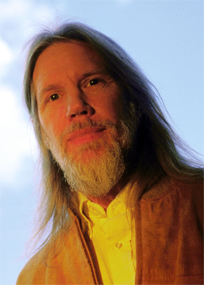

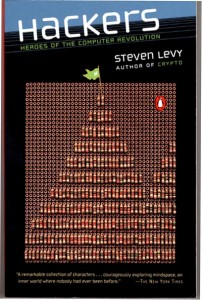

Nobody calls anymore: It’s all texts, tweets and emojis. Phones are ever-more sophisticated, but most functions are silent. There are attempts, however, to remake the 135-year-old tool to fit the more fluid demands of what is becoming a post-voice world, though privacy may again suffer collateral damage. The opening of “Brave New Phone Call,” a just-published Medium piece by Steven Levy, the leading tech journalist of the personal-computing era:

“It is a gorgeous late summer afternoon, and I am sitting with Ray Ozzie in his spacious home office in Manchester-by-the-Sea, 30 miles up the coast from Boston. The software visionary who created Lotus Notes and who later succeeded Bill Gates as Microsoft’s chief software architect, is explaining to me how the humble phone call is not dying, as many might believe, but is busy being reborn.

It’s not an abstract subject for the 58-year entrepreneur. For the past few weeks I have been using the app his company is announcing today, called Talko. It’s a weird, almost magical, combination of phone calling, text messaging, virtual conferencing and Instagram-ish photo sharing. Depending on how you view it, Talko is three or 39 years in the making.

At one point, Ozzie wants to show me something on the app. We both pull out our iPhones and connect with each other; actually, in that moment, we reconnect to a conversation we’ve been having all month that’s been recorded and archived in the app. I think my editor might be interested in the discussion, so we expand the conversation to include him. He’s unable to join us at the moment—I should have known, because the app lets me see that he’s walking around somewhere on the West Coast—but I shoot a photo for him to look at anyway, and Ozzie and I continue talking. Later, my editor will listen to that part of conversation and see the picture at the moment we shot it. And he’ll have the option to comment, perhaps kicking off a longer discussion down the road, either by convening us together in real time or continuing in the same piecemeal fashion as today.

That’s a typical Talko phone call—mixing presence and playback for a totally new experience. God knows that the old experience of a phone call is getting tired.

A few days later, to note the irony of it all, Ozzie sends me a photo in the same ongoing conversation. It’s a plaque in downtown Boston, a block from a Talko engineering office there:

BIRTHPLACE OF THE TELEPHONE

Here on June 2, 1875, Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas A. Watson first transmitted sound over wires.

That phone call represented an amazing advance in communications. But Ozzie considers it equally amazing that in the 139 years since ‘Mr. Watson, come here,’ phone calls haven’t changed much.”

________________________________

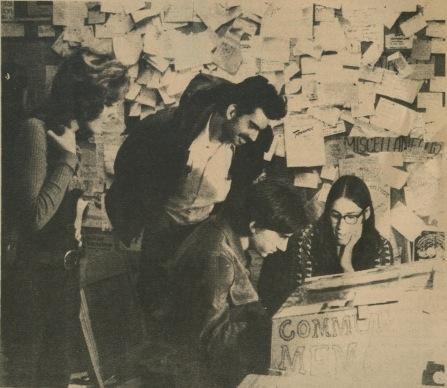

Debut of the Picturephone, 1970: