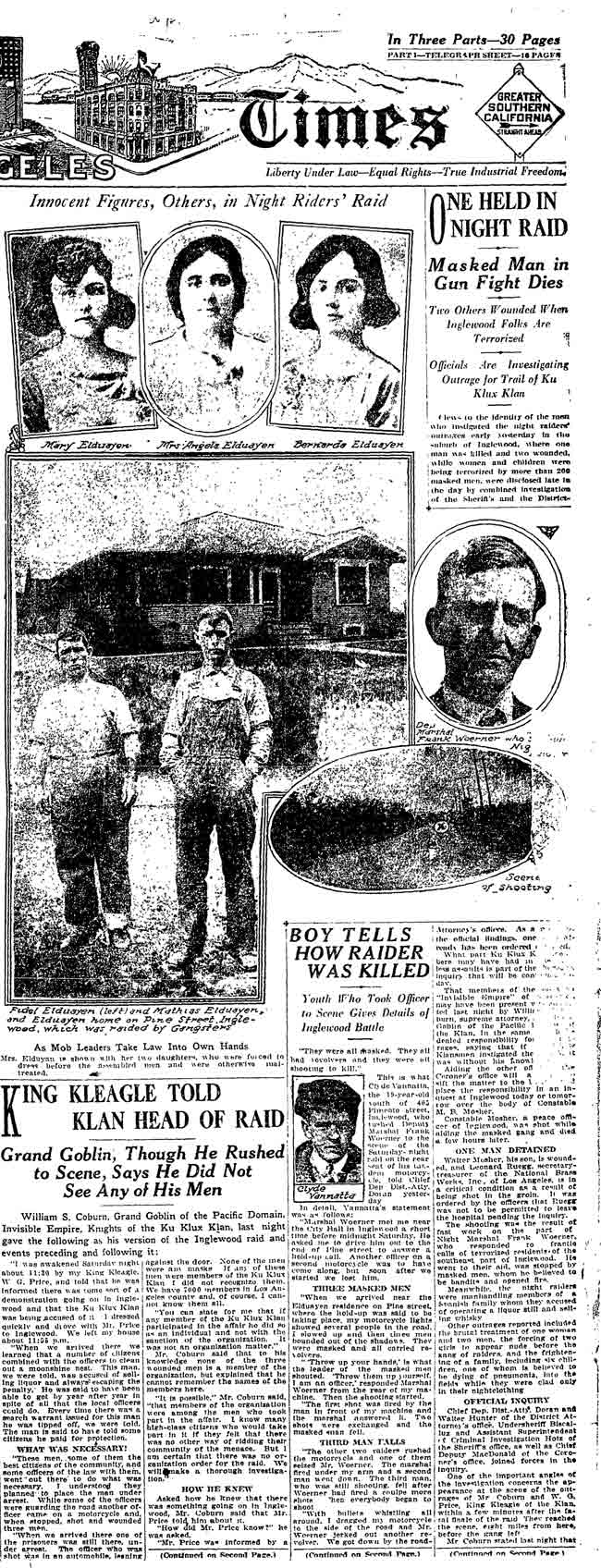

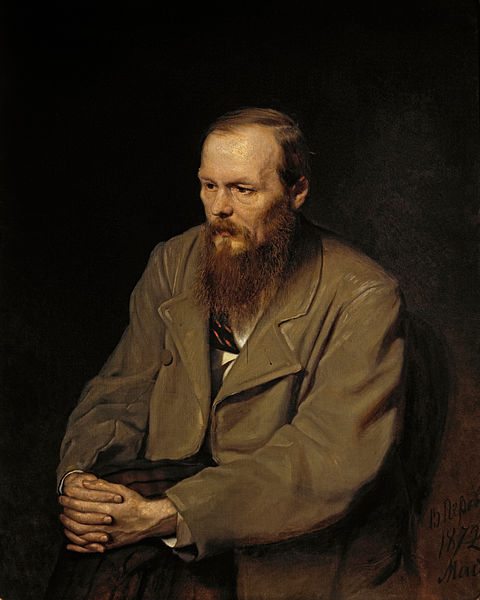

Ilya Khrzhanovskiy’s 4, one of my favorite films of the aughts, was almost indescribably odd. Stranger still, is the follow-up, or the production of it, which has been filming for five years and counting in a Ukranian town, and resembles more a totalitarian state driven by the type of hubris that Herzog and Coppola brought to the jungle, than a mere movie. The opening of Michael Idov’s great GQ article, “The Movie Set That Ate Itself“:

“The rumors started seeping out of Ukraine about three years ago: A young Russian film director has holed up on the outskirts of Kharkov, a town of 1.4 million in the country’s east, making…something. A movie, sure, but not just that. If the gossip was to be believed, this was the most expansive, complicated, all-consuming film project ever attempted.

A steady stream of former extras and fired PAs talked of the shoot in terms usually reserved for survivalist camps. The director, Ilya Khrzhanovsky, was a madman who forced the crew to dress in Stalin-era clothes, fed them Soviet food out of cans and tins, and paid them in Soviet money. Others said the project was a cult and everyone involved worked for free. Khrzhanovsky had taken over all of Kharkov, they said, shutting down the airport. No, no, others insisted, the entire thing was a prison experiment, perhaps filmed surreptitiously by hidden cameras. Film critic Stanislav Zelvensky blogged that he expected ‘heads on spikes’ around the encampment.

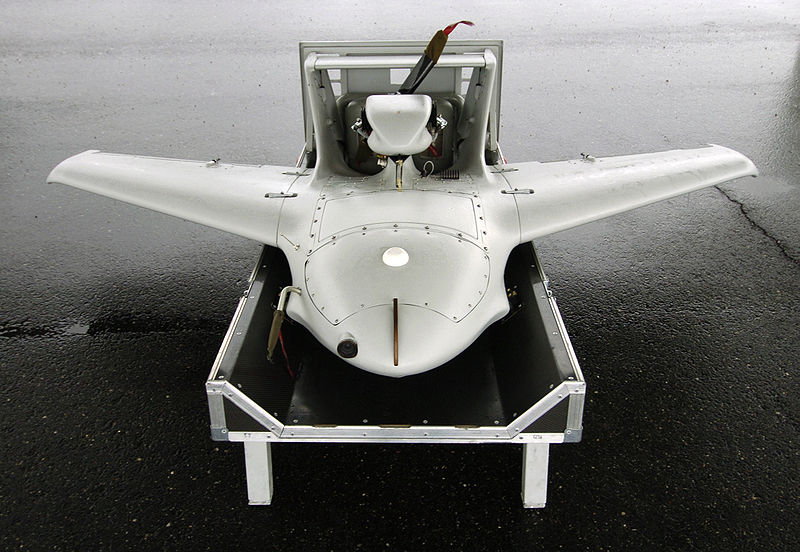

I have ample time and incentive to rerun these snatches of gossip in my head as my rickety Saab prop plane makes its jittery approach to Kharkov. Another terrible minute later, it’s rolling down an overgrown airfield between rusting husks of Aeroflot planes grounded by the empire’s fall. The airport isn’t much, but at least it hasn’t been taken over by the film. And while my cab driver knows all about the shoot—the production borrowed his friend’s vintage car, he brags without prompting—he doesn’t seem to be in the director’s thrall or employ.

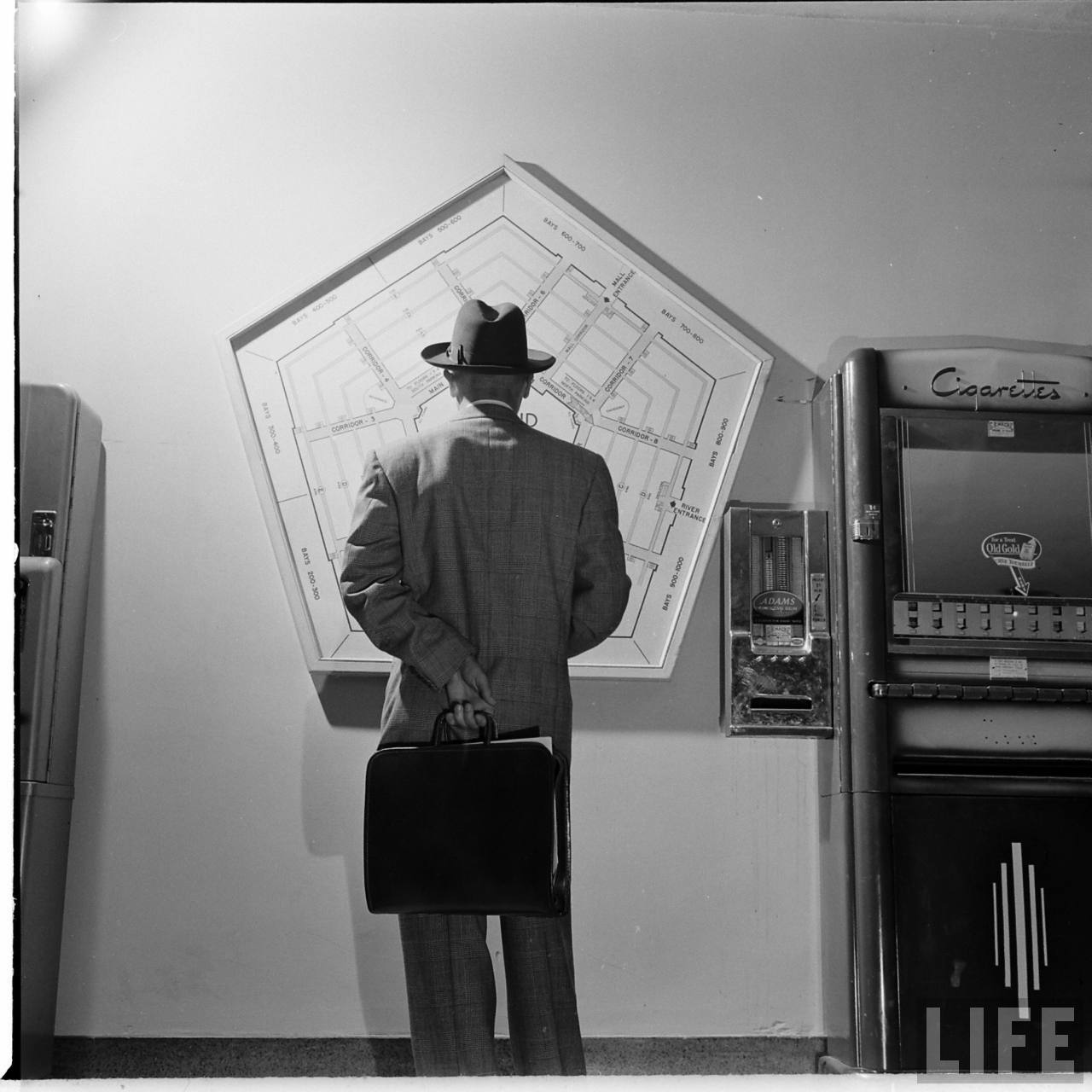

I’m about to write the rumors off as idle blog chatter when I get to the film’s compound itself and, again, find myself ready to believe anything. The set, seen from the outside, is an enormous wooden box jutting directly out of a three-story brick building that houses the film’s vast offices, workshops, and prop warehouses. The wardrobe department alone takes up the entire basement. Here, a pair of twins order me out of my clothes and into a 1950s three-piece suit complete with sock garters, pants that go up to the navel, a fedora, two bricklike brown shoes, an undershirt, and boxers. Black, itchy, and unspeakably ugly, the underwear is enough to trigger Proustian recall of the worst kind in anyone who’s spent any time in the USSR. (I lived in Latvia through high school.) Seventy years of quotidian misery held with one waistband.

The twins, Olya and Lena, see nothing unusual about this hazing ritual for a reporter who’s not going to appear in a single shot of the film—just like they see nothing unusual in the fact that the cameras haven’t rolled for more than a month. After all, the film, tentatively titled Dau, has been in production since 2006 and won’t wrap until 2012, if ever. But within the walls of the set, for the 300 people working on the project—including the fifty or so who live in costume, in character—there is no difference between ‘on’ and ‘off.'”