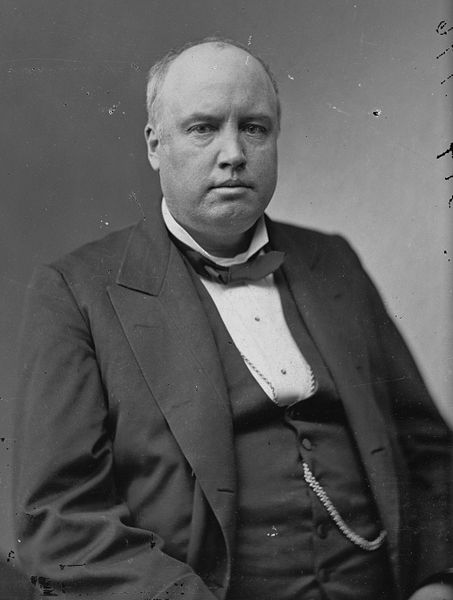

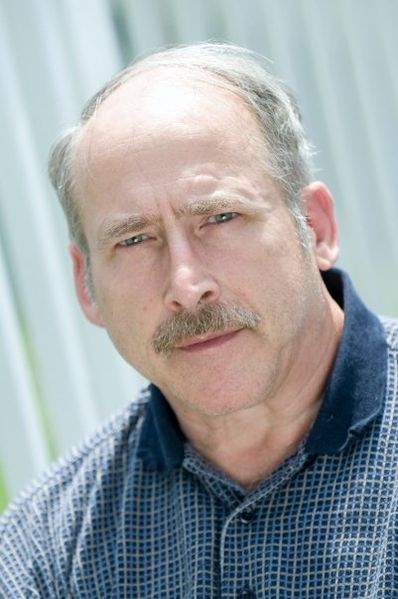

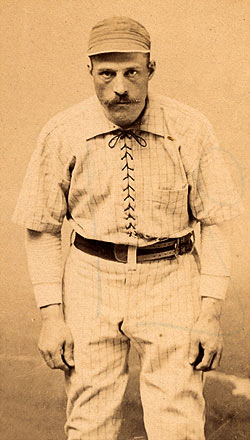

From Susan Jacoby’s beautifully written American Scholar essay about Bob Ingersoll, the “Great Agnostic” of the 19th century, who is largely forgotten today:

Known as Robert Injuresoul to his clerical enemies, he raised the issue of what role religion ought to play in the public life of the American nation for the first time since the writing of the Constitution, when the Founders deliberately left out any acknowledgment of a deity as the source of governmental power. In one of his most popular lectures, titled ‘Individuality,’ Ingersoll said of Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin:

They knew that to put God in the Constitution was to put man out. They knew that the recognition of a Deity would be seized upon by fanatics and zealots as a pretext for destroying the liberty of thought. They knew the terrible history of the church too well to place in her keeping, or in the keeping of her God, the sacred rights of man. They intended that all should have the right to worship, or not to worship; that our laws should make no distinction on account of creed. They intended to found and frame a government for man, and for man alone. They wished to preserve the individuality and liberty of all; to prevent the few from governing the many, and the many from persecuting and destroying the few.

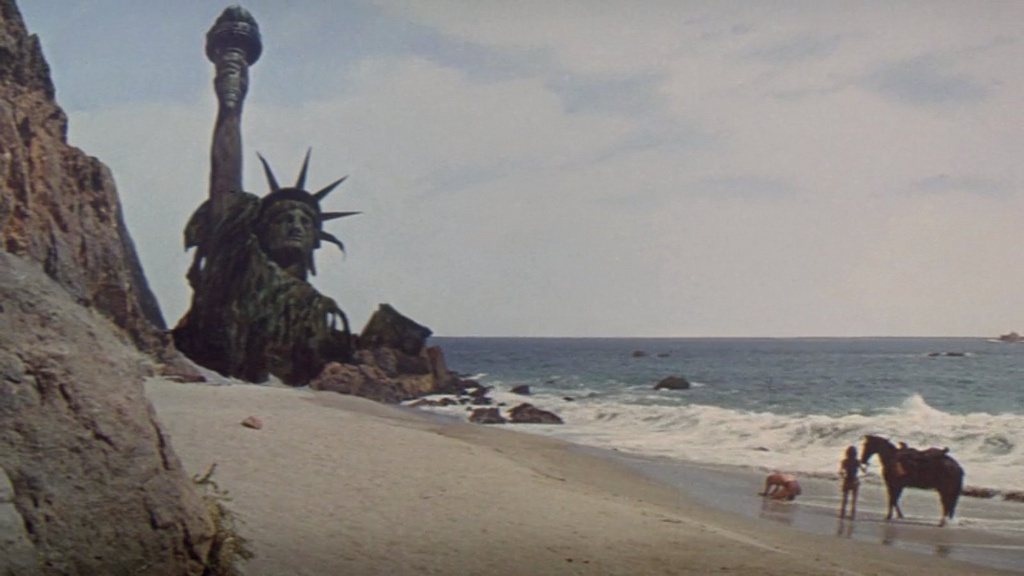

To the question that retains its politically divisive power to this day—whether the United States was founded as a Christian nation—Ingersoll answered an emphatic no. The marvel of the Framers, he argued in an oration delivered on July 4, 1876, in his hometown of Peoria, Illinois, was that they established ‘the first secular government that was ever founded in this world’ at a time when every government in Europe was still based on union between church and state. “Recollect that,” Ingersoll admonished his audience. “The first secular government; the first government that said every church has exactly the same rights and no more; every religion has the same rights, and no more. In other words, our fathers were the first men who had the sense, had the genius, to know that no church should be allowed to have a sword.” A government that had “retired the gods from politics,” Ingersoll declared with decidedly premature optimism on America’s 100th birthday, was a necessary condition of progress.

To 19th-century freethinkers, as to their 18th-century predecessors, intellectual and material progress went hand in hand with abandonment of superstition, and strong ties between government and religion amounted to state-endorsed superstition. Born decades before cities were illuminated by electricity, before the role of bacteria in the transmission of disease was understood, before Darwin’s revolutionary insight that humans were descended from lower animals was fully accepted even within the scientific community, Ingersoll was the most outspoken and influential voice in a movement that was to forge a secular intellectual bridge into the 20th century for many of his countrymen.•