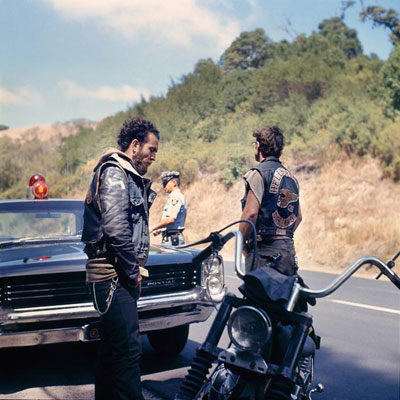

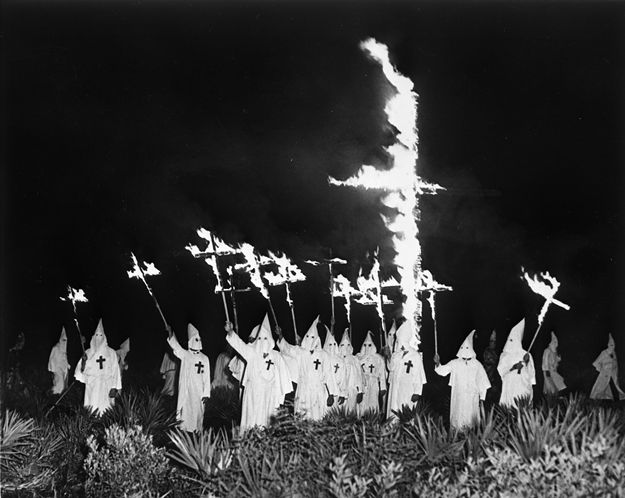

Donald Trump promised during the election to do “unspeakable things” to terrorists, but the most dreadful of all might be what he does to American democracy. Many of his rallies seemed the night before Kristallnacht, with truth and decency only introduced to be mocked, sucker punched and desecrated. Who knows who may be harmed this time, but something awful seems ready to happen. A lot of evil has been unloosed, and some of the ones who helped free the demons are blissfully unaware. The others are overjoyed. America as a beacon for all, a land of liberty, may be a thing of the past.

Illiberal government’s ugly rise is far from just a U.S. issue. Two excerpts follow, one about our mess and another about a parallel travesty occurring in Europe.

The opening of

WARSAW — The Law and Justice Party rode to power on a pledge to drain the swamp of Polish politics and roll back the legacy of the previous administration. One year later, its patriotic revolution, the party proclaims, has cleaned house and brought God and country back to Poland.

Opponents, however, see the birth of a neo-Dark Age — one that, as President-elect Donald Trump prepares to move into the White House, is a harbinger of the power of populism to upend a Western society. In merely a year, critics say, the nationalists have transformed Poland into a surreal and insular place — one where state-sponsored conspiracy theories and de facto propaganda distract the public as democracy erodes.

In the land of Law and Justice, anti-intellectualism is king. Polish scientists are aghast at proposed curriculum changes in a new education bill that would downplay evolution theory and climate change and add hours for “patriotic” history lessons. In a Facebook chat, a top equal rights official mused that Polish hotels should not be forced to provide service to black or gay customers. After the official stepped down for unrelated reasons, his successor rejected an international convention to combat violence against women because it appeared to argue against traditional gender roles.•

The opening of Paul Krugman’s NYT op-ed “How Republics End,” which examines parallels between the fall of Rome and America’s potential faceplant:

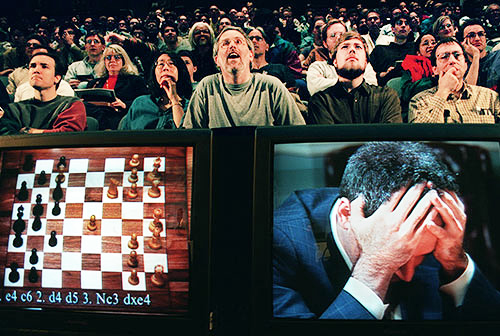

Consider what just happened in North Carolina. The voters made a clear choice, electing a Democratic governor. The Republican legislature didn’t openly overturn the result — not this time, anyway — but it effectively stripped the governor’s office of power, ensuring that the will of the voters wouldn’t actually matter.

Combine this sort of thing with continuing efforts to disenfranchise or at least discourage voting by minority groups, and you have the potential making of a de facto one-party state: one that maintains the fiction of democracy, but has rigged the game so that the other side can never win.

Why is this happening? I’m not asking why white working-class voters support politicians whose policies will hurt them — I’ll be coming back to that issue in future columns. My question, instead, is why one party’s politicians and officials no longer seem to care about what we used to think were essential American values. And let’s be clear: This is a Republican story, not a case of “both sides do it.”

So what’s driving this story?•