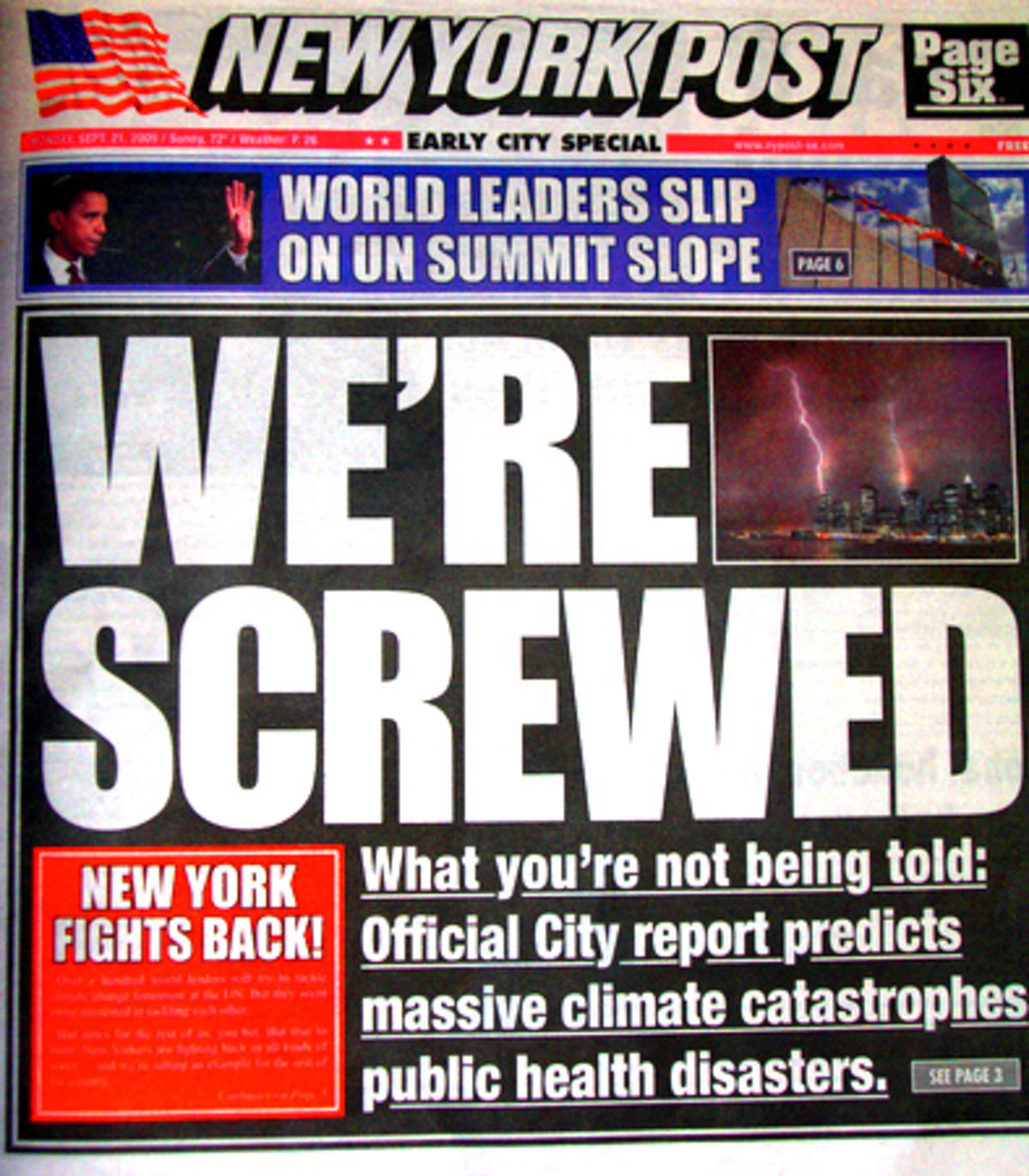

As I’ve argued before, I don’t think wealth inequality is healthy for a society even if everyone’s share is increasing at least a little. Having too much money concentrated in too few hands can lead to uneven power of one sort or another. British Labour politician Peter Mandelson said that he was “relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their taxes.” The thing is, the filthy rich often find a way to bend government to their will, allowing them to unfairly lighten their tax load.

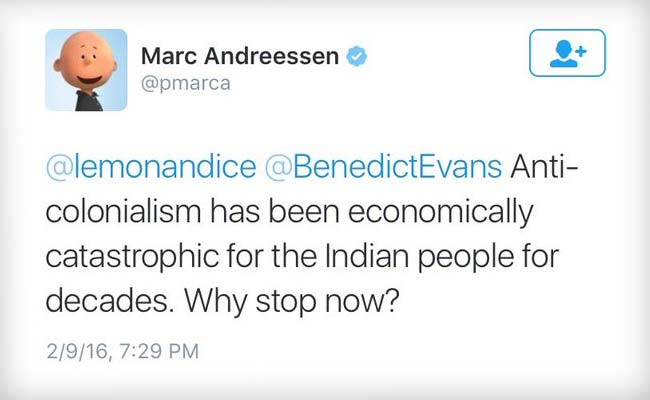

That being said, I don’t reflexively think wealth inequality is the root of all evil. In a Fast Company piece which decimates a strain of Silicon Valley thinking which argues that stark income disparity is actually a good thing, the authors, Jess Rimington, Joanna Levitt Cea and Martin Kirk, present a raft of societal ills linked to wealth inequality. Some seem more plausible than others.

One that stands out as needing closer inspection is infant mortality rate. There were 29.2 deaths per 1,000 U.S. births in 1950, a time of lesser wealth concentration, and 6.1 in 2010 when disparity had ballooned to sickly proportions. Sure, it’s a complicated statistic. There’ve been numerous medical and technological innovations in those six decades, and perhaps without inequality the number would be mercifully lower by now, but that’s not definitely so. If the rate isn’t primarily driven by a huge difference in income, doesn’t that suggest that perhaps a stubborn level of poverty is more the real culprit? Figuring out a way to lift all Americans above a certain floor may be more important than adjusting the ceiling when it comes to this issue. Fairer tax codes could, of course, be part of the answer, but what if such a change made for a more robust middle class but didn’t remedy indigence in any meaningful way? Would that really solve this particular problem?

As I said, I think income disparity is a general negative, but too readily ascribing all societal ills to it may actually help perpetuate some of them.

An excerpt:

The very heart of the Silicon Valley case is the idea that inequality is not inherently damaging. Far better to let large variations of wealth accumulate without constraint, and instead focus on where it doesn’t—where there is poverty—because, as Graham puts it:

“When the city is turning off your water because you can’t pay the bill, it doesn’t make any difference what Larry Page’s net worth is compared to yours. He might only be a few times richer than you, and it would still be just as much of a problem that your water was getting turned off.”

This is a ringing example of where he uses analytical thinking to misdiagnose systemic forces. What he’s implying in this analogy is that the only relevant consideration is the relative wealth of two individuals at the moment a bill needs to be paid. The number of variables left out dwarf those being considered many times over. One simple example would be race. The median wealth of black households in the U.S. is an astonishing 4.5% of that of white households. This, in turn, points to that other glaringly important variable: political influence. As this 2014 Princeton study showed, America is an oligarchy, run by a small group of wealthy and influential individuals; any resemblance to a democracy is merely an illusion. Racial inequality means that African Americans have a lot less of the only political currency that really matters for securing the equal opportunity they so obviously lack right now: actual currency. Graham’s analogy denies these factors entirely. And you can understand why, given that analytical thinking, with its instinct to squash things together, simply can’t cope with multiple variables.

But more importantly, if he’s wrong about the fact that there is nothing inherently damaging about extreme variations in wealth, his entire argument falls apart.

So let’s be absolutely clear: Anyone arguing that income inequality is not damaging to a society is unequivocally wrong.

To be as brief as possible: there is ample evidence, from a library of studies both within and between countries all around the globe, that shows how inequality is strongly correlated with practically any social problem you might like to choose. High levels of inequality are correlated with lower life expectancy, child well-being, educational attainment, social mobility, waste recycling, and, ironically enough for Silicon Valley investors, inventiveness and innovation. It also correlates to higher rates of infant mortality, obesity, mental illness, use of illegal drugs, teenage pregnancy rates, homicide, fighting and bullying among children, imprisonment rates, and levels of mutual trust between citizens.•