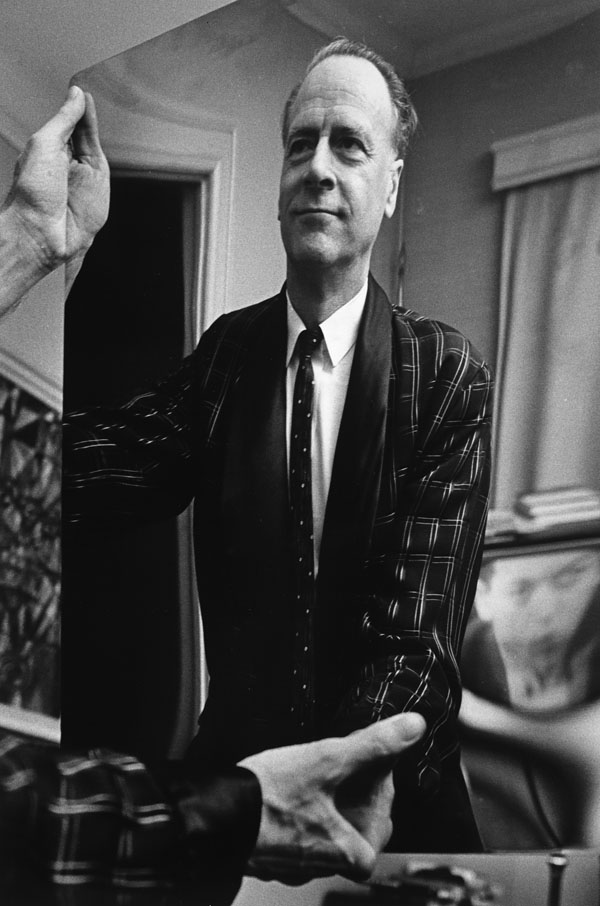

In his New Yorker article this week about Leland Stanford’s famed university, Ken Auletta poses a smart question which has largely gone unasked in the whir of excitement over students and teachers cashing in on start-ups: Has the line between Stanford and Silicon Valley been blurred to the detriment of education? An excerpt, in case you haven’t read it yet, about the big money Valley ties of the university’s brilliant president John L. Hennessy:

“Debra Satz, the senior associate dean for Humanities and Arts at Stanford, who teaches ethics and political philosophy, is troubled that Hennessy is handcuffed by his industry ties. This subject has often been discussed by faculty members, she says: ‘My view is that you can’t forbid the activity. Good things come out of it. But it raises dangers.’ Philippe Buc, a historian and a former tenured member of the Stanford faculty, says, ‘He should not be on the Google board. A leader doesn’t have to express what he wants. The staff will be led to pro-Google actions because it anticipates what he wants.’

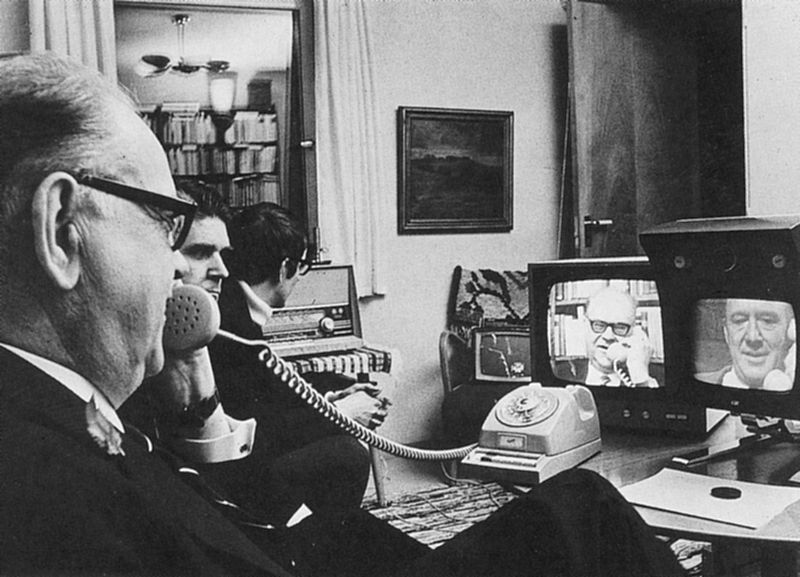

Hennessy has also invested in such venture-capital firms as Kleiner Perkins, Sequoia Capital, and Foundation Capital—companies that have received investment funds from the university’s endowment board, on which Hennessy sits. In 2007, an article published in the Wall Street Journal—’THE GOLDEN TOUCH OF STANFORD’S PRESIDENT’—highlighted the cozy relationship between Hennessy and Silicon Valley firms. The Journal reported that during the previous five years he had earned forty-three million dollars; a portion of that sum came from investments in firms that also invest Stanford endowment monies. Hennessy flicks aside criticism of those investments, noting that he isn’t actively involved in managing the endowment and likening them to a mutual fund: ‘I’m a limited partner. I couldn’t even tell you what most of these investments were in.’

Perhaps because his position is so seemingly secure, and his assets so considerable, Hennessy rarely appears defensive. He knows that questions about conflicts of interest won’t define his legacy, and they seem less pressing when Stanford is thriving. Facebook’s purchase of Instagram made millions for, among others, Sequoia Capital—which means that it made money for Hennessy and for Stanford’s endowment, too.”