In a recent Guardian essay, Stephen Hawking identified our age as the “most dangerous time for our planet.” Considering climate change, wealth inequality, the retreat of liberal democracy, and, perhaps, a re-embrace of nuclear proliferation, the physicist may very well be correct. While I thought his prescriptions to address the widening chasm between haves and have-nots were noble, they didn’t seem realistic to me. I have serious concerns that we’re increasingly taking a horrifying path.

In a Washington Post op-ed, Vivek Wadhwa feels similarly about Hawking’s best intentions. He suggests a better answer might be citizens having a greater voice in the nature of the technological tools shaping our future, though I’m dubious if that will make a dent, either. Technology isn’t often directed by a succession of sober-minded, rational choices. An excerpt:

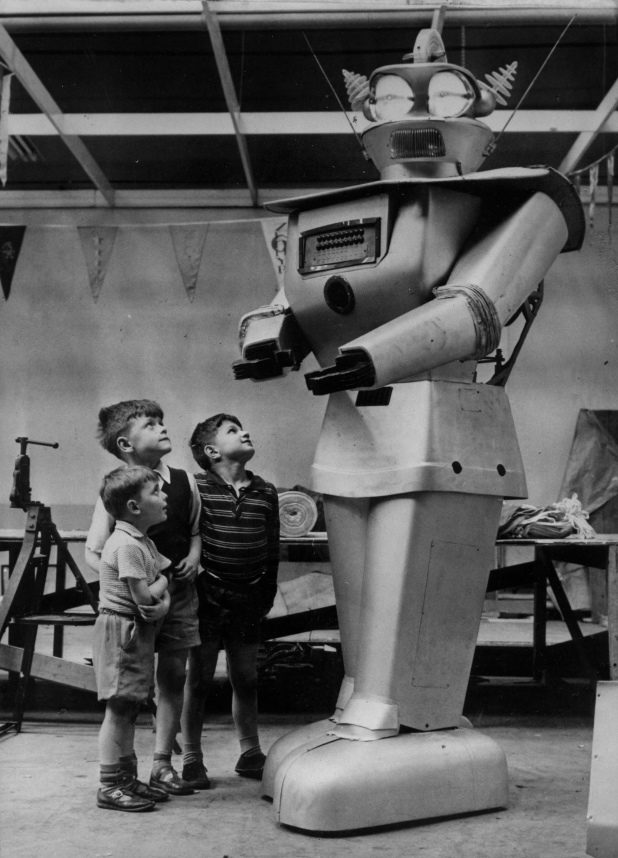

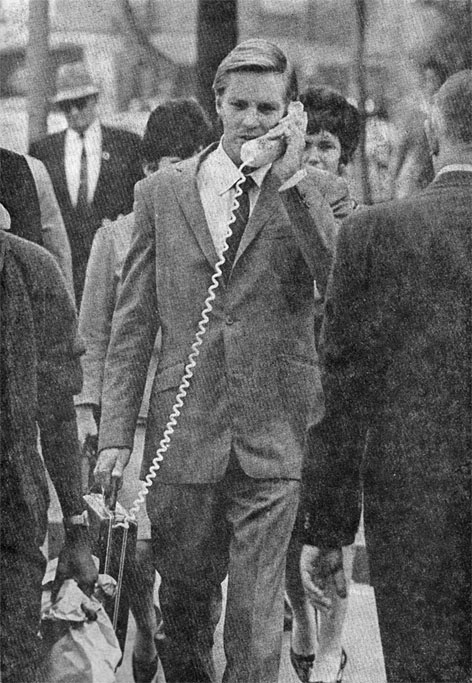

Technology is the main culprit here, widening the gulf between the haves and the have-nots. As Hawking explained, automation has already decimated jobs in manufacturing and is allowing Wall Street to accrue huge rewards that the rest of us underwrite. Over the next few years, technology will take more jobs from humans. Robots will drive the taxis and trucks; drones will deliver our mail and groceries; machines will flip hamburgers and serve meals. And, if Amazon’s new cashierless stores are a success, supermarkets will replace cashiers with sensors. This is not speculation; it is imminent. (Amazon founder Jeffrey P. Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

The dissatisfaction is not particularly American. With the developing world coming online with smartphones and tablets, billions more people are becoming aware of what they don’t have. The unrest we have witnessed in the United States, Britain and, most recently, Italy will become a global phenomenon.

Hawking’s solution is to break down barriers within and between nations, to have world leaders acknowledge that they have failed and are failing the many, to share resources and to help the unemployed retrain. But this is wishful thinking. It isn’t going to happen.

Witness the outcome of the elections: We moved backward on almost every front. Our politicians will continue to divide and conquer, Silicon Valley will deny its culpability, and the very technologies, such as social media and the Internet, that were supposed to spread democracy and knowledge will instead be used to mislead, to suppress and to bring out the ugliest side of humanity.•