"It was only when she espoused the abolition cause that she lost the social position that she made for herself."

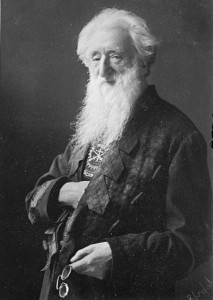

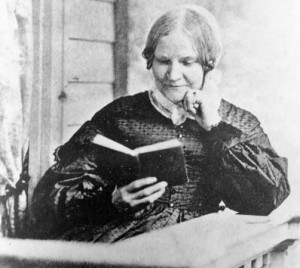

“Over the River and through the Woods” is a comforting song of home and family, but its author, Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), had a way of making people uncomfortable. A popular writer who surrendered her career to agitate for the abolitionist cause, Child was on the right side of history even if it cost her part of her career.

An article in the October 21, 1880 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle memorialized the author, if sometimes in a backhanded way. It’s a pretty good bet that the Eagle in that year didn’t have a single female journalist or editor, so this remembrance has a fair amount of praise but is still marked by a condescending attitude toward Child and all women. An excerpt:

“Lydia Maria Child, who died yesterday at her home on Wayland, Mass., was in many respects one of the most noted of her sex in this country. Her literary career covered a period of more than half a century, and her record was a consistent, persistent and for the most part a popular one. So long as she confined herself to writing she was eminently popular, and it was only when she espoused the abolition cause that she lost the social position that she made for herself.

She was preeminently an American product. The daughter of a humble baker, she became the most widely known of American female writers, with one exception–Mrs. Stowe–and like that writer, she owed her great celebrity to her espousal of the anti slavery cause. English people, who had little respect for American culture, gladly recognized the advocates of that cause in this country, and augmented the fame of all such. It was a time in the history of the country when few women were before the public, and none in this country had become famous outside of letters.

"As a woman, she possessed, in a marked degree, qualities not generally common to her sex."

Mrs. Child endeared herself to women by some of the earliest pen work she did, which was on household topics and home education, and the later work she did for her sex made her name an honored one. She was distinctively a woman writer, finding her subjects in the domestic world and doing her best work for the elevation of her sex in social and educational directions. As she grew in years she developed larger humanitarian views, and like Lucretia Mott, she gave her time and talents to a cause which brought her no fame as a writer, though it placed her in the front ranks of the agitators and deprived her of all the social distinction that had followed in the wake of her literary success. With Harriet Martineau, Fredrika Bremer and other English women who visited the United States about the time that the agitation was at its height, she waged a pamphlet war and gave up more lucrative employment for the sake of the cause of anti-slavery. We of to-day know Mrs. Child only as a writer, many years having elapsed since she retired from the world to live in retirement, surrounded by her family. Her last public work in the anti-slavery cause was a controversy she had with Governor Wise, of Virginia. in reference to a letter she had written to John Brown, offering to go and nurse him in prison.

As a woman, she possessed, in a marked degree, qualities not generally common to her sex. She was fearless and honorable in all her dealings, and wrought out her task independently and with consistency. Self education she urged as the essential precursor of all other tasks, and she worked to teach women to be broad and wisely liberal, to be united in all their public undertakings and to so serve their own higher needs that the succeeding generation might give enduring evidence of the capabilities and culture of American women. In her career of fifty years she exemplified the principles she advocated, and in her death the public has lost a wise teacher, and a brave and true representative of literature and philanthropy.”