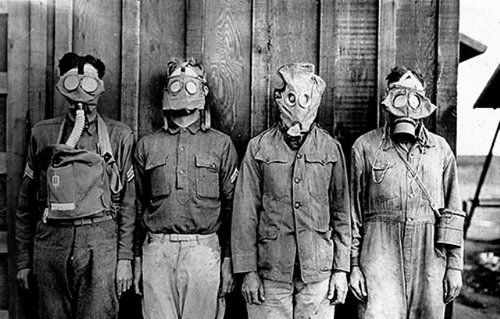

Footsteps crunch across shards of glass and cameras chirp as a group of visitors pushes its way through an evacuated school inside the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Yellowed school books still sit on the desks, Soviet propaganda hangs on the walls and there are several gas masks dangling about. Mobile phone screens glow in the half-light. Time is kept by the ticking of Geiger counters, the hideous heartbeat of gamma rays.

“It’s quite morbid here,” says Alex, from Munich. The well-dressed 20-something takes a few selfies, smiling coolly in front of the backdrop of ruins. “I like offbeat experiences,” he says. Alex works for an online portal and enjoys traveling to exotic places: to the Nyiragongo volcano in Congo, for example, or to the mountain gorillas in Rwanda. He has also taken a weightless flight with an Airbus and joined a tour through North Korea.

Alex is in Chernobyl with a few friends from school and, as a specialist in strange destinations, the trip was his idea. Chernobyl is a powerful brand name: It has become a post-apocalyptical product, simple to consume.

![]](https://afflictor.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/valentina-tereshkova.jpg)