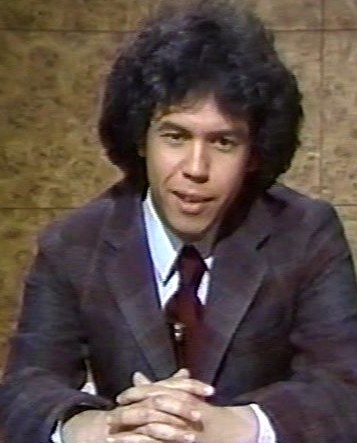

Comedic character actor and playwright Taylor Negron, whose numerous appearances on the Dating Game somehow made it even gamier, just passed away from cancer at the young age of 57. I don’t know for sure that it’s the last thing he wrote, but he penned a charming and raffish memoir about his exploits in a pre-social media Hollywood for the June 2014 issue of the wonderful Lowbrow Reader. It’s filled with amusing tales of Rodney and Robin and others who sought his supporting skills and simpatico. An excerpt:

My first comedy gig was on the boardwalk in Venice Beach, performing in a group called the L.A. Connection. Our audience was composed predominantly of hippies who had been kicked out of Big Sur for urinating on the redwoods. It was more akin to the circus than to comedy—we had to bark up the crowd, like in an old black-and-white movie. After one of our shows on the expansive green lawn, an elfin man approached and, speaking in a crisp brogue, told me how much he enjoyed the performance. He claimed to be from Dublin. I had never met anybody from Ireland, and savored his screwy Lucky Charms accent. He attended our shows week after week.

We became close enough that one day, the leprechaun was forced to come clean: He did not hail from Dublin and his accent was fake. He was an American actor named Robin Williams, preparing to star in a sitcom called Mork & Mindy. He asked me to hang out with him at Paramount Studios. Sitting on the bleachers, I watched my fake Irish friend portray a space alien. “This show,” I thought, “will never fly.”

I was wrong, of course. Robin struck a chord; before I knew it, he was on the cover of Time. For a brief moment, I became a select member of his posse and we ended up in an improv group together, the Comedy Store Players. We had lines around the block. After shows, there would be great commotion in the dressing room as it filled with Lou Reed lookalikes named Hercules and Raquel, all shaking tiny bottles of cocaine.

Robin loved cocaine and we loved Robin, so we went with Robin to parties with sniff in the air. I did not enjoy cocaine. It made me want to vacuum every hallway in every apartment building in the world. I quickly learned the art of pretending to do cocaine—this being Los Angeles, fake drug abuse was generally as acceptable as actual drug abuse—by putting one end of the mini-straw into my nose and the other end to the side of the acrid substance. It was like moving Brussels sprouts around one’s plate as a child.

One night, we went to Harry Nilsson’s house in Bel Air. A mid-century poem of a home, surrounded by oaks, ferns and delphiniums, it looked like a house painted by Thomas Kinkade, if Thomas Kinkade was in the fourth stage of heroin abuse. The only light in the house came off of a bong. The famous did lines off beveled glass-mirrored tables. Nilsson busted me. “I see what you’re doing,” the musician said. “You’re faking doing cocaine.” I felt so humiliated, worried that I would get that early ’80s lecture: Don’t you know there are people in the Valley going to bed tonight without any cocaine at all?•