Frederick R. Law, listed in the telephone directory as an aerial contractor, with offices at 50 Church Street, growing tired of monotonously swaying to and fro on lofty flagpoles and of being conventionally referred to in the newspapers as a daring steeplejack, decided yesterday to startle the world with an entirely original feat.

Law is about 35 years old. He was the first man to paint the flagpoles of the Pulitzer and Singer buildings, and it has been said of him that he had to be at least 300 feet in the air with a cigar in his mouth to feel absolutely comfortable. Business has been dull in the steeple rigging line, and Law saw the necessity of doing something which no one else had ever done before.

According to one of his foremen, the boss steeplejack sat in his office all yesterday morning looking over the city’s high towers. Suddenly, it was said, he announced his intention of jumping from the Singer Building with a parachute. That seemed unpractical, however, after an investigation, and the Metropolitan Tower, a few stories higher, offered the same objections. The steeplejack did not fear the jump, but impeding traffic and the risk of causing a runaway or two deterred him.

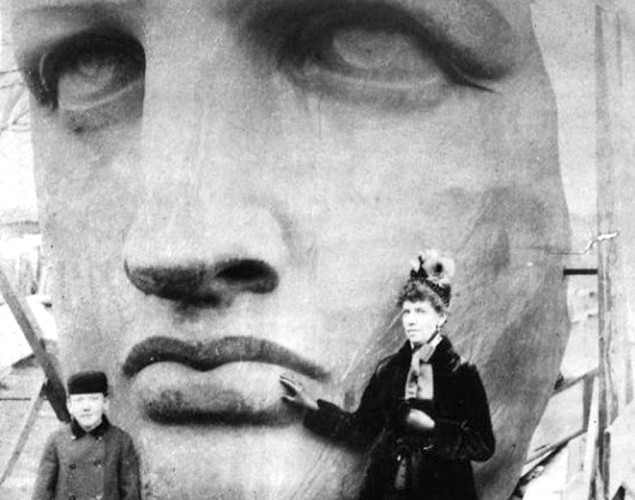

The happy alternative of the Statue of Liberty suggested itself, and at noon the aerial contractor set out for Bedlow’s Island. At 2 o’clock he was armed with a special permit, issued by Capt. Leonard D. Wildman in charge of the post on the island, and half an hour later half a dozen moving picture machines and operators and several thousand spectators were on hand to see the jump from the top of the statue.

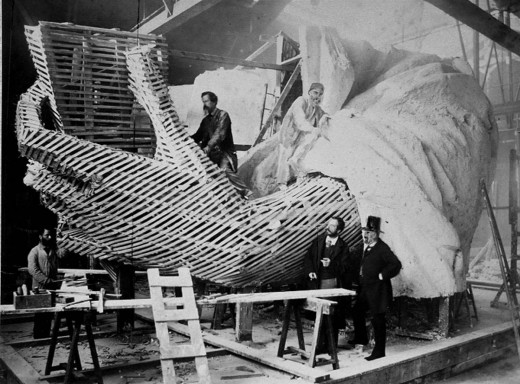

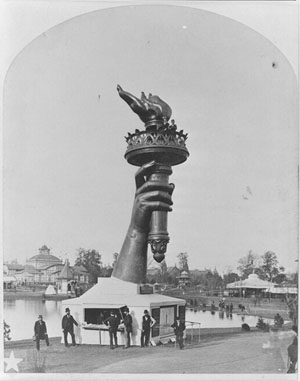

Law dragged his 100-pound parachute into the elevator, and in company with one of his foreman went aloft to the head of the Goddess. There he dressed his ropes and started up the remaining 50 feet through the mighty biceps and forearm until he reached the hand with supports the torch. There is an observation platform at this point which, since the issue of a recent order, cannot be visited without a special permit. This platform is 151 feet from the base of the statue and about 225 feet above sea level. It is large enough to hold twelve persons, and Law and his assistant had no trouble in arranging the parachute so that on the jump it would slide easily over the edges of the railing.

Law dragged his 100-pound parachute into the elevator, and in company with one of his foreman went aloft to the head of the Goddess. There he dressed his ropes and started up the remaining 50 feet through the mighty biceps and forearm until he reached the hand with supports the torch. There is an observation platform at this point which, since the issue of a recent order, cannot be visited without a special permit. This platform is 151 feet from the base of the statue and about 225 feet above sea level. It is large enough to hold twelve persons, and Law and his assistant had no trouble in arranging the parachute so that on the jump it would slide easily over the edges of the railing.

Awaiting a lull in the wind Law chose the eastern side of the statue for his descent, and at exactly 2:45 P.M., with all the moving picture machines trained in his direction, he jumped from the top of the railing, clearing the edges by ten feet.

Whistles shrieked in the harbor, and every one within seeking distance held his breath while the bulky parachute followed the man over the railing. There was fear of a tragedy for a moment, for the steeplejack fell fully seventy-five feet like a dead weight, the parachute showing no inclination whatever to open at first.

When it opened the wind blew it clear of the statue. Then Law began waving his hands frantically. It was not a sign of alarm, merely a steering method which the young aeronaut had adopted to keep his craft out of the bay. It proved practical, too, for the parachute descended gracefully.

When it neared the surface it seemed to fall fast for a moment, and Law, forgetting to jump, fell heavily on the stone coping, thirty feet from the water’s edge. He limped away from the pile of canvas and ropes, but declared that he was not injured. Later he packed up his parachute and personally carried it to his office in the Hudson Terminal Building. He did not want to be interviewed, he said.•