“If you do not know where you are going, any road will take you there.”

(Out of Confusion, by M.N. Chatterjee, Yellow Springs, Ohio: Antioch Press, 1954).

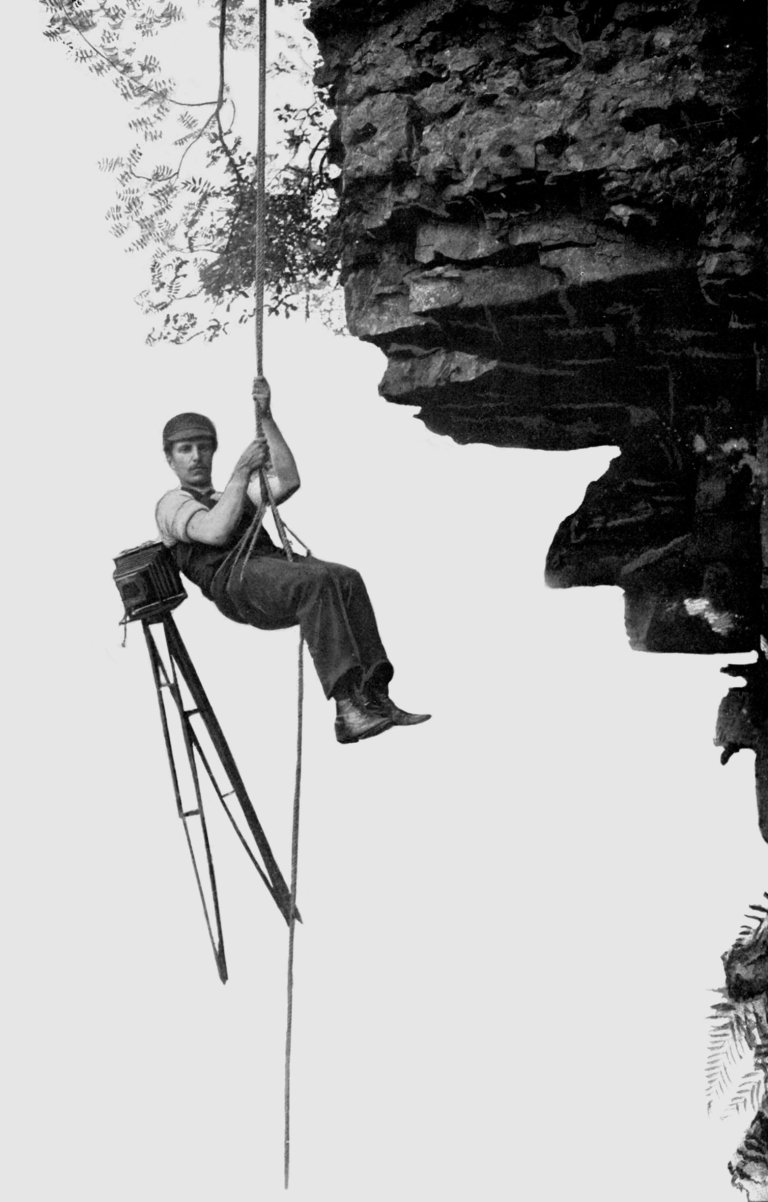

There are days when it all seems as simple and clear as that to me. What do I mean? I mean with regard to the problem of living on this earth without becoming a slave, a drudge, a hack, a misfit, an alcoholic, a drug addict, a neurotic, a schizophrenic, a glutton for punishment or an artist manqué.

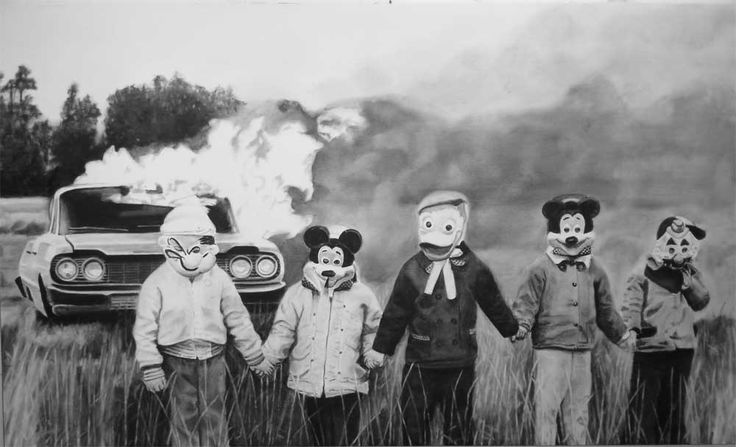

Supposedly we have the highest standard of living of any country in the world. Do we, though? It depends on what one means by high standards. Certainly nowhere does it cost more to live than here in America. The cost is not only in dollars and cents but in sweat and blood, in frustration, ennui, broken homes, smashed ideals, illness and insanity. We have the most wonderful hospitals, the most gorgeous insane asylums, the most fabulous prisons, the best equipped and the highest paid army and navy, the speediest bombers, the largest stockpile of atom bombs, yet never enough of any of these items to satisfy the demand. Our manual workers are the highest paid in the world; our poets the worst. There are more automobiles than one can count. And as for drugstores, where in the world will you find the like?

We have only one enemy we really fear: the microbe. But we are licking him on every front. True, millions still suffer from cancer, heart disease, schizophrenia, multiple-sclerosis, tuberculosis, epilepsy, colitis, cirrhosis of the liver, dermatitis, gall stones, neuritis, Bright’s disease, bursitis, Parkinson’s-disease, diabetes, floating kidneys, cerebral palsy, pernicious anaemia, encephalitis, locomotor ataxia, falling of the womb, muscular distrophy, jaundice, rheumatic fever, polio, sinus and antrum troubles, halitosis, St. Vitus’s Dance, narcolepsy, coryza, leucorrhea, nymphomania, phthisis, carcinoma, migraine, dipsomania, malignant tumors, high blood pressure, duodenal ulcers, prostate troubles, sciatica, goiter, catarrh, asthma, rickets, hepatitis, nephritis, melancholia, amoebic dysentery, bleeding piles, quinsy, hiccoughs, shingles, frigidity and impotency, even dandruff, and of course all the insanities, now legion, but–our of men of science will rectify all this within the next hundred years or so. How? Why, by destroying all the nasty germs which provoke this havoc and disruption! By waging a great preventive war–not a cold war!–wherein our poor, frail bodies will become a battleground for all the antibiotics yet to come. A game of hide and seek, so to speak, in which one germ pursues another, tracks it down and slays it, all without the least disturbance to our usual functioning. Until this victory is achieved, however, we may be obliged to continue swallowing twenty or thirty vitamins, all of different strengths and colors, before breakfast, down our tiger’s milk and brewer’s yeast, drink our orange and grapefruit juices, use blackstrap molasses on our oatmeal, smear our bread (made of stone-ground flour) with peanut butter, use raw honey or raw sugar with our coffee, poach our eggs rather than fry them, follow this with an extra glass of superfortified milk, belch and burp a little, give ourselves an injection, weigh ourselves to see if we are under or over, stand on our heads, do our setting-up exercises–if we haven’t done them already–yawn, stretch, empty the bowels, brush our teeth (if we have any left), say a prayer or two, then run like hell to catch the bus or the subway which will carry us to work, and think no more about the state of our health until we feel a cold coming on: the incurable coryza. But we are not to despair. Never despair! Just take more vitamins, add an extra dose of calcium and phosphorus pills, drink a hot toddy or two, take a high enema before retiring for the night, say another prayer, if we can remember one, and call it a day.

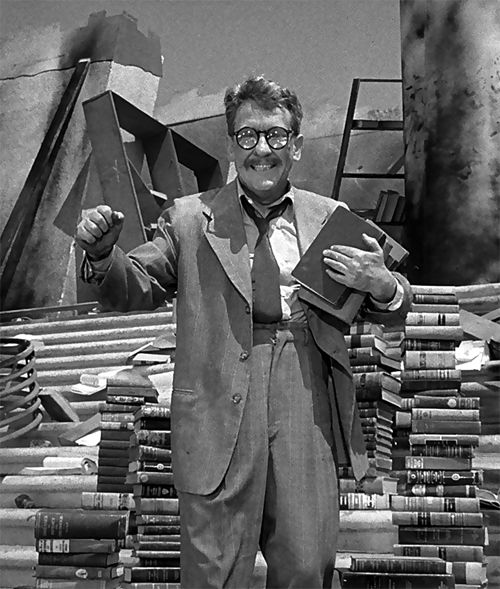

If the foregoing seems too complicated, here is a simple regimen to follow: Don’t overeat, don’t drink too much, don’t smoke too much, don’t work too much, don’t think too much, don’t fret, don’t worry, don’t complain, above all, don’t get irritable. Don’t use a car if you can walk to your destination; don’t walk if you can run; don’t listen to the radio or watch television; don’t read newspapers, magazines, digests, stock market reports, comics, mysteries or detective stories; don’t take sleeping pills or wakeup pills; don’t vote, don’t buy on the installment plan, don’t play cards either for recreation or to make a haul, don’t invest your money, don’t mortgage your home, don’t get vaccinated or inoculated, don’t violate the fish and game laws, don’t irritate your boss, don’t say yes when you mean no, don’t use bad language, don’t be brutal to your wife or children, don’t get frightened if you are over or under weight, don’t sleep more than ten hours at a stretch, don’t eat store bread if you can bake your own, don’t work at a job you loathe, don’t think the world is coming to an end because the wrong man got elected, don’t believe you are insane because you find yourself in a nut house, don’t do anything more than you’re asked to do but do that well, don’t try to help your neighbor until you’ve learned how to help yourself, and so on…

Simple, what?

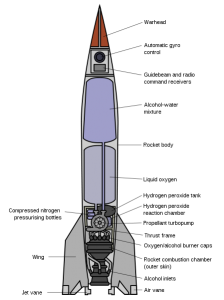

In short, don’t create aerial dinosaurs with which to frighten field mice!”

America has only one enemy, as I said before. The microbe. The trouble is, he goes under a million different names. Just when you think you’ve got him licked he pops up again in a new guise. He’s the pest personified.

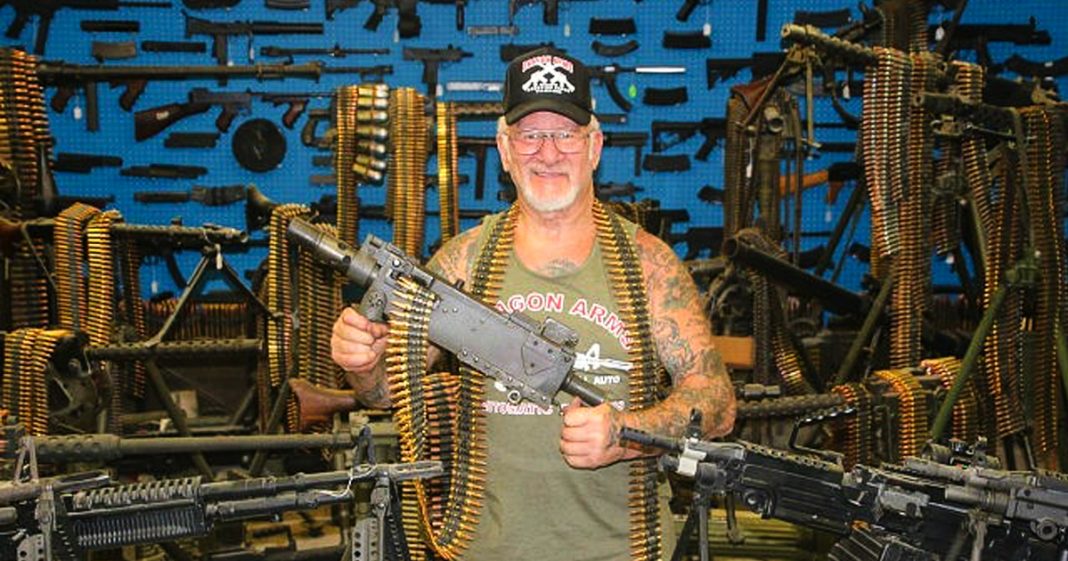

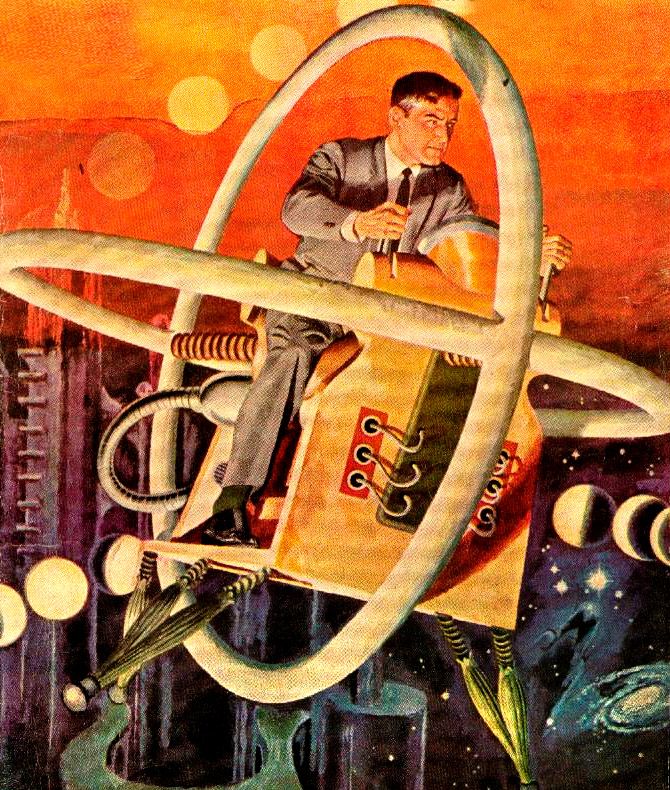

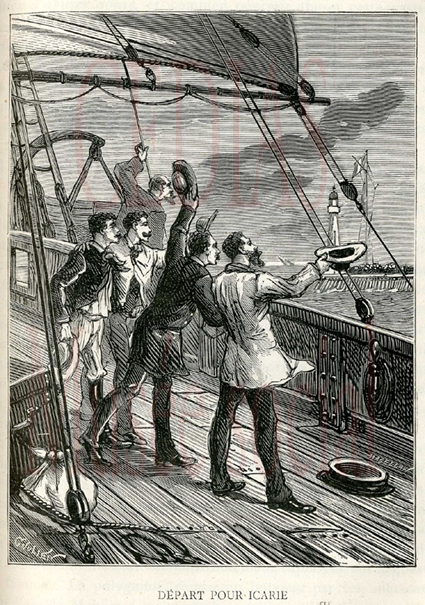

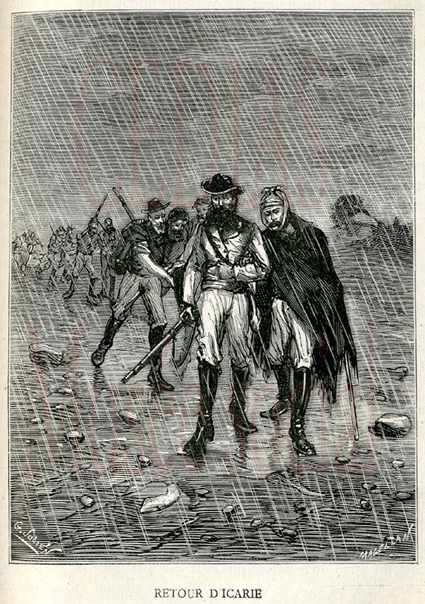

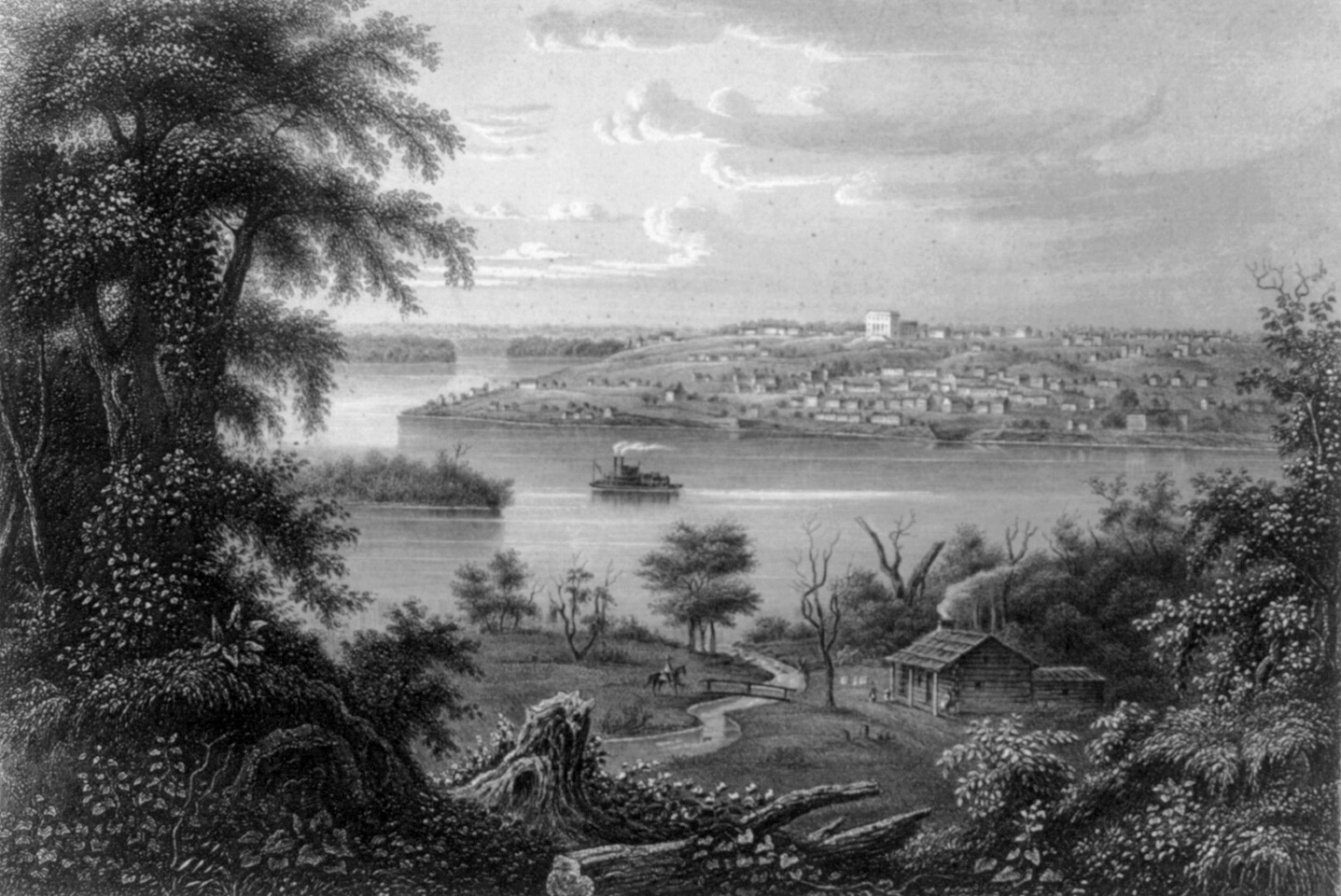

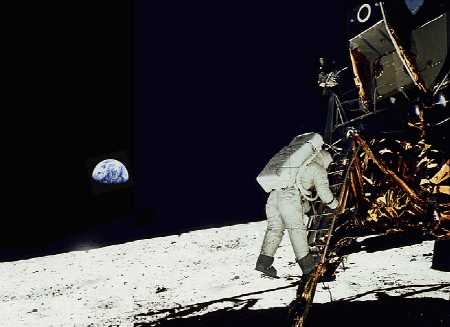

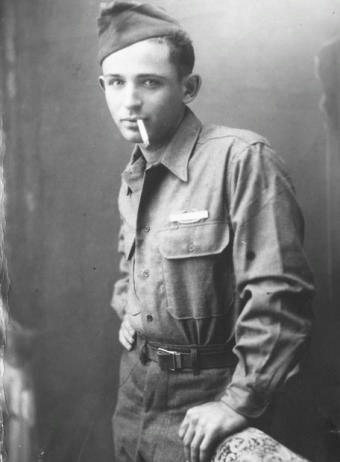

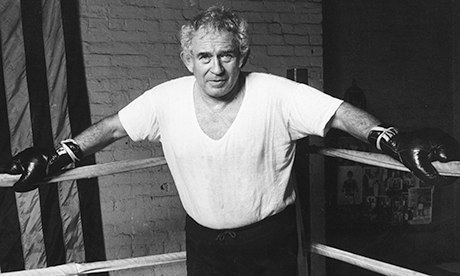

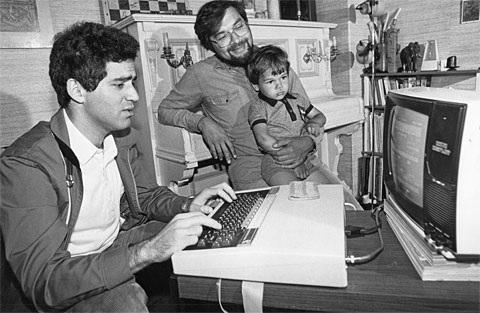

When we were a young nation life was crude and simple. Our great enemy then was the redskin. (He became our enemy when we took his land away from him.) In those early days there were no chain stores, no delivery lines, no hired purchase plan, no vitamins, no supersonic flying fortresses, no electronic computers; one could identify thugs and bandits easily because they looked different from other citizens. All one needed for protection was a musket in one hand and a Bible in the other. A dollar was a dollar, no more, no less. And a gold dollar, a silver dollar, was just as good as a paper dollar. Better than a check, in fact. Men like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett were genuine figures, maybe not so romantic as we imagine them today, but they were not screen heroes. The nation was expanding in all directions because there was a genuine need for it–we already had two or three million people and they needed elbow room. The Indians and bison were soon crowded out of the picture, along with a lot of other useless paraphernalia. Factories and mills were being built, and colleges and insane asylums. Things were humming. And then we freed the slaves. That made everybody happy, except the Southerners. It also made us realize that freedom is a precious thing. When we recovered from the loss of blood we began to think about freeing the rest of the world. To do it, we engaged in two world wars, not to mention a little war like the one with Spain, and now we’ve entered upon a cold war which our leaders warn us may last another forty or fifty years. We are almost at the point now where we may be able to exterminate every man, woman and child throughout the globe who is unwilling to accept the kind of freedom we advocate. It should be said, in extenuation, that when we have accomplished our purpose everybody will have enough to eat and drink, properly clothed, housed and entertained. An all-American program and no two ways about it! Our men of science will then be able to give their undivided attention to other problems, such as disease, insanity, excessive longevity, interplanetary voyages and the like. Everyone will be inoculated, not only against real ailments but against imaginary ones too. War will have been eliminated forever, thus making it unnecessary “in times of peace to prepare for war.” America will go on expanding, progressing, providing. We will plant the stars and stripes on the moon, and subsequently on all the planets within our comfy little universe. One world it will be, and American through and through. Strike up the band!•