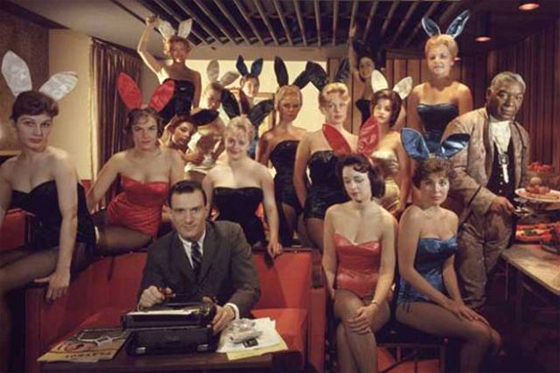

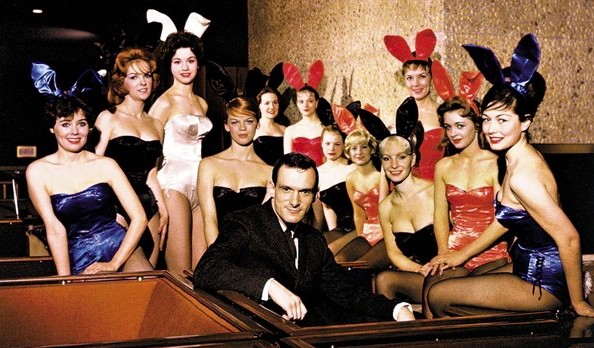

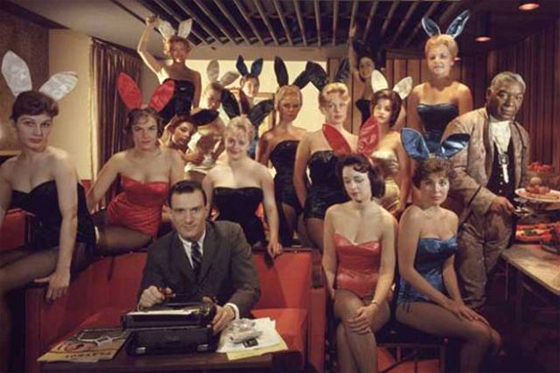

First of all, the House. He stays in it as a Pharaoh in a grave, and so he doesn’t notice that the night has ended, the day has begun, a winter passed, and a spring, and a summer–it’s autumn now. Last time he emerged from the grave was last winter, they say, but he did not like what he saw and returned with great relief three days later. The sky was then extinguished behind the electronic gate, and he sat down again in his grave: 1349 North State Parkway, Chicago. But what a grave, boys! Ask those who live in the building next to it, with their windows opening onto the terrace on which the bunnies sunbathe, in monokinis or notkinis. (The monokini exists of panties only, the notkini consists of nothing.) Tom Wolfe has called the house the final rebellion against old Europe and its custom of wearing shoes and hats, its need of going to restaurants or swimming pools. Others have called it Disneyland for adults. Forty-eight rooms, thirty-six servants always at your call. Are you hungry? The kitchen offers any exotic food at any hour. Do you want to rest? Try the Gold Room, with a secret door you open by touching the petal of a flower, in which the naked girls are being photographed. Do you want to swim? The heated swimming pool is downstairs. Bathing suits of any size or color are here, but you can swim without, if you prefer. And if you go into the Underwater Bar, you will see the Bunnies swim as naked as little fishes. The House hosts thirty Bunnies, who may go everywhere, like members of the family. The pool also has a cascade. Going under the cascade, you arrive at the grotto, rather comfortable if you like to flirt; tropical plants, stereophonic music, drinks, erotic opportunities, and discreet people. Recently, a guest was imprisoned in the steam room. He screamed, but nobody came to help him. Finally, he was able to free himself by breaking down the door, and when he asked in anger, why nobody came to his help–hadn’t they heard his screams?–they answered, “Obviously. But we thought you were not alone.”

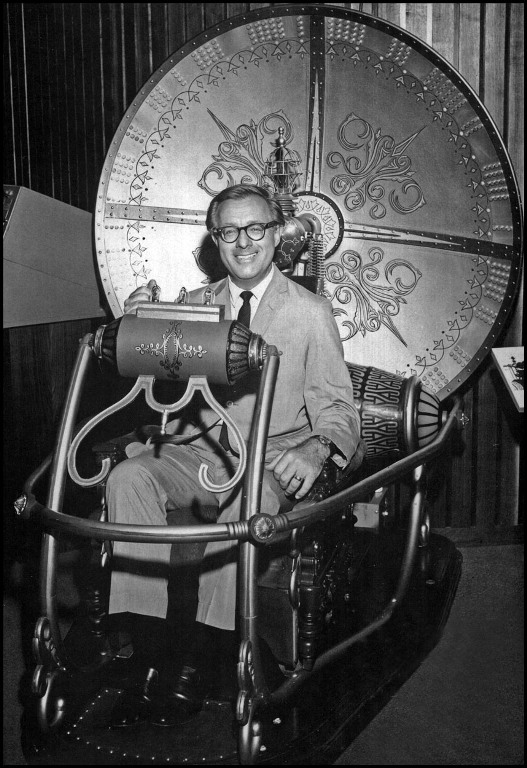

At the center of the grave, as at the center of a pyramid, is the monarch’s sarcophagus: his bed. It’s a large, round and here he sleeps, he thinks, he makes love, he controls the little cosmos that he has created, using all the wonders that are controlled by electronic technology. You press a button and the bed turns through half a circle, the room becomes many rooms, the statue near the fireplace becomes many statues. The statue portrays a woman, obviously. Naked, obviously. And on the wall there TV sets on which he can see the programs he missed while he slept or thought or made love. In the room next to the bedroom there is a laboratory with the Ampex video-tape machine that catches the sounds and images of all the channels; the technician who takes care of it was sent to the Ampex center in San Francisco. And then? Then there is another bedroom that is his office, because he does not feel at ease far from a bed. Here the bed is rectangular and covered with papers and photos and documentation on Prostitution, Heterosexuality, Sodomy. Other papers are on the floor, the chairs, the tables, along with tape recorders, typewriters, dictaphones. When he works, he always uses the electric light, never opening a window, never noticing the night has ended, the day begun. He wears pajamas only. In his pajamas, he works thirty-six hours, forty-eight hours nonstop, until he falls exhausted on the round bed, and the House whispers the news: He sleeps. Keep silent in the kitchen, in the swimming pool, in the lounge, everywhere: He sleeps.

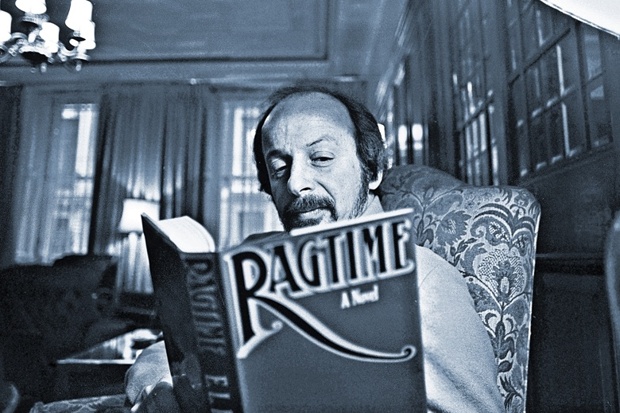

He is Hugh Hefner, emperor of an empire of sex, absolute king of seven hundred Bunnies, founder and editor of Playboy: forty million dollars in 1966, bosoms, navels, behinds as mammy made them, seen from afar, close up, white, suntanned, large, small, mixed with exquisite cartoons, excellent articles, much humor, some culture, and, finally, his philosophy. This philosophy’s name is “Playboyism,” and, synthesized, it says that “we must not be afraid or ashamed of sex, sex is not necessarily limited to marriage, sex is oxygen, mental health. Enough of virginity, hypocrisy, censorship, restrictions. Pleasure is to be preferred to sorrow.” It is now discussed even by theologians. Without being ironic, a magazine published a story entitled “…The Gospel According to Hugh Hefner.” Without causing a scandal, a teacher at the School of Theology at Claremont, California, writes that Playboyism is, in some ways, a religious movement: “That which the church has been too timid to try, Hugh Hefner…is attempting.”

We Europeans laugh. We learned to discuss sex some thousands of years ago, before even the Indians landed in America. The mammoths and the dinosaurs still pastured around New York, San Francisco, Chicago, when we built on sex the idea of beauty, the understanding of tragedy, that is our culture. We were born among the naked statues. And we never covered the source of life with panties. At the most, we put on it a few mischievous fig leaves. We learned in high school about a certain Epicurus, a certain Petronius, a certain Ovid. We studied at the university about a certain Aretino. What Hugh Hefner says does not make us hot or cold. And now we have Sweden. We are all going to become Swedish, and we do not understand these Americans, who, like adolescents, all of a sudden, have discovered that sex is good not only for procreating. But then why are half a million of the four million copies of the monthly Playboy sold in Europe? In Italy, Playboy can be received through the mail if the mail is not censored. And we must also consider all the good Italian husbands who drive to the Swiss border just to buy Playboy. And why are the Playboy Clubs so famous in Europe, why are the Bunnies so internationally desired? The first question you hear when you get back is: “Tell me, did you see the Bunnies? How are they? Do they…I mean…do they?!?” And the most severe satirical magazine in the U.S.S.R., Krokodil, shows much indulgence toward Hugh Hefner: “[His] imagination in indeed inexhaustible…The old problem of sex is treated freshly and originally…”

We Europeans laugh. We learned to discuss sex some thousands of years ago, before even the Indians landed in America. The mammoths and the dinosaurs still pastured around New York, San Francisco, Chicago, when we built on sex the idea of beauty, the understanding of tragedy, that is our culture. We were born among the naked statues. And we never covered the source of life with panties. At the most, we put on it a few mischievous fig leaves. We learned in high school about a certain Epicurus, a certain Petronius, a certain Ovid. We studied at the university about a certain Aretino. What Hugh Hefner says does not make us hot or cold. And now we have Sweden. We are all going to become Swedish, and we do not understand these Americans, who, like adolescents, all of a sudden, have discovered that sex is good not only for procreating. But then why are half a million of the four million copies of the monthly Playboy sold in Europe? In Italy, Playboy can be received through the mail if the mail is not censored. And we must also consider all the good Italian husbands who drive to the Swiss border just to buy Playboy. And why are the Playboy Clubs so famous in Europe, why are the Bunnies so internationally desired? The first question you hear when you get back is: “Tell me, did you see the Bunnies? How are they? Do they…I mean…do they?!?” And the most severe satirical magazine in the U.S.S.R., Krokodil, shows much indulgence toward Hugh Hefner: “[His] imagination in indeed inexhaustible…The old problem of sex is treated freshly and originally…”

Then let us listen with amusement to this sex lawmaker of the Space Age. He’s now in his early forties. Just short of six feet, he weighs one hundred and fifty pounds. He eats once a day. He gets his nourishment essentially from soft drinks. He does not drink coffee. He is not married. He was briefly, and he has a daughter and a son, both teen-agers. He also has a father, a mother, a brother. He is a tender relative, a nepotist: his father works for him, his brother, too. Both are serious people, I am informed.

And then I am informed that the Pharaoh has awakened, the Pharaoh is getting dressed, is going to arrive, has arrived: Hallelujah! Where is he? He is there: that young man, so slim, so pale, so consumed by the lack of light and the excess of love, with eyes so bright, so smart, so vaguely demoniac. In his right hand he holds a pipe: in his left hand he holds a girl, Mary, the special one. After him comes his brother, who resembles Hefner. He also holds a girl, who resembles Mary. I do not know if the pipe he owns resembles Hugh’s pipe because he is not holding one right now. It’s a Sunday afternoon, and, as on every Sunday afternoon, there is a movie in the grave. The Pharaoh lies down on the sofa with Mary, the light goes down, the movie starts. The Bunnies go to sleep and the four lovers kiss absentminded kisses. God knows what Hugh Hefner thinks about men, women, love, morals–will he be sincere in his nonconformity? What fun, boys, if I discover that he is a good, proper moral father of Family whose destiny is paradise. Keep silent, Bunnies. He speaks. The movie is over, and he speaks, with a soft voice that breaks. And, I am sure, without lying.

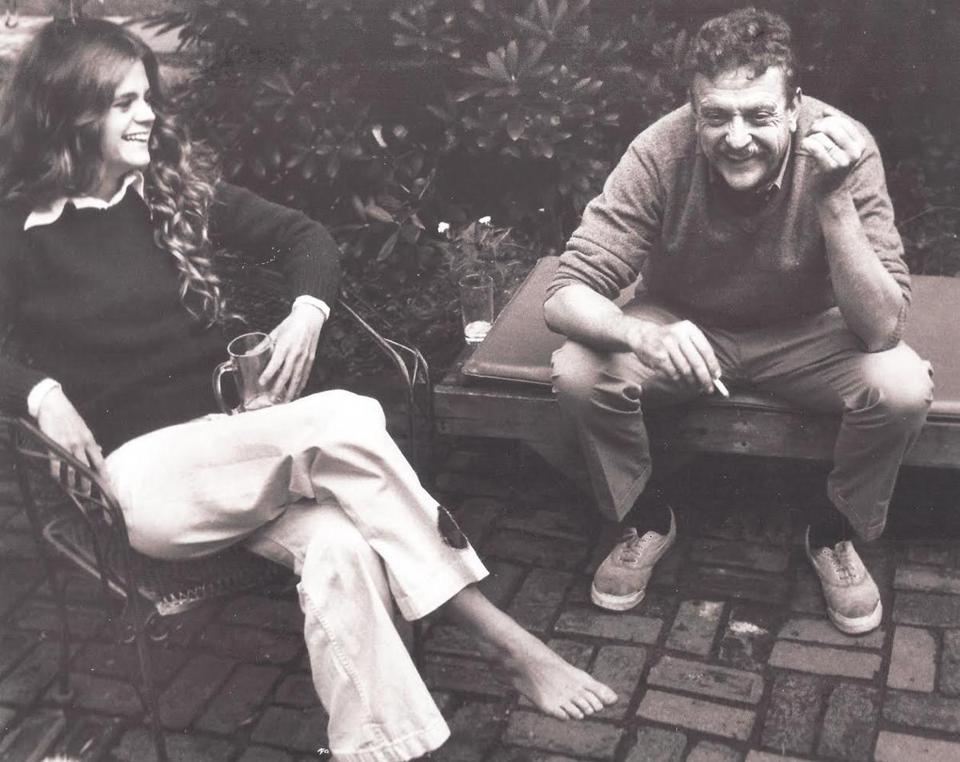

Oriana Fallaci:

A year without leaving the House, without seeing the sun, the snow, the rain, the trees, the sea, without breathing the air, do you not go crazy? Don’t you die with unhappiness?

Hugh Hefner:

Here I have all the air I need. I never liked to travel: the landscape never stimulated me. I am more interested in people and ideas. I find more ideas here than outside. I’m happy, totally happy. I go to bed when I like. I get up when I like: in the afternoon, at dawn, in the middle of the night. I am in the center of the world, and I don’t need to go out looking for the world. The rational use that I make of progress and technology brings me the world at home. What distinguishes men from other animals? Is it not perhaps their capacity to control the environment and to change it according to their necessities and tastes? Many people will soon live as I do. Soon, the house will be a little planet that does not prohibit but helps our relationships with the others. Is it not more logical to live as I do instead of going out of a little house to enter another little house, the car, then into another little house, the office, then another little house, the restaurant or the theater? Living as I do, I enjoy at the same time company and solitude, isolation from society and immediate access to society. Naturally, in order to afford such luxury, one must have money. But I have it. And it’s delightful.•

We Europeans laugh. We learned to discuss sex some thousands of years ago, before even the Indians landed in America. The mammoths and the dinosaurs still pastured around New York, San Francisco, Chicago, when we built on sex the idea of beauty, the understanding of tragedy, that is our culture. We were born among the naked statues. And we never covered the source of life with panties. At the most, we put on it a few mischievous fig leaves. We learned in high school about a certain Epicurus, a certain Petronius, a certain Ovid. We studied at the university about a certain Aretino. What Hugh Hefner says does not make us hot or cold. And now we have Sweden. We are all going to become Swedish, and we do not understand these Americans, who, like adolescents, all of a sudden, have discovered that sex is good not only for procreating. But then why are half a million of the four million copies of the monthly Playboy sold in Europe? In Italy, Playboy can be received through the mail if the mail is not censored. And we must also consider all the good Italian husbands who drive to the Swiss border just to buy Playboy. And why are the Playboy Clubs so famous in Europe, why are the Bunnies so internationally desired? The first question you hear when you get back is: “Tell me, did you see the Bunnies? How are they? Do they…I mean…do they?!?” And the most severe satirical magazine in the U.S.S.R., Krokodil, shows much indulgence toward Hugh Hefner: “[His] imagination in indeed inexhaustible…The old problem of sex is treated freshly and originally…”

We Europeans laugh. We learned to discuss sex some thousands of years ago, before even the Indians landed in America. The mammoths and the dinosaurs still pastured around New York, San Francisco, Chicago, when we built on sex the idea of beauty, the understanding of tragedy, that is our culture. We were born among the naked statues. And we never covered the source of life with panties. At the most, we put on it a few mischievous fig leaves. We learned in high school about a certain Epicurus, a certain Petronius, a certain Ovid. We studied at the university about a certain Aretino. What Hugh Hefner says does not make us hot or cold. And now we have Sweden. We are all going to become Swedish, and we do not understand these Americans, who, like adolescents, all of a sudden, have discovered that sex is good not only for procreating. But then why are half a million of the four million copies of the monthly Playboy sold in Europe? In Italy, Playboy can be received through the mail if the mail is not censored. And we must also consider all the good Italian husbands who drive to the Swiss border just to buy Playboy. And why are the Playboy Clubs so famous in Europe, why are the Bunnies so internationally desired? The first question you hear when you get back is: “Tell me, did you see the Bunnies? How are they? Do they…I mean…do they?!?” And the most severe satirical magazine in the U.S.S.R., Krokodil, shows much indulgence toward Hugh Hefner: “[His] imagination in indeed inexhaustible…The old problem of sex is treated freshly and originally…”