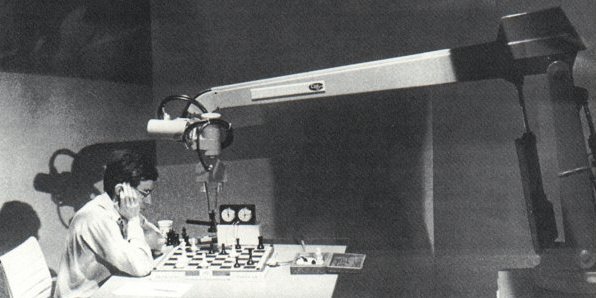

In a 1979 Omni interview, Dr. Christopher Evans spoke with chess player, businessman and AI enthusiast David Levy, who defeated a computer-chess competitor that year but was unnerved by his hard-fought victory. Just six years earlier, he had confidently said: “I am tempted to speculate that a computer program will not gain the title of International Master before the turn of the century and that the idea of an electronic world champion belongs only in the pages of a science fiction book.” Levy knew before the matches at the end of the ’70s were over that our time of dominance was nearing completion.

An excerpt:

Omni:

When did you first begin to feel that computer chess programs were really getting somewhere?

David Levy:

I think it was at the tournament in Stockholm in 1974. One of the things that struck me was a game in which one of the American programs made the sacrifice of a piece, in return for which it got a very good positional advantage. Now, programs don’t normally give up pieces unless they can see something absolutely concrete, but in this case the advantages that it got were not concrete but rather in the structure or nature of the position. It wasn’t a difficult sacrifice for a human player to see, but it was something ! hadn’t expected from a computer program. I was giving a running commentary on the game, and I remember saying to the audience that i would be very surprised indeed if the program made this sacrifice, whereupon it went and made it. I was very, very impressed, because this was the first really significant jump that I’d seen in computer chess.

Omni:

So somewhere around that time things began to stir. To what do you attribute this?

David Levy:

Interest in computer chess generally was growing at a very fast rate, for a number of reasons. First of all, there were the annual tournaments in the United States at the ACM conferences, and these grew in popularity They inspired interest partly because there was now a competitive medium in which the programs could take part. Also, there was my bet, which had created a certain amount of publicity and, I suppose, made people wish that they could write the program that would beat me.

Omni:

How much of this has gone hand in hand with the gradually greater availability of computers and the fact that it no longer costs the earth to get access to one?

David Levy:

Quite a lot. As recently as 1972, in San Antonio, I met some people who were actually writing a clandestine computer program to play chess. They hadn’t dared tell their university department about it because they would have been accused of wasting computer time. They were even unable to enter their program in the tournament, because. If they had they would have lost their positions at the university. Today the situation is dramatically changed, because it is so much easier to get machine time. Now, with the advent of home computers, I think it’s only a matter of time before everyone interested in computer chess will have the opportunity to write a personal chess program.

Omni:

Times have changed, haven’t they? Not very long ago you’d see articles by science journalists saying that computers could never be compared with brains, because they couldn’t play a decent game of chess. There was even some jocular correspondence about what would happen if two computers played each other, and it was argued that if white opened with pawn to king four, black would immediately resign.

David Levy:

This presupposes thai chess is, in practical terms, a finite game. In theoretical terms it is because there is a limit to the number of moves you can make in any position, and the rules of the game also put an upper limit on the total number of moves that any game can involve. But the number of possible different chess games is stupendous — greater than the number of atoms in the universe, in fact. Even if each atom in the universe were a very, very fast computer and they were all working together, they still would not be able to play the perfect game of chess. So the idea that pawn to king four as an opening move could be proved to be a win for white by force is nonsense. One reason you hear these kinds of things is that most people do not understand either the nature of computer programs or the nature of chess. The man in the street tends to think that because chess grand masters are geniuses, their play is beyond the comprehension of a computer. What they don’t understand is that when a computer plays chess, it is just performing a large number ol arithmetic operations. Okay, the end result is typed out and constitutes a move in a game of chess. But the program isn’t thinking. It is just carrying out a series of instructions.

Omni:

One sees some very peculiar, almost spooky moves made by computers, involving extraordinary sacrifices and almost dashing wins, Could they be just chance?

David Levy:

No. Wins like that are not chance. They are pure calculation, The best way to describe the situation is to divide the game of chess into two spheres, strategy and tactics. When I talk about tactics I mean things such as sacrifices with captures, checks, and threats on the queen or to force mate, When I talk about strategy I mean subtle maneuvering to try and gradually improve position. In the area of tactics, programs are really very powerful because of their ability to calculate deeply and accurately. Thus, where a program makes a spectacular move and forces mate two moves later, it is quite possible that the program has calculated the whole of that variation. These spectacular moves look marvelous, of course, to the spectator and to the reader of chess magazines’ because they are things one only expects from strong players. In fact, they’re the easiest things for a program to do.

What is very difficult for a. program is to make a really good, subtle, strategic move, because that involves long-range planning and a kind of undefinable sixth sense for what is ‘right in the position.’ This sixth sense, or instinct, is really one of the things that sorts out the men from the boys on the chessboard. The top chess programs may look at as many as two million positions every time they make a move. Chess masters, on the other hand, look at maybe lifty, so it’s evident that the nature of their thought processes, so to speak, are completely different. Perhaps the best way to put it is that Ihe human knows what he’s doing and the computer doesn’t.

I can explain this with an example from master chess. The Russian ex-world champion Mikhail Tal was. explaining after one game his reasons behind particular moves. In one position his- king was in check on king’s knight one. and he had a choice between moving it to. the corner or moving it nearer to the center of the board. Most players, without very much hesitation, would immediately put the king in the corner, because it’s safer there. But he rejected this move, and somebody in the audience said, ‘Please, Grand Master, can you tell us, Why did you move the king to the middle of the board when everybody knows, that it is safer in the comer?’ And he said, ‘Well, I thought that when we reached the sort of end game- which I anticipated, it would be very important to have my king near the center of the board.’ When they reached the end game, he won it by one move, because his king was one square nearer the vital part of the board than his opponent’s. Now this was something that he couldn’t have seen through blockbusting analysis and by looking ten or even twenty moves ahead. It was just feel.

Omni:

This brings us up against the question of whether or not a computer will ever play a really great game of chess. How do you feel about I. J. Good’s suggestion that a computer could one day be world champion?

David Levy:

Well, ten years ago I would have said, ‘Nonsense.’ Now I am absolutely sure that in due course a computer will be a really outstanding and terrifyingly good world champion. It’s almost inevitable that within a decade computers will be maybe a hundred thousand or a million times faster than they are now. And with many, many computers working in parallel, one could place enormous computer resources at the disposal of chess programs. This will mean that the best players in the world will be wiped out by sheer force of computer power. Actually, from an aesthetic and also an emotional point of view, it would be very unfortunate if the program won the world championship by brute force. I would be much happier to see a world-champion program that looked at very small combinations of moves but looked at them intelligently. This would be far more meaningful, because it would mean that the programmer had mastered the technique of making computer programs ‘think’ in rather the same way that human beings do, which would be a significant advance in artificial intelligence.

Omni:

Which brings us around to the tactics you adopt when playing computers. When did you play your first game against a chess program?

David Levy:

The first one that I remember was against an early version of the. Northwestern University program, and it presented no problems at all. These early programs were rather dull opponents, actually.

The latest ones, of course, are much more intelligent, particularly as they exhibit what you might also describe as psychological characteristics or even personal traits.

Omni:

Could you give an example?

David Levy:

Well, there is this thing called the horizon effect. Say a program is threatened with the loss of a knight which it does not want lo lose. No matter what it does, it cannot see a way to avoid losing the knight within the horizon that it is looking at — say, four moves deep. Suddenly it spots a variation where by sacrificing a pawn it is not losing the knight anymore. It will go into this variation and sacrifice the pawn, but what it does not realize is that after it has lost the pawn, the loss of the knight is still inevitable. The pawn was merely a temporary decoy. But the program is thinking only four moves ahead and the loss of the knight has been pushed beyond its horizon of search, so it is content. Later on, when the pawn has been lost, it will see once again that the knight is threatened and it will once again try to avoid losing the knight and give up something else. By the time it finally does lose the knighl, il has lost so many other things as well that it wishes it had really given up the piece at the beginning. This often brings about a reeling in the program that can best be described as ‘apathy.’ If a program gets into a position that is, extremely difficult because–it is absolutely bound to lose something, it starts to make moves of an apparently reckless kind. It appears to be saying, ‘Oh, damn you! You’re smashing me off the board. I don’t care anymore. I’m just going to sacrifice all my pieces.’ Actually, the program is fighting as hard as it can to avoid the inevitable.

Omni:

That sounds very much like The way beginners get obsessed with defending pieces. But it also sounds as though you’re saying that you feel the program has a mood.

David Levy:

Almost. One tends.to come to regard these things as being almost human, particularly when you can see that they have understood what you. are doing or you can see they are trying to do something clever; In fact, as with human beings, certain tendencies repeat themselves time and again. For example, there are definite idiosyncrasies of the Northwestern University program that one soon comes to recognize. In a particular variation of the Sicilian defense, white often has a knight on his queen four square and black often has a knight on black’s queen bishop three square. Now, it’s quite well known among stronger players that white does not exchange knights, because black can launch a counterattack along the queen-knight tile. Now, I noticed quite often that when playing against the Sicilian defense, the Northwestern University program- would exchange knights. Its main reason was that this maneuver leads to black having what we call an isolated pawn, which, as a general principle, is a ‘bad thing,’ So the Northwestern University program, when in doubt, used to say, ‘I’ll take his knight. And when he recaptures with the knight’s pawn, he has got an isolated rook’s pawn. Goody.’ What it didn’t realize is that in the Sicilian defense, the. isolated rook’s pawn doesn’t actually matter, but having the majority of pawns in the center for black does. So when I played my first match against CHESS 4.5 in Pittsburgh, on April 1, 1977, I deliberately made an inferior move in the opening, so that the program would no longer be following its opening book and wouldn’t know what to do. I was confident that after I made this inferior move the program would exchange knights., which it did, and this presented me with the sort of position that I wanted.•