Carson McCullers being interviewed (pretty poorly) on a ship in 1956. Mostly discusses the stage version of A Member of the Wedding.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Books category.

Tags: Carson McCullers

This Open Culture post about Samuel Beckett driving a young Andre the Giant to school nearly made my brain may explode. An excerpt:

“In 1958, when 12-year-old André’s acromegaly prevented him from taking the school bus, the author of Waiting for Godot, whom he knew as his dad’s card buddy and neighbor in rural Moulien, France, volunteered for transport duty. It was a standing gig, with no other passengers. André recalled that they mostly talked about cricket, but surely they discussed other topics, too, right? Right!?”

Tags: Andre the Giant, Samuel Beckett

Erich Segal was smart and successful, but he didn’t always mix the two. A Yale classics professor with a taste for Hollywood, he wrote Love Story, the novel and screenplay, and was met with runaway success in both mediums for his tale of young love doomed by cruel biology, despite the coffee-mug-ready writing and Boomer narcissism. (Or perhaps because of those blights.) While I don’t think it says anything good about us that every American generation seems to need its story of a pristine girl claimed by cancer–The Fault in Our Stars being the current one–the trope is amazingly resilient.

The opening of a 1970 Life article about Segal as he was nearing apotheosis in the popular culture:

“He looks almost too wispy to walk the 26 miles of the annual Boston Marathon, much less run all that way, even with a six-time Playboy fold-out waiting to greet him at the finish line. But Erich Segal doesn’t fool around. When he runs, he runs 26 miles (once a year, anyway–10 miles a day, other days), when he teaches classics he teaches at Yale (and gets top ratings from both colleagues and students), when he writes a novel he writes a best-seller. Love Story was published by Harper & Row in February and quickly hit the list. With his customary thoroughness Segal was ready: he had simultaneously written a screenplay of the story, and promptly sold it for $100,000. A bachelor (‘with intermittent qualms’), Segal has spent his 32 years juggling so many careers that it worries his friends. Even before Love Story he numbered among his accomplishments a scholarly translation of Plautus and part credit for the script of Yellow Submarine. At this rate, if his wind holds out, he may even win the Boston Marathon.

Love Story is Professor Segal’s first try at fiction, and when on publication day two months ago his editor at Harper & Row called up and said simply, ‘It broke,’ Segal remembers wondering whether he was talking about his neck or his sanity.”

Tags: Erich Segal

My main objection to the 10,000-hour rule is that it cherry-picks particular pieces of research that provide a nice round number for a narrative attempting to make sharp an old saw (“Practice Makes Perfect”). It tells a macro story that doesn’t gibe with the micro, trying to pitch a camping tent over an entire city, stretching the fabric beyond its capacity for coverage.

The cult of Disruption is not dissimilar in how it goes about building its case. In the business world and beyond, radical innovation and its ability to replenish is revered, sometimes to a jaw-dropping extent. In one of my favorite non-fiction articles of the year, “The Disruption Machine,” Jill Lepore of the New Yorker takes apart the bible behind the idea, Clayton M. Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma, which like the 10,000-hour rule, builds its case very selectively and not necessarily accurately. An excerpt:

“The theory of disruption is meant to be predictive. On March 10, 2000, Christensen launched a $3.8-million Disruptive Growth Fund, which he managed with Neil Eisner, a broker in St. Louis. Christensen drew on his theory to select stocks. Less than a year later, the fund was quietly liquidated: during a stretch of time when the Nasdaq lost fifty per cent of its value, the Disruptive Growth Fund lost sixty-four per cent. In 2007, Christensen told Business Week that ‘the prediction of the theory would be that Apple won’t succeed with the iPhone,’ adding, ‘History speaks pretty loudly on that.’ In its first five years, the iPhone generated a hundred and fifty billion dollars of revenue. In the preface to the 2011 edition of The Innovator’s Dilemma, Christensen reports that, since the book’s publication, in 1997, ‘the theory of disruption continues to yield predictions that are quite accurate.’ This is less because people have used his model to make accurate predictions about things that haven’t happened yet than because disruption has been sold as advice, and because much that happened between 1997 and 2011 looks, in retrospect, disruptive. Disruptive innovation can reliably be seen only after the fact. History speaks loudly, apparently, only when you can make it say what you want it to say. The popular incarnation of the theory tends to disavow history altogether. ‘Predicting the future based on the past is like betting on a football team simply because it won the Super Bowl a decade ago,’ Josh Linkner writes in The Road to Reinvention. His first principle: ‘Let go of the past.’ It has nothing to tell you. But, unless you already believe in disruption, many of the successes that have been labelled disruptive innovation look like something else, and many of the failures that are often seen to have resulted from failing to embrace disruptive innovation look like bad management.

Christensen has compared the theory of disruptive innovation to a theory of nature: the theory of evolution. But among the many differences between disruption and evolution is that the advocates of disruption have an affinity for circular arguments. If an established company doesn’t disrupt, it will fail, and if it fails it must be because it didn’t disrupt. When a startup fails, that’s a success, since epidemic failure is a hallmark of disruptive innovation.”

Tags: Alan Shugart, Clayton M. Christensen, Jill Lepore, Josh Linkner

From the always fun Delanceyplace, a description of Japan’s initially bumpy entry into the American auto market in the 1950s, from Daniel Yergin’s The Quest:

“An odd and unfamiliar car might have been seen fleetingly on the streets of Los Angeles and San Francisco in the late 1950s. It was Toyota’s Toyopet S30 Crown, the first Japanese car to be brought officially to the United States. In Tokyo, Toyopets were used as taxis. But in the United States the Toyopet did not get off to a good start; the first two could not even get over the hills around Los Angeles. It is said that the first car delivered in San Francisco died on the first hill it encountered on the way to inspection. An auto dealer in that city drove it 180 times in reverse around the public library in an effort to promote it, but to no avail. The Toyopet, priced at $1,999, was anything but a hit. Over a four-year period, a total of 1,913 were sold. Other Japanese automakers also started exporting to the United States, but the numbers sold remained exceedingly modest, and the cars themselves were regarded as cheap, not very reliable, oddballs, and starter cars (lacking the vim and panache of what was then the hot import, the Volkswagen Beetle).”

Tags: Daniel Yergin

From “Reading in a Connected Age,” Neil Levy’s Practical Ethics post which argues that the surfeit of information on the Internet isn’t ending literacy but actually changing it in a necessary way:

“Here I want to consider one potential negative effect of the internet. In a recent blog post, Tim Parks argues that the constant availability of the temptations of the internet has led to a decline in the capacity to focus for long periods, and therefore in the capacity to consume big serious books. Big serious books are still written and read, he notes, but ‘the texture of these books seems radically different from the serious fiction of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries,’ Their prose has a ‘battering ram quality,’ which enables readers to consume them through frequent interruptions.

But of course one would expect – fervently hope – that books written in the 21st century are radically different from those written 100 years ago. After all, if you want to read Dickens and Dostoevsky and the like, there is plentiful quality literature from that period surviving: why would a contemporary writer add to those stocks? Its worth noting, as Francesca Segal points out, that Dickens’ own work was originally published in serial form: that is, in the bite-size chunks that Parks think characterise the contemporary novel in an age of reduced concentration spans.

Perhaps there is something to Parks’ hypothesis that the way the novel has changed reflects changes in the capacities of contemporary readers, but making that claim is going to take careful study. You can’t make it from the armchair. Without proper data and proper controls, we are vulnerable to the confirmation bias, where we attend to evidence that supports our hypothesis and overlook evidence that doesn’t, and many other biases that make these kinds of anecdotal reports useless as evidence.

Here is what may be happening to Parks. He is finding himself aware of a loss of focus more than he used to be. But is that evidence that he is actually losing focus more often than previously?”

Tags: Neil Levy

Daniel Keyes, the brain-centric novelist who wrote Flowers for Algernon, just passed away. I would suppose the story will take on even greater resonance as we move closer to genuine cognitive enhancement. The origin story behind his most famous novel, from Daniel E. Slotnik in the New York Times:

“The premise underlying Mr. Keyes’s best-known novel struck him while he waited for an elevated train to take him from Brooklyn to New York University in 1945.

‘I thought: My education is driving a wedge between me and the people I love,’ he wrote in his memoir, Algernon, Charlie and I (1999). ‘And then I wondered: What would happen if it were possible to increase a person’s intelligence?’

After 15 years that thought grew into the novella Flowers for Algernon, which was published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1959 and won the Hugo Award for best short fiction in 1960.

By 1966 Mr. Keyes had expanded the story into a novel with the same title, which tied for the Nebula Award for best novel that year. The film, for which Mr. Robertson won the Academy Award for best actor, was released in 1968.

Flowers for Algernon went on to sell more than five million copies and to become a staple of English classes.”

Tags: Daniel E. Slotnik, Daniel Keyes

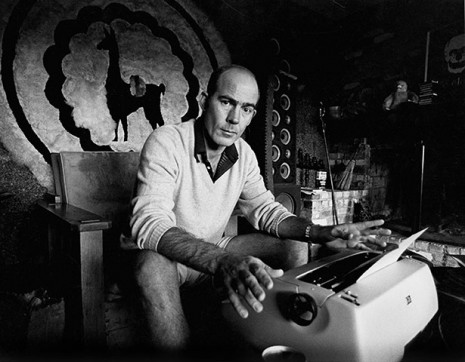

A passage from one of the most infamous TV interviews ever, Stanley Siegel questioning a seriously inebriated Truman Capote in 1978, a time before the commodification of dysfunction was prevalent.

Tags: Stanley Siegel, Truman Capote

In 1990, during the mercifully short-lived Deborah Norville era of the Today Show, Michael Crichton stops by to discuss his just-published novel, Jurassic Park.

Tags: Deborah Norville, Michael Crichton

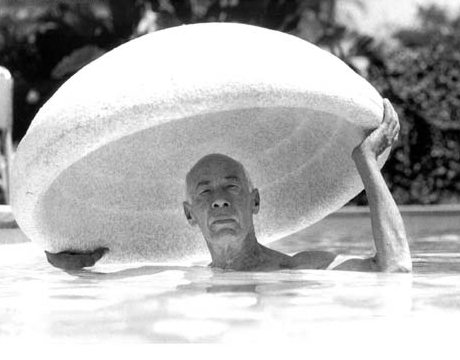

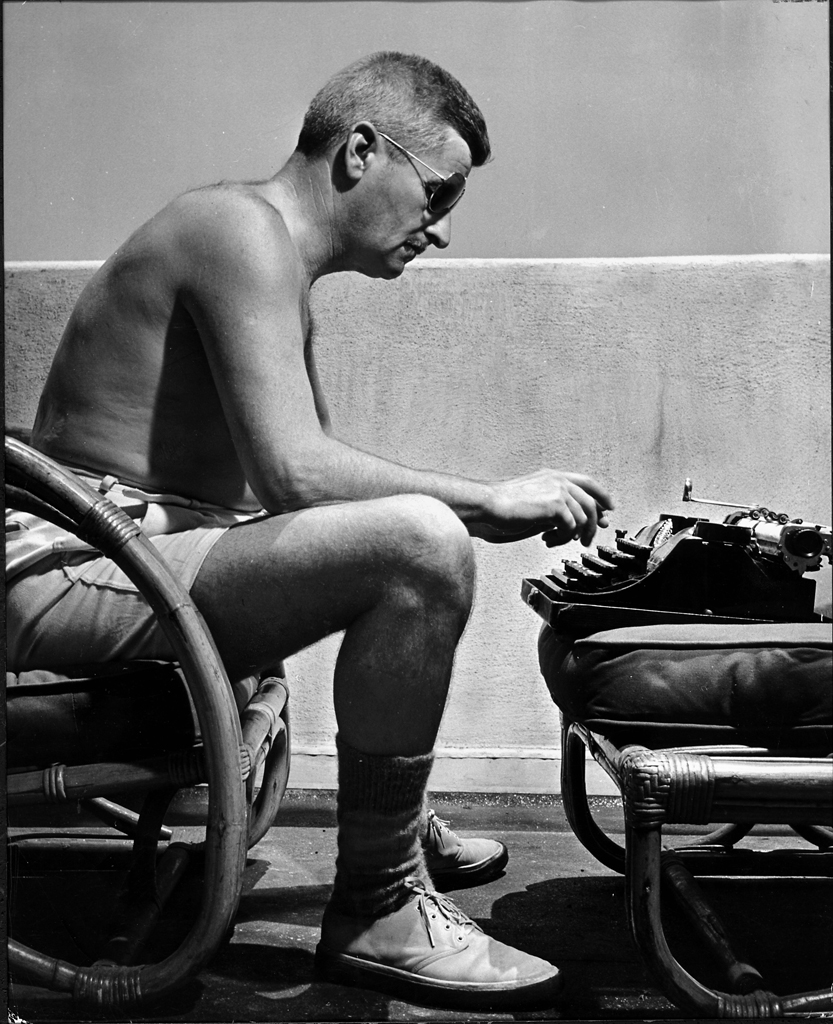

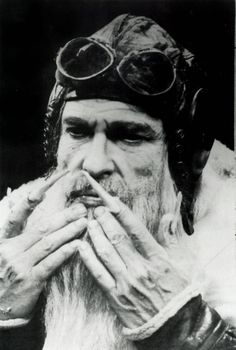

A piece of Henry Miller’s final interview, shortly before his death in 1980.

People aren’t so drawn to Miller because they agree with everything he wrote or did, but because he refused to accept the things handed him that made him unhappy in a time when it was very difficult to say “no.” That’s best expressed in the opening of The Tropic of Capricorn:

“Once you have given up the ghost, everything follows with dead certainty, even in the midst of chaos. From the beginning it was never anything but chaos: it was a fluid which enveloped me, which I breathed in through the gills. In the substrata, where the moon shone steady and opaque, it was smooth and fecundating; above it was a jangle and a discord. In everything I quickly saw the opposite, the contradiction, and between the real and the unreal the irony, the paradox. I was my own worst enemy. There was nothing I wished to do which I could just as well not do. Even as a child, when I lacked for nothing, I wanted to die: I wanted to surrender because I saw no sense in struggling. I felt that nothing would be proved, substantiated, added or subtracted by continuing an existence which I had not asked for. Everybody around me was a failure, or if not a failure, ridiculous. Especially the successful ones. The successful ones bored me to tears. I was sympathetic to a fault, but it was not sympathy that made me so. It was purely negative quality, a weakness which blossomed at the mere sight of human misery. I never helped anyone expecting that it would do me any good; I helped because I was helpless to do otherwise. To want to change the condition of affairs seemed futile to me; nothing would be altered, I was convinced, except by a change of heart, and who could change the hearts of men? Now and then a friend was converted: it was something to make me puke. I had no more need of God than He had of me, and if there were one, I often said to myself, I would meet Him calmly and spit in His face.

What was most annoying was that at first blush people usually took me to be good, to be kind, generous, loyal, faithful. Perhaps I did possess these virtues, but if so it was because I was indifferent: I could afford to be good, kind, generous, loyal, and so forth, since I was free of envy. Envy was the one thing I was never a victim of. I have never envied anybody or anything. On the contrary, I have only felt pity for everybody and everything.

From the very beginning I must have trained myself not to want anything too badly. From the very beginning I was independent, in a false way. I had need of nobody because I wanted to be free, free to do and to give only as my whims dictated. The moment anything was expected or demanded of me I balked. That was the form my independence took. I was corrupt, in other words, corrupt from the start. It’s as though my mother fed me a poison, and though I was weaned young the poison never left my system. Even when she weaned me it seemed that I was completely indifferent; most children rebel, or make a pretence of rebelling, but I didn’t give a damn. I was a philosopher when still in swaddling clothes. I was against life, on principle. What principle? The principle of futility. Everybody around me was struggling. I myself never made an effort. If I appeared to be making an effort it was only to please someone else; at bottom I didn’t give a rap. And if you can tell me why this should have been so I will deny it, because I was born with a cussed streak in me and nothing can eliminate it. I heard later, when I had grown up, that they had a hell of a time bringing me out of the womb. I can understand that perfectly. Why budge? Why come out of a nice warm place, a cosy retreat in which everything is offered you gratis? The earliest remembrance I have is of the cold, the snow and ice in the gutter, the frost on the window panes, the chill of the sweaty green walls in the kitchen. Why do people live in outlandish climates in the temperate zones, as they are miscalled? Because people are naturally idiots, naturally sluggards, naturally cowards. Until I was about ten years old I never realized that there were “warm” countries, places where you didn’t have to sweat for a living, nor shiver and pretend that it was tonic and exhilarating. Wherever there is cold there are people who work themselves to the bone and when they produce young they preach to the young the gospel of work – which is nothing, at bottom, but the doctrine of inertia. My people were entirely Nordic, which is to say idiots. Every wrong idea which has ever been expounded was theirs. Among them was the doctrine of cleanliness, to say nothing of righteousness. They were painfully clean. But inwardly they stank. Never once had they opened the door which leads to the soul; never once did they dream of taking a blind leap into the dark. After dinner the dishes were promptly washed and put in the closet; after the paper was read it was neatly folded and laid away on a shelf; after the clothes were washed they were ironed and folded and then tucked away in the drawers. Everything was for tomorrow, but tomorrow never came. The present was only a bridge and on this bridge they are still groaning, as the world groans, and not one idiot ever thinks of blowing up the bridge.”

Tags: Henry Miller

Some will always leave the culture, go off by themselves or in pairs or groups. They’ll disappear into their own heads, create their own reality. For most it’s benign, but not for all. There are those who don’t want to live parallel to the larger society and come to believe they can end it. The deeper they retreat, the harder it is to reemerge. Instead they sometimes explode back into their former world, as in the case of Jerad and Amanda Miller committing acts of domestic terrorism in Las Vegas. It reminds me of a piece of reportage by Denis Johnson.

The writer was paranoid about both the government and the anti-government militia movement in 1990s America when he wrote the chilling article “The Militia in Me,” which appears in his non-fiction collection, Seek. The violence of Ruby Ridge and Waco and the horrific Oklahoma City bombing had shocked the nation into realizing the terror within, so Johnson traveled the U.S. and Canada to find out how and why militias had come to be. Three brief excerpts from the piece.

____________________

The people I talked with seemed to imply that the greatest threat to liberty came from a conspiracy, or several overlapping conspiracies, well known to everybody but me. As a framework for thought, this has its advantages. It’s quicker to call a thing a crime and ask Who did it? than to call it a failure and set about answering the question What happened?

____________________

I’m one among many, part of a disparate–sometimes better spelled “desperate”–people, self-centered, shortsighted, stubborn, sentimental, richer than anybody’s ever been, trying to get along in the most cataclysmic century in human history. Many of us are troubled that somewhere, somehow, the system meant to keep us free has experienced a failure. A few believe that someone has committed the crime of sabotaging everything.

Failures need correction. Crimes cry out for punishment. Some ask: How do we fix it? Others: Who do we kill?

____________________

They told me they made furniture out of antlers and drove around anywhere and everywhere, selling it. For the past month I’d been reading about the old days, missing them as if I had lived in them, and I said, “You sound like free Americans.”

“No,” the smaller man said and thereafter did all the talking, while the other, the blond driver changed my tire. “No American is free today.”

“Okay, I guess you’re right, but what do we do about that?”

“We fight till we are,” he said. “Till we’re free or we’re dead, one or the other.”

“Who’s going to do the fighting?”

“A whole lot of men. More than you’d imagine. We’ll fight till we’re dead or we’re free.”•

Tags: Amanda Miller, Jerad Miller

Two brief excerpts from “Writing in the 21st Century,” a thought-provoking Edge piece about the nature of composition by Steven Pinker.

___________________

“The first thing you should think about is the stance that you as a writer take when putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. Writing is cognitively unnatural. In ordinary conversation, we’ve got another person across from us. We can monitor the other person’s facial expressions: Do they furrow their brow, or widen their eyes? We can respond when they break in and interrupt us. And unless you’re addressing a stranger you know the hearer’s background: whether they’re an adult or child, whether they’re an expert in your field or not. When you’re writing you have none of those advantages. You’re casting your bread onto the waters, hoping that this invisible and unknowable audience will catch your drift.

The first thing to do in writing well—before worrying about split infinitives—is what kind of situation you imagine yourself to be in. What are you simulating when you write, and you’re only pretending to use language in the ordinary way? That stance is the main thing that iw distinguishes clear vigorous writing from the mush we see in academese and medicalese and bureaucratese and corporatese.”

___________________

“Poets and novelists often have a better feel for the language than the self-appointed guardians and the pop grammarians because for them language is a medium. It’s a way of conveying ideas and moods with sounds. The most gifted writers—the Virginia Woolfs and H.G. Wellses and George Bernard Shaws and Herman Melvilles—routinely used words and constructions that the guardians insist are incorrect. And of course avant-garde writers such as Burroughs and Kerouac, and poets pushing the envelope or expanding the expressive possibilities of the language, will deliberately flout even the genuine rules that most people obey. But even non-avant garde writers, writers in the traditional canon, write in ways that would be condemned as grammatical errors by many of the purists, sticklers and mavens. “

Tags: Steven Pinker

Regardless of what actually killed him, Howard Hughes died of being Howard Hughes, eaten alive from the inside by neuroses. But that doesn’t mean he was alone at the feast. An autopsy suggested codeine and painkillers were among the culprits, and his personal physician, Dr. Wilbur Thain, whose brother-in-law Bill Gay was one of the executives angling for control of Hughes’ holdings, was treated like a precursor to Conrad Murray, though he was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing.

From Dennis Breo’s 1979 People interview with Thain, who made the extremely dubious assertion that aspirin abuse claimed the man who was both disproportionately rich and poor:

Question:

Are you satisfied that Hughes received adequate medical attention?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

Everything possible was done to help Hughes in his final hours. At no time did the authors of Empire try to get in touch with me. Yet they say in the book that an aviator friend of Hughes called me in Logan, Utah two days before Hughes’ death and told me, “I don’t want to play doctor, but your patient is dying.” I am quoted as telling the guy to mind his own business, since I had to go to a party in the Bahamas. Well, the first word I actually got that Hughes was in trouble was about 9 p.m. April 4, 1976—the night before he died. I was in Miami at the time—not Utah. At about midnight I was called and told that Hughes had suddenly become very critical. I was stunned. I left Miami at 3:30 a.m., arriving in Acapulco at 8 a.m. April 5.

Question:

What was the first thing you did?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

Empire says the first thing I did was spend two hours shredding documents in Hughes’ rooftop suite at the Acapulco Princess. This is absolutely false. I walked straight into Hughes’ bedroom with my medical bag. He was unconscious and having multiple seizures. He looked like he was about to die. Other than one trip to the bathroom, I spent the next four hours with him.

Question:

Why did you then fly to Houston?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

The Mexican physician who had seen Hughes advised against trying to take him to a local medical center, so we spent two hours trying to find an oxygen tank that didn’t leak and preparing the aircraft to fly us to Houston. We left at noon. He died en route.

Question:

Was Howard Hughes psychotic?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

No, not at any time in his life. He was severely neurotic, yes. To be psychotic means to be out of touch with reality. Howard Hughes may have had some fanciful ideas, but he was not out of touch with reality. He was rational until the day he died.

Question:

Was Hughes an impossible patient?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

That’s a masterpiece of understatement. He wanted doctors around, but he didn’t want to see them unless he had to. He would allow no X-rays—I never saw an X-ray of Hughes until after he died—no blood tests, no physical exams. He understood his situation and chose to live the way he lived. Rather than listen to a doctor, he would fall asleep or say he couldn’t hear.

Question:

Is that why you didn’t accept his job offer after you got out of medical school?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

No, I just wanted to practice medicine on my own. I understand that Hughes was quite upset. I didn’t see him again for 21 years. He was 67 then. He had grown a beard, his hair was longer. He had some hearing loss partially due to his work around aircraft. That’s why he liked to use the telephone: It had an amplifier. He was very alert and well-informed. His toenails and fingernails were pretty long, but he had a case of onchyomycosis—a fungus disease of the nails which makes them thick and very sensitive. It hurt like hell to trim them. For whatever reason, he only sponge-bathed his body and hair.

Question:

What was the turning point?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

After his successful hip surgery in August of 1973 he chose never to walk again. Once—only once—he walked from the bedroom to the bathroom with help. That was the beginning of the end for him. I told him we’d even get him a cute little physical therapist. He said, “No, Wilbur, I’m too old for that.”

Question:

Why did he decide not to walk?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

I never had the chance to pry off the top of his head to see what motivated decisions like this. He would never get his teeth fixed, either. Worst damn mouth I ever saw. When they operated on his hip, the surgeons were afraid his teeth were so loose that one would fall into his lung and kill him!

Question:

What kinds of things did he talk about toward the end of his life?

Dr. Wilbur Thain:

The last year we would talk about the Hughes Institute medical projects and his earlier life. All the reporting on Hughes portrayed him as a robot. This man had real feelings. He talked one day about his parents, whom he loved very much, and his movies and his girls. He said he finally gave up stashing women around Hollywood because he got tired of having to talk to them. In our last conversation, he told me how much he still loved his ex-wife Jean Peters. But he was also always talking about things 10 years down the road. He was an optimist in that sense. If it hadn’t been for the kidney failure, Hughes might have lasted a lot longer.•

A 1976 Houston local news report on the death of Howard Hughes, whose demise was as shrouded in mystery as was much of his life.

Tags: Dennis Breo, Howard Hughes, Wilbur Thain

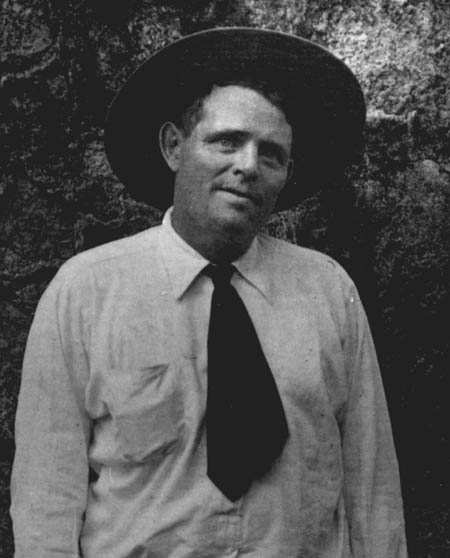

From a Modern Farmer article by Tyler LeBlanc about the last decade of Jack London’s life, when he repaired to Sonoma to create a “futuristic farm”:

Of his innovations, arguably the most impressive was the pig palace, an ultra-sanitary piggery that could house 200 hogs yet be operated by a single person. The palace gave each sow her own “apartment” complete with a sun porch and an outdoor area to exercise. The suites were built around a main feeding structure, while a central valve allowed the sole operator to fill every trough in the building with drinking water.

London wrote that he wanted the piggery to be “the delight of all pig-men in the United States.” While it may not have brought about significant change in the industry – it is said to have cost an astounding $3,000 (equal to $70,000 now) to build — it was one of London’s greatest innovations, and, unfortunately, his last. He died the following year.•

Tags: Jack London, Tyler LeBlanc

From Zoe Williams’ brief review of Ha-Joon Chang’s Economics: The User’s Guide, the first title from the revived Pelican paperback line, a description of the underlying forces that drive financial considerations:

“I think his favourite section is ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom’ – to judge, anyway, from his endearing pick’n’mix approach, in which he describes the nine key schools of thought, then makes up fresh labels, which you can use, if you wish, to describe yourself. The author’s references from culture proliferate: perhaps the best example is when he tries to explain, later, that the market isn’t logical, any more than is any other human behaviour, and that the things we can trade on the open market (carbon usage) and can’t (people, organs) come from beliefs, impulses and feelings that are deeper than money. ‘So politics is creating, shaping and reshaping markets before any transaction can begin. It is like the ‘Deeper Magic’ that had existed before the dawn of time, which is known to Aslan (the lion) but not to the White Witch in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.’“

Tags: Ha-Joon Chang, Zoe Williams

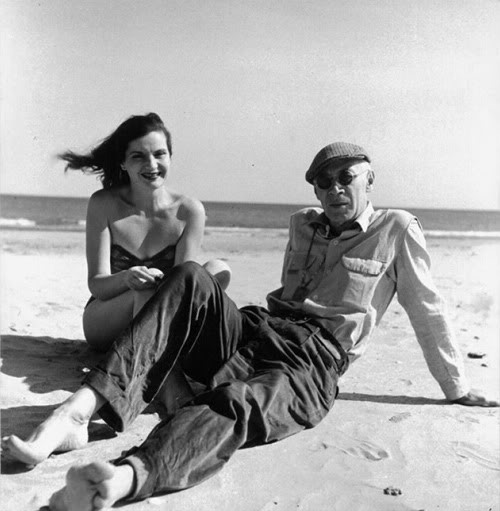

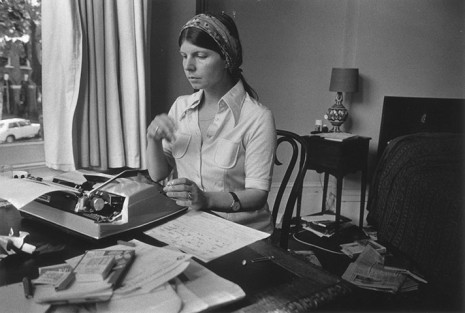

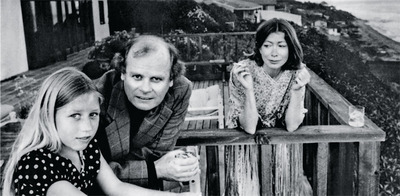

Joan Didion is one now, but when she was three her up-and-down marriage to fellow writer John Gregory Dunne was the topic of a 1976 People profile by John Riley. An excerpt:

Every morning Joan retreats to the Royal typewriter in her cluttered study, where she has finally finished her third novel, A Book of Common Prayer, due out early next year. John withdraws to his Olympia and his more fastidious office overlooking the ocean, where he’s most of the way through a novel called True Confessions. “At dinner she sits and talks about her book, and I talk about mine,” John says. “I think I’m her best editor, and I know she’s my best editor.”

While John played bachelor father to Quintana in Malibu, Joan spent a month in Sacramento—where she wrote the last 100 pages of the novel in her childhood bedroom in her parents’ home. She’s retreated there for the final month of all three novels. Her mother delivers breakfast at 9; her dad pours a drink at 6. The rest of the regimen: no one asks any questions about how she’s doing. Joan, a rare fifth-generation Californian, is the daughter of an Air Corps officer. She studied English at Berkeley and at 20 won a writing contest that led to an editing job with Vogue in New York. ‘All I could do during those days was talk long-distance to the boy I already knew I would never marry in the spring,’ she later wrote. John grew up in West Hartford, Conn., where his father was a surgeon. He prepped at a Catholic boarding school, Portsmouth Priory, and studied history at Princeton (where his classmates included Defense Secretary Don Rumsfeld and actor Wayne Rogers). After college he wrote for TIME.

He and Joan met in New York on opposite halves of a double date. When John’s girl passed out drunk in Didion’s apartment, she fixed him red beans and rice and, he recalls, “We talked all night.” Yet they remained only friends for six years until 1963, when they lunched to discuss the manuscript of her first novel, Run River. A year later they married.

California became home after Joan’s hypersensitivity pushed her to the brink of a crack-up in New York. ‘I cried in elevators and in taxis and in Chinese laundries,’ she recalls. “I could not work. I could not even get dinner with any degree of certainty.” Finally, in L.A., John and Joan began alternating columns in The Saturday Evening Post (they are presently sharing a his-and-hers column titled “The Coast” for Esquire). Soon they collaborated on their first filmscript, The Panic in Needle Park (which was co-produced by John’s brother Dominick). Her delicately wrought essays were collected in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, while John turned out nonfiction studies of the California grape workers’ strike (Delano) and 20th Century-Fox (The Studio).

They are only now emerging from two years of antisocial submersion in their novels. “This was the only time we’ve worked simultaneously on books,” John groans. “It was enormously difficult. There was no one to read the mail or serve as a pipeline to the outside world.” Finished ahead of John, Joan is baking bread, gardening and reestablishing contact with cronies like Gore Vidal and Katharine Ross. Unlike most serious writers, Joan and John have banked enough loot from the movies (they did script drafts for Such Good Friends and Play It As It Lays, among others) to indulge in two or three yearly trips to the Kahala Hilton in Hawaii. “Once you can accept the Hollywood mentality that says because you get $100,000 and the director gets $300,000, he’s three times smarter than you are, then it becomes a very amusing place to work,” John observes dryly. But, he adds: “If we didn’t have anything else, I think I’d slit my wrists.”

They’re currently dickering over two Hollywood projects, one about Alaska oil and another about California’s water-rights wars in the 1920s.•

Tags: Gore Vidal, Joan Didion, John Gregory Dunne, John Riley, Katharine Ross, Quintana Dunne

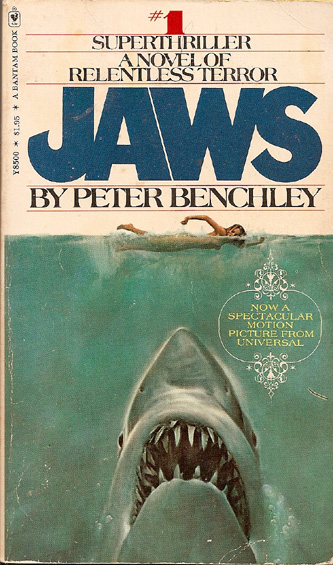

Here’s a rarity: Peter Benchley, author of Jaws, in a part of the preview featurette promoting the novel’s 1975 big-screen Spielberg adaptation, which changed so much about Hollywood filmmaking, pretty much creating the summer blockbuster season. The novelist interviews the director as well as producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown.

Tags: David Brown, Peter Benchley, Richard Zanuck, Steven Spielberg

I’m not on any social media even though I acknowledge there are a great many wonderful things about it. I just don’t know how healthy it is to live inside that machine. And that’s what it seems like to me–a machine. In fact, it probably most resembles a retro one, a pinball machine. The glass is transparent, there’s a lot of jarring noise and the likely outcomes are TILT and GAME OVER. At the end, you’re a little poorer and unnerved by the cheap titillation and the spent adrenaline. I think it’s particularly questionable whether we should be so linked to our past, that every day could be a high-school reunion. Sure, there’s comfort in it, but maybe comfort is what we want but not what we need. And, of course, being virtual isn’t being actual. Like an actor who goes too deeply into a role, it’s hard to disconnect ourselves from the unreality.

In stepping away for a spell from social media and his neverending Twitter wars, Patton Oswalt shared a quote he loves: “For fear of becoming dinosaurs we are turned into sheep.” It comes from Garret Keizer’s 2010 Harper’s essay, “Why Dogs Go After Mail Carriers.” Here’s the fuller passage from the piece:

“More than the unionization of its carriers or the federal oversight of its operations, the most bemoaned evil of the US mail is its slowness {1}. No surprise there, given our culture’s worship of speed. I would guess that when the average American hears the word socialism the first image to appear in his or her mind is that of a slow-moving queue, like they have down in Cuba, where people have been known to take a whole morning just to buy a chicken and a whole night just to make love. Unfortunately, the costs of our haste do not admit to hasty calculation. As Eva Hoffman notes in her 2009 book Time, ‘New levels of speed … are altering both our inner and outer worlds in ways we have yet to grasp, or fully understand.’

The influence of speed upon what Hoffman aptly calls ‘the very character and materiality of lived time’ [my emphasis] has been a topic of discussion for decades now, though its bourgeois construction typically leans toward issues of personal health and lifestyle aesthetics. Speed alters our brain chemistry; it leaves us too little time to smell the roses – a favorite trope among those who would do better to smell their own exhaust. In essence, the speed of a capitalistic society is about leaving others behind, the losers in the race, the ‘pedestrians’ at the side of the road, the people with obsolete computers and junker cars and slow-yield investments. An obsession with speed is also the fear of being left behind oneself – which drives the compulsion to buy the new car, the faster laptop, the inflated stock. For fear of becoming dinosaurs we are turned into sheep.'”

Tags: Eva Hoffman, Garret Keizer, Patton Oswalt

I don’t always agree with Malcolm Gladwell, but I always enjoy reading him for his ideas and because he’s a miraculously lucid writer. He just did an Ask Me Anything at Reddit. A few exchanges follow.

____________________________

Question:

Tags: Malcolm Gladwell, Peter Thiel, Steve Jobs

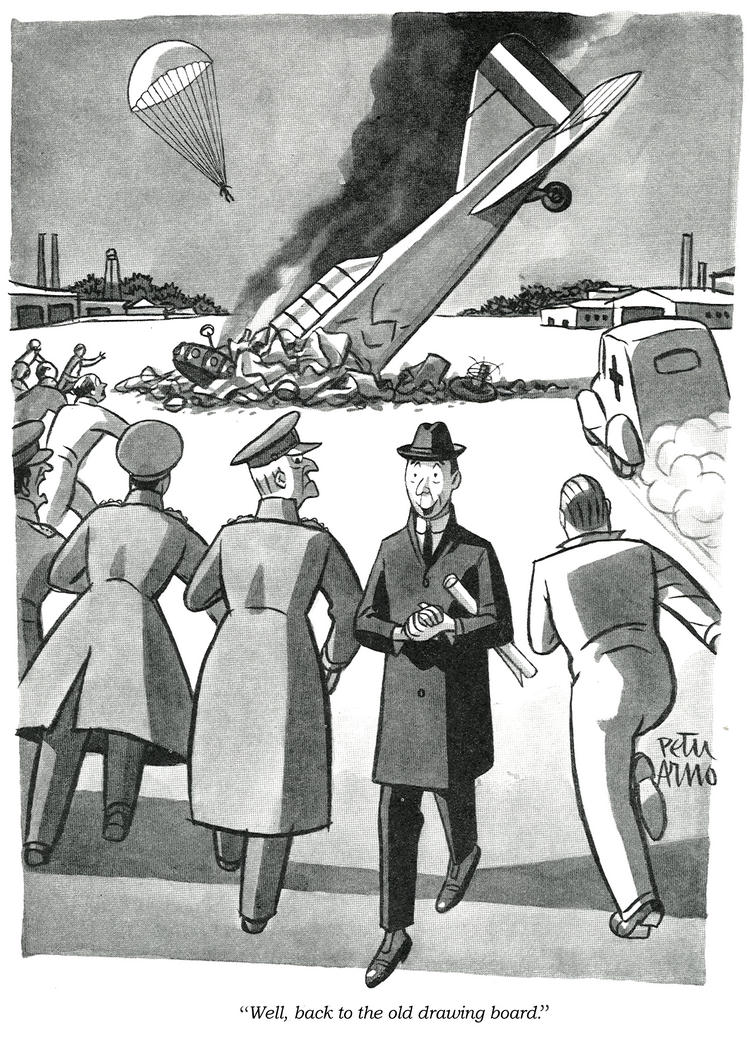

One of the quiet losses as print magazines have declined because of technological shifts and because they’ve been focus-grouped to death, is the dwindling of panel cartooning. From Bruce Handy’s New York Times Book Review piece about New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff’s just-published memoir:

“I should note, as Mankoff does, that The New Yorker didn’t invent the captioned, single-panel cartoon, but under the magazine’s auspices the form was modernized and perfected; [Peter] Arno, for one, ought to be as celebrated as Picasso and Matisse, or at least Ernst Lubitsch. But if The New Yorker has long been the pinnacle, ‘the Everest of magazine cartooning,’ as Mankoff puts it, the surrounding landscape has become more of a game preserve, with a sad, thinned herd of outlets. In olden days, when rejected drawings could be pawned off on, among many others, The Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, Ladies’ Home Journal or National Lampoon, a young cartoonist could afford the years it might take to breach The New Yorker — Mankoff himself made some 2,000 total submissions before he sold his first drawing to the magazine, in 1977. Today there are probably more people alive who speak Gullah or know how to thatch a roof than there are first-rate panel cartoonists.”

Tags: Bob Mankoff, Bruce Handy, Peter Arno

From Martin Filler’s mixed critique at New York Review of Books of Nikil Saval’s Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace, a brief explanation of the origins of the open office, which wasn’t chiefly the result of egalitarian impulse but of economic necessity:

“This revolutionary concept emerged in Germany in the late 1950s as die Bürolandschaft (the office landscape). Although the Bürolandschaft approach was codified by the Quickborner Team (an office planning company based in the Hamburg suburb of Quickborn), the ideas it embodied arose spontaneously during Germany’s rapid postwar recovery. With so much of the defeated country in ruins, and a large part of what business facilities that did survive commandeered by the Allied occupation forces (for example, Hans Poelzig’s I.G. Farben building of 1928–1930 in Frankfurt, then Europe’s largest office structure, taken over in 1945 as the American military’s bureaucratic command post), inexpensive improvisatory retrofits had to suffice for renascent German businesses. (A good sense of what those postwar spaces looked like can be gathered from Arno Mathes’s set decoration for Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1979 film The Marriage of Maria Braun, which recreates freestanding office partitions embellished with trailing philodendron vines.)

Within little more than a decade of its inception, the open office was embraced by American business furniture manufacturers eager to sell not just individual chairs, desks, and filing cabinets, but fully integrated office systems. These modular units incorporated partitions with ‘task’ lighting for up-close illumination, power conduits for the growing number of electrical office machines, and other infrastructural elements that promised unprecedented cost savings as functional needs changed over time.”

Tags: Martin Filler, Nikil Saval

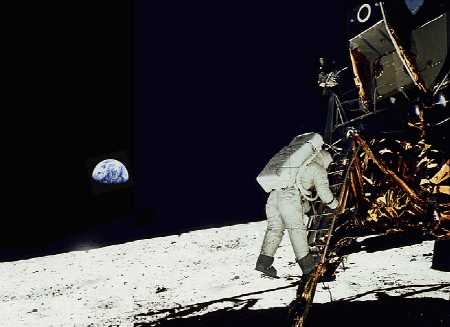

Norman Mailer pursued immortality through subjects as grand as his ego, and it was the Apollo 11 mission that was Moby Dick to his Ahab. He knew the beginning of space voyage was the end, in a sense, of humans, or, at least, of humans believing they were in the driver’s seat. Penguin Classics is republishing his great 1970 writing, Of a Fire on the Moon, 45 years after we touched down up there. Together with Oriana Fallaci’s If The Sun Dies, you have an amazing account of that disorienting moment when technology, that barbarian, truly stormed the gates, as well as a great look at New Journalism’s early peak. Below are some of the posts that I’ve previously put up that refer to Mailer’s book.

_________________________

“It Was Not A Despair He Felt, Or Fear–It Was Anesthesia”

When he wrote about the coming computer revolution of the 1970s at the outset of the decade in Of a Fire on the Moon, Norman Mailer couldn’t have known that the dropouts and the rebels would be leading the charge. An excerpt of his somewhat nightmarish view of our technological future, some parts of which came true and some still in the offing:

“Now they asked him what he thought of the Seventies. He did not know. He thought of the Seventies and a blank like the windowless walls of the computer city came over his vision. When he conducted interviews with himself on the subject it was not a despair he felt, or fear–it was anesthesia. He had no intimations of what was to come, and that was conceivably worse than any sentiment of dread, for a sense of the future, no matter how melancholy, was preferable to none–it spoke of some sense of the continuation in the projects of one’s life. He was adrift. If he tried to conceive of a likely perspective in the decade before him, he saw not one structure to society but two: if the social world did not break down into revolutions and counterrevolutions, into police and military rules of order with sabotage, guerrilla war and enclaves of resistance, if none of this occurred, then there certainly would be a society of reason, but its reason would be the logic of the computer. In that society, legally accepted drugs would become necessary for accelerated cerebration, there would be inchings toward nuclear installation, a monotony of architectures, a pollution of nature which would arouse technologies of decontamination odious as deodorants, and transplanted hearts monitored like spaceships–the patients might be obliged to live in a compound reminiscent of a Mission Control Center where technicians could monitor on consoles the beatings of a thousand transplanted hearts. But in the society of computer-logic, the atmosphere would obviously be plastic, air-conditioned, sealed in bubble-domes below the smog, a prelude to living on space stations. People would die in such societies like fish expiring on a vinyl floor. So of course there would be another society, an irrational society of dropouts, the saintly, the mad, the militant and the young. There the art of the absurd would reign in defiance against the computer.”

_________________________

Some more predictions from Norman Mailer’s 1970 Space Age reportage, Of a Fire on the Moon, which have come to fruition even without the aid of moon crystals:

“Thus the perspective of space factories returning the new imperialists of space a profit was now near to the reach of technology. Forget about diamonds! The value of crystals grown in space was incalculable: gravity would not be pulling on the crystal structure as it grew, so the molecule would line up in lattices free of shift or sheer. Such a perfect latticework would serve to carry messages for a perfect computer. Computers the size of a package of cigarettes would then be able to do the work of present computers the size of a trunk. So the mind could race ahead to see computers programming go-to-school routes in the nose of every kiddie car–the paranoid mind could see crystal transmitters sewn into the rump of ever juvenile delinquent–doubtless, everybody would be easier to monitor. Big Brother could get superseded by Moon Brother–the major monitor of them all might yet be sunk in a shaft on the back face of the lunar sphere.”

_________________________

In his 1970 Apollo 11 account, Of a Fire on the Moon, Norman Mailer realized that his rocket wasn’t the biggest after all, that the mission was a passing of the torch, that technology, an expression of the human mind, had diminished its creators. “Space travel proposed a future world of brains attached to wires,” Mailer wrote, his ego having suffered a TKO. And just as the Space Race ended the greater race began, the one between carbon and silicon, and it’s really just a matter of time before the pace grows too brisk for humans.

Supercomputers will ultimately be a threat to us, but we’re certainly doomed without them, so we have to navigate the future the best we can, even if it’s one not of our control. Gary Marcus addresses this and other issues in his latest New Yorker blog piece, “Why We Should Think About the Threat of Artificial Intelligence.” An excerpt:

“It’s likely that machines will be smarter than us before the end of the century—not just at chess or trivia questions but at just about everything, from mathematics and engineering to science and medicine. There might be a few jobs left for entertainers, writers, and other creative types, but computers will eventually be able to program themselves, absorb vast quantities of new information, and reason in ways that we carbon-based units can only dimly imagine. And they will be able to do it every second of every day, without sleep or coffee breaks.

For some people, that future is a wonderful thing. [Ray] Kurzweil has written about a rapturous singularity in which we merge with machines and upload our souls for immortality; Peter Diamandis has argued that advances in A.I. will be one key to ushering in a new era of ‘abundance,’ with enough food, water, and consumer gadgets for all. Skeptics like Eric Brynjolfsson and I have worried about the consequences of A.I. and robotics for employment. But even if you put aside the sort of worries about what super-advanced A.I. might do to the labor market, there’s another concern, too: that powerful A.I. might threaten us more directly, by battling us for resources.

Most people see that sort of fear as silly science-fiction drivel—the stuff of The Terminator and The Matrix. To the extent that we plan for our medium-term future, we worry about asteroids, the decline of fossil fuels, and global warming, not robots. But a dark new book by James Barrat, Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era, lays out a strong case for why we should be at least a little worried.

Barrat’s core argument, which he borrows from the A.I. researcher Steve Omohundro, is that the drive for self-preservation and resource acquisition may be inherent in all goal-driven systems of a certain degree of intelligence. In Omohundro’s words, ‘if it is smart enough, a robot that is designed to play chess might also want to build a spaceship,’ in order to obtain more resources for whatever goals it might have.”

_________________________

While Apollo 11 traveled to the moon and back in 1969, the astronauts were treated each day to a six-minute newscast from Mission Control about the happenings on Earth. Here’s one that was transcribed in Norman Mailer’s Of a Fire on the Moon, which made space travel seem quaint by comparison:

“Washington UPI: Vice President Spiro T. Agnew has called for putting a man on Mars by the year 2000, but Democratic leaders replied that priority must go to needs on earth…Immigration officials in Nuevo Laredo announced Wednesday that hippies will be refused tourist cards to enter Mexico unless they take a bath and get haircuts…’The greatest adventure in the history of humanity has started,’ declared the French newspaper Le Figaro, which devoted four pages to reports from Cape Kennedy and diagrams of the mission…Hempstead, New York: Joe Namath officially reported to the New York Jets training camp at Hofstra University Wednesday following a closed-door meeting with his teammates over his differences with Pro Football Commissioner Pete Rozelle…London UPI: The House of Lords was assured Wednesday that a major American submarine would not ‘damage or assault’ the Loch Ness monster.”

_________________________

“There Was An Uneasy Silence, An Embarrassed Pall At The Unmentioned Word Of Nazi”

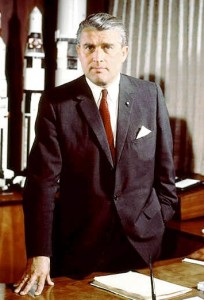

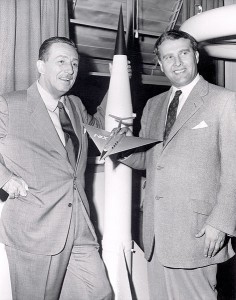

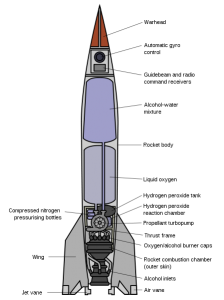

Norman Mailer’s book Of a Fire on the Moon, about American space exploration during the 1960s, was originally published as three long and personal articles for Life magazine in 1969: “A Fire on the Moon,” “The Psychology of Astronauts,” and “A Dream of the Future’s Face.” Mailer used space travel to examine America’s conflicted and tattered existence–and his own as well. In one segment, he reports on a banquet in which Wernher von Braun, the former Nazi rocket engineer who became a guiding light at NASA, meets with American businessmen on the eve of the Apollo 11 launch. An excerpt:

“Therefore, the audience was not to be at ease during his introduction, for the new speaker, who described himself as a ‘backup publisher,’ went into a little too much historical detail. ‘During the Thirties he was employed by the Ordinance Department of the German government developing liquid fuel rockets. During World War II he made very significant developments in rocketry for his government.’

A tension spread in this audience of corporation presidents and high executives, of astronauts, a few at any rate, and their families. There was an uneasy silence, an embarrassed pall at the unmentioned word of Nazi–it was the shoe which did not drop to the floor. So no more than a pitter-patter of clapping was aroused when the speaker went quickly on to say: ‘In 1955 he became an American citizen himself.’ It was only when Von Braun stood up at the end that the mood felt secure enough to shift. A particularly hearty and enthusiastic hand of applause swelled into a standing ovation. Nearly everybody stood up. Aquarius, who finally cast his vote by remaining seated, felt pressure not unrelated to refusing to stand up for The Star-Spangled Banner. It was as if the crowd with true American enthusiasm had finally declared, ‘Ah don’ care if he is some kind of ex-Nazi, he’s a good loyal patriotic American.’

Von Braun was. If patriotism is the ability to improve a nation’s morale, then Von Braun was a patriot. It was plain that some of these corporate executives loved him. In fact, they revered him. He was the high priest of their precise art–manufacture. If many too many an American product was accelerating into shoddy these years since the war, if planned obsolescence had all too often become a euphemism for sloppy workmanship, cynical cost-cutting, swollen advertising budgets, inefficiency and general indifference, then in one place at least, and for certain, America could be proud of a product. It was high as a castle and tooled more finely than the most exquisite watch.

Von Braun was. If patriotism is the ability to improve a nation’s morale, then Von Braun was a patriot. It was plain that some of these corporate executives loved him. In fact, they revered him. He was the high priest of their precise art–manufacture. If many too many an American product was accelerating into shoddy these years since the war, if planned obsolescence had all too often become a euphemism for sloppy workmanship, cynical cost-cutting, swollen advertising budgets, inefficiency and general indifference, then in one place at least, and for certain, America could be proud of a product. It was high as a castle and tooled more finely than the most exquisite watch.

Now the real and true tasty beef of capitalism got up to speak, the grease and guts of it, the veritable brawn, and spoke with fulsome language in his small and well-considered voice. He was with friends on this occasion, and so a savory and gravy of redolence came into his tone, his voice was not unmusical, it had overtones which hinted of angelic super-possibilities one could not otherwise lay on the line. He was when all was said like the head waiter of the largest hofbrau in heaven. ‘Honored guests, ladies and gentlemen,’ Von Braun began, ‘it is with a great deal of respect tonight that I meet you, the leaders, and the captains in the mainstream of American industry and life. Without your success in building and maintaining the economic foundations of this nation, the resources for mounting tomorrow’s expedition to the moon would never have been committed…. Tomorrow’s historic launch belongs to you and to the men and women who sit behind the desks and administer your companies’ activities, to the men who sweep the floor in your office buildings and to every American who walks the street of this productive land. It is an American triumph. Many times I have thanked God for allowing me to be a part of the history that will be made here today and tomorrow and in the next few days. Tonight I want to offer my gratitude to you and all Americans who have created the most fantastically progressive nation yet conceived and developed,’ He went on to talk of space as ‘the key to our future on earth,’ and echoes of his vision drifted through the stale tropical air of a banquet room after coffee–perhaps he was hinting at the discords and nihilism traveling in bands and brigands across the earth. ‘The key to our future on earth. I think we should see clearly from this statement that the Apollo 11 moon trip even from its inception was not intended as a one-time trip that would rest alone on the merits of a single journey. If our intention had been merely to bring back a handful of soil and rocks from the lunar gravel pit and then forget the whole thing’–he spoke almost with contempt of the meager resources of the moon–‘we would certainly be history’s biggest fools. But that is not our intention now–it never will be. What we are seeking in tomorrow’s trip is indeed that key to our future on earth. We are expanding the mind of man. We are extending this God-given brain and these God-given hands to their outermost limits and in so doing all mankind will benefit. All mankind will reap the harvest…. What we will have attained when Neil Armstrong steps down upon the moon is a completely new step in the evolution of man.'”

_________________________

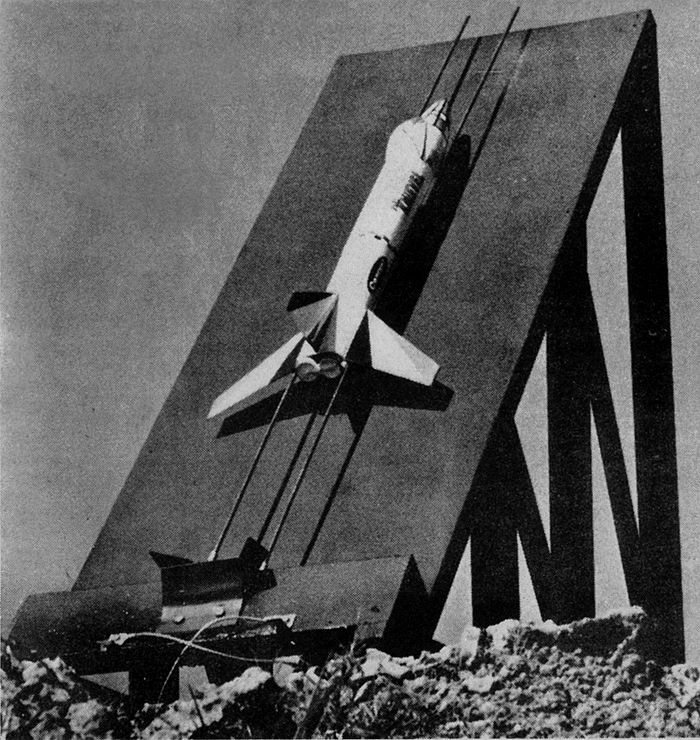

Wernher von Braun inducted into the Space Camp Hall of Fame:

Tom Lehrer eviscerates Wernher von Braun in under 90 seconds:

Tags: Norman Mailer

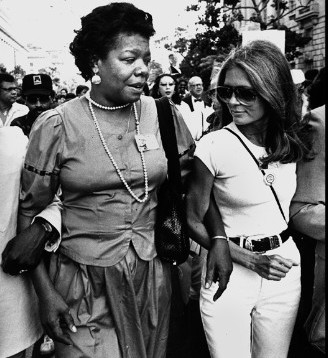

Maya Angelou, who sadly has just passed away, appearing with Merv Griffin in 1982, voicing her concerns about the beginning of what she believed was a politicized class war on less-fortunate Americans, of Reaganomics trying to undo the gains of the New Deal and the Great Society.

Tags: Maya Angelou, Merv Griffin, Ronald Reagan

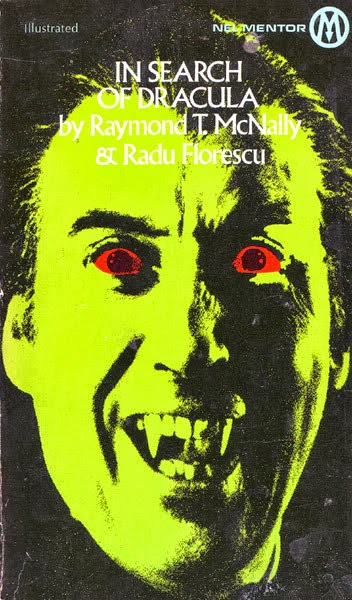

That excellent Margalit Fox at the New York Times penned a postmortem for a Romanian academic who became an unlikely literary superstar when his story intersected with that of one of the world’s most feared figures. An excerpt:

“The first of his many books on the subject, In Search of Dracula, published in 1972 and written with Raymond T. McNally, helped spur the revival of interest in Stoker’s vampirical nobleman that continues to this day.

‘It has changed my life,’ Professor Florescu told The New York Times in 1975. ‘I used to write books that nobody read.’

Radu Nicolae Florescu was born in Bucharest on Oct. 23, 1925. As he would learn in the course of his research, he had a family connection to Vlad, who was known familiarly if not quite fondly as Vlad Tepes, or Vlad the Impaler: A Florescu ancestor was said to have married Vlad’s brother, felicitously named Radu the Handsome.

At 13, as war loomed, Radu left home for London, where his father was serving as Romania’s acting ambassador to Britain. (The elder Mr. Florescu resigned his post after the dictator Ion Antonescu, a Nazi ally, became Romania’s prime minister in 1940.)

The younger Mr. Florescu earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in politics, philosophy and economics from Oxford, followed by a Ph.D. in history from Indiana University. He joined the Boston College faculty in 1953.

In the late 1960s, Professor McNally, a colleague in the history department, grew intrigued by affinities between events in Stoker’s novel, published in 1897, and the actual history of the region. He enlisted Professor Florescu, and together they scoured archives throughout Eastern Europe in an attempt to trace Count Dracula to a flesh-and-blood source.”

Michael Crichton pushed his book Electronic Life: How To Think About Computers while visiting Merv Griffin in 1983. The personal computing revolution was upon us, but the Macintosh had yet to reach the market, so it still seemed so far away, especially to the tech-challenged host.