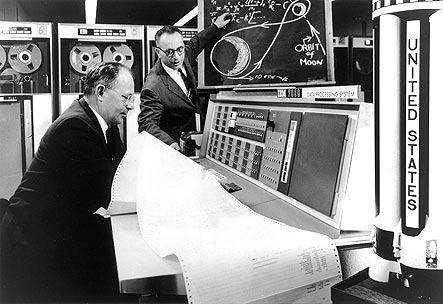

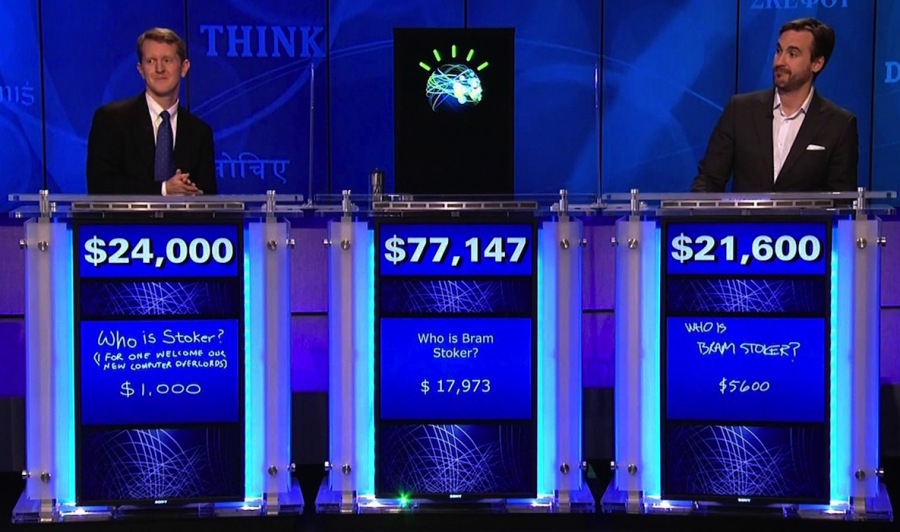

When we transitioned from the oral tradition to the printed word, we outsourced some of our memory. There were concerns about how knowledge would be altered, much as there are now that we’re offloading to computers. Books, of course, were a boon to intelligence, but are there crucial differences in regards to computers, even dangerous ones? Digital Age contrarian Nick Carr believes there are and argues so in a new Atlantic essay.

Carr makes it as difficult as possible on himself, without a straw man in the piece. He begins by arguing that airplane auto-pilot has eroded pilot skills, increasing hazards if the system fails. It’s not an easy debate to have since American commercial airlines almost never crash anymore and certainly far less than in pre-computer days. Of course, that’s not entirely because of automation but also due to an increased understanding of wind shears. But computerization has been an important component to greater safety. Carr makes a case, however, that observation instead of action gradually will degrade our ability to translate information into knowledge. I think we’re just changing over to a new type of knowledge–a necessary metamorphosis–but it’s a compelling article. The opening:

“The first automatic pilot, dubbed a ‘metal airman’ in a 1930 Popular Science article, consisted of two gyroscopes, one mounted horizontally, the other vertically, that were connected to a plane’s controls and powered by a wind-driven generator behind the propeller. The horizontal gyroscope kept the wings level, while the vertical one did the steering. Modern autopilot systems bear little resemblance to that rudimentary device. Controlled by onboard computers running immensely complex software, they gather information from electronic sensors and continuously adjust a plane’s attitude, speed, and bearings. Pilots today work inside what they call ‘glass cockpits.’ The old analog dials and gauges are mostly gone. They’ve been replaced by banks of digital displays. Automation has become so sophisticated that on a typical passenger flight, a human pilot holds the controls for a grand total of just three minutes. What pilots spend a lot of time doing is monitoring screens and keying in data. They’ve become, it’s not much of an exaggeration to say, computer operators.

And that, many aviation and automation experts have concluded, is a problem. Overuse of automation erodes pilots’ expertise and dulls their reflexes, leading to what Jan Noyes, an ergonomics expert at Britain’s University of Bristol, terms ‘a de-skilling of the crew.’ No one doubts that autopilot has contributed to improvements in flight safety over the years. It reduces pilot fatigue and provides advance warnings of problems, and it can keep a plane airborne should the crew become disabled. But the steady overall decline in plane crashes masks the recent arrival of ‘a spectacularly new type of accident,’ says Raja Parasuraman, a psychology professor at George Mason University and a leading authority on automation. When an autopilot system fails, too many pilots, thrust abruptly into what has become a rare role, make mistakes. Rory Kay, a veteran United captain who has served as the top safety official of the Air Line Pilots Association, put the problem bluntly in a 2011 interview with the Associated Press: ‘We’re forgetting how to fly.’ The Federal Aviation Administration has become so concerned that in January it issued a ‘safety alert’ to airlines, urging them to get their pilots to do more manual flying. An overreliance on automation, the agency warned, could put planes and passengers at risk.

The experience of airlines should give us pause. It reveals that automation, for all its benefits, can take a toll on the performance and talents of those who rely on it.”