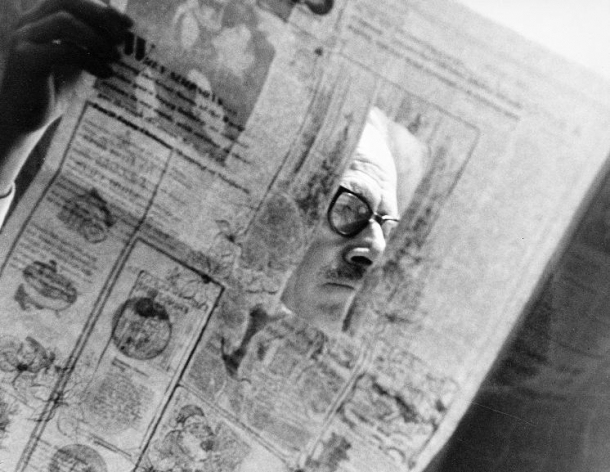

Personalization is good for a lot of things, but democracy isn’t one of them. Yet, I think we’re better off in America during this time of unfettered distribution. My sense is that in the big picture people are better informed now. Not everyone, but more of us. Yes, some still believe in anti-immunization hokum and there are citizens who desperately need Obamacare who think it’s “bad,” but there are ways to now chip away at such notions. Senator Joseph McCarthy thrived for a long time when few controlled channels of distribution, but today he would be treated like just another derp on Twitter.

So algorithms disseminating news concerns me, but maybe not as much as I thought it would a few years ago. From Stuart Dredge’s Guardian report about a SXSW conference which featured Kelly McBride of the Poynter Institute:

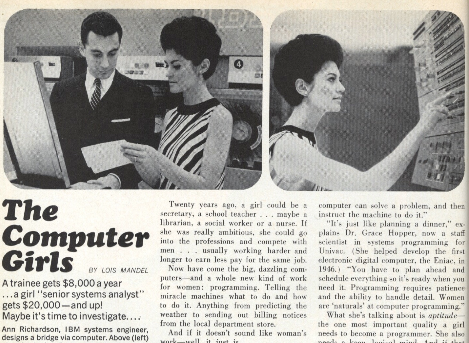

“McBride claimed that in the 20th century, the marketplace of ideas was the professional press, complete with gatekeepers to those ideas in the form of journalists. ‘You either had to be an editor, or had to have access to an editor, or once television came along you had to have access to the means of production,’ she said.

‘The modern marketplace of ideas has completely changed in just the last six or seven years. You can be the first one to publish information,’ she said, referring to the famous first photograph of the plane that landed on New York’s Hudson River, as well as to blog posts that have gone viral.

In theory, then, we’re in a time when anyone can have an idea, publish it and theoretically have it float up to be encountered and considered by the wider population without the permission of those 20th-century gatekeepers.

The challenge: the modern marketplace of ideas is ‘a very noisy place: so noisy that you yourself don’t get to just sort through all of the ideas’ said McBride.

‘If you look at the research on how people get their news now: you often hear this phrase: ‘If news is important, news will find me’ – particularly for millennials. But behind that statement is something really important: if news is going to find you, it’s going to find you because of an algorithm.'”