Extremely long-term predictions are the safest bets we can make, not only because we’ll be long gone by the hour of reckoning (unless immortality becomes possible, which some predict), but because pretty much anything we can dream up–and lots we can’t–will come to pass should we snake our way through the Anthropocene and carry on for hundreds of thousands or even millions of years.

Prognostications aimed a few decades in the future are the most fraught, yet we have no choice but to continually forecast since we have to set policy for not only now but for several generations. In a Financial Times review of a slate of books about predicting tomorrow, philosopher Stephen Cave asserts that “rarely can the future be predicted by simply extending current trajectories,” while acknowledging that we must at least try to envision what’s possibly next. His opening:

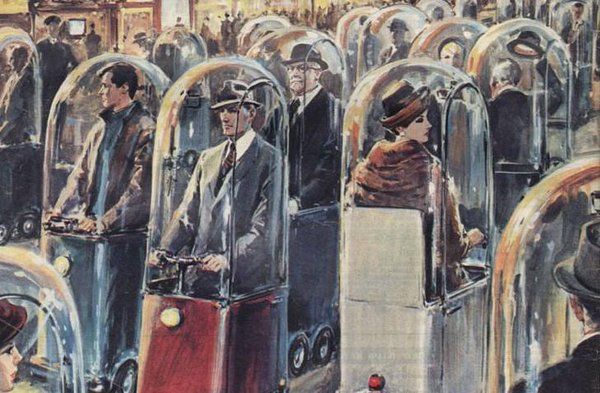

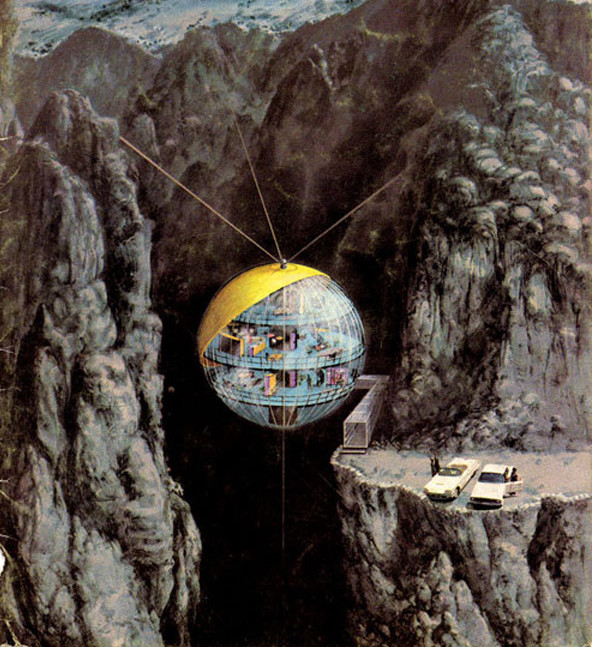

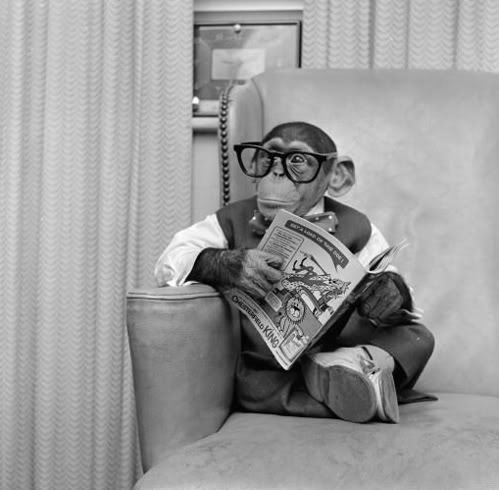

As a boy, I enthusiastically read the British comic 2000 AD. It told sci-fi tales set in the far future — which at that point meant any date after 1999. Judging by its stories, it seemed obvious back then that at the dawn of the next millennium we would be riding our hover-boards to engage in laser battles with rogue robots — though only, of course, if we survived the coming nuclear apocalypse.

Now it is 2016, a date so far into the future that it gives me vertigo. But it is not the future of my teenage imaginings. We were spared the apocalypse; the cold war ended as suddenly as a computer game switched off by a bored child. Instead of rogue robots, we are battling religiously motivated terrorists. And in place of a laser gun, I have an internet-enabled smartphone — a far more wondrous device that is transforming many aspects of our lives but which was entirely unforeseen by anyone in the 1980s.

Given no one a few decades ago successfully predicted how the world would be today, we might wonder whether we have any hope of predicting how it will be 10, 20 or 50 years from now. Yet we are compelled to try. We are not passive observers of an unfolding drama, but actors shaping the story — and with a strong interest in how it turns out. Every time we take a new job or make a decision about our children’s education, we are speculating about how events will unfold. This makes us all both forecasters and visionaries, attempting to read the trends and at the same time to create the future that we want for ourselves.•