If you trail down the lesser-remembered paths of Robin Williams’ career, you start to reacquaint yourself with stuff like his lead in the television adaptation of Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day or his appearance on the second season of Homicide: Life on the Street. That show was adapted from then-Baltimore newspaper reporter David Simon’s book, and the future creator of The Wire was only a part-time TV writer when Williams guested on the ratings-challenged program. Simon has written a recollection of his meeting with the great actor, and I hope he wouldn’t think the segment I’m posting below too long. It’s a story that builds, and I felt like a mohel with a hacksaw each time I approached it for more cutting. The excerpt:

“I wanted to offer something — anything — and I thought about the Penn Street morgue in which we were standing.

‘Have you ever heard of the Nutshell Studies?’

He had not, of course.

‘They’re upstairs, off the hallway up there. I can show you. It’s not anything you could imagine, and since we’re actually in the morgue today…’

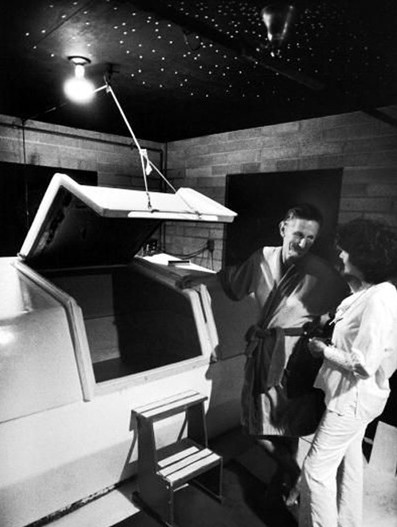

He nodded, a bit wearily, I thought, and a nervous production assistant followed us upstairs as I tried to explain the dollhouse-sized dioramas that were on display at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner here in Baltimore. Created as part of the Francis Glessner Lee Seminar for death investigation, a training regimen for police detectives originally funded by Harvard University, each diorama featured the occupants of a dollhouse room in the aftermath of violent death. The scenes were carefully detailed, and a detective in the seminar, as part of his final exam, could stare down at a tableau and determine, from the evidence in each room, whether the doll in question had died accidentally, taken his or her own life, or been willfully murdered.

Mr. Williams looked at each of the rooms, asking questions, fascinated by the macabre display. He guessed at a seemingly accidental death that was in fact a murder, then guessed again at a kitchen suicide by a young girl that seemed at first glance to be a stabbing. I could offer solutions to most of the displays only because I’d learned the answers, years before. The actor took it all in, clicking the buttons to light each diorama and then staring at all of the morbid goings-on until the P.A. told him he was needed back on set.

‘How long has that been here?’ he asked as we walked back.

‘They’re from the 1940s, I think.’

He nodded solemnly. Not a joke to be had.

He smiled for just a moment, but followed the P.A. back downstairs to the set, where the grips and gaffer were still lighting. And then, suddenly, it happened. Nothing specifically to do with the dollhouse horror show, or even the fact that we were filming in a working morgue, but instead the arrival of Mr. Levinson, the executive producer. I wish I could remember the sequence, but there is no way in hell:

It began, I think, with something about Barry arriving as a mohel to circumcise the cast and crew, replete with an imitation offered up with Hasidic accent, then lurched into a string of jokes about how reluctant crew members could opt for an antemortem autopsy downstairs if they didn’t want to be so fixed by Mr. Levinson. There was a segue into all the other morbid Baltimore locales that would be featured in the episode, and all of the ghoulish degradations that would be endured by the crew, following by some savagery about the film caterer and then some banter with Mr. Belzer, who tried to hang for a few bon mots. But no, Robin Williams was firing all rockets, leaving earth’s orbit. I can’t remember all of the sparks of comic synapse, the absurd connections, the twisting journey from one punchline to the next. I have a specific recollection of him announcing Mr. Levinson’s new NBC drama as The Pope and Judy, a warm-hearted romp that would make everyone forget that depressing mess about murders in Baltimore: ‘He’s the supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church; she’s an adorable puppet.’

And then a mock-Italian voice, as a pope tries to fellate a falsetto-voiced puppet — the comedian’s left hand — with a communion wafer.

You had to be there. And, yes, I know that the phrase is used to connote moments that are less humorous in retrospect, but with Mr. Williams the live-wire volatility, the no-net comic gymnastics was part of the allure. If you were there, and I was, then you could scarcely breathe from laughing so hard and so long. The crew stopped working, forming a semicircle around him. Word went down the hallway and out to the trucks. More people rushed in to catch the shooting sparks, so that the entire production came to a halt as Robin Williams, quiet for days in the role of a grieving, wounded man, finally exploded. He was soaring for at least another five minutes before Mr. Levinson gave the slightest nod to his watch: We were losing the day.

Mr. Williams caught the look from the producer and ended the impromptu routine abruptly, with an awkward smile. His breathing was labored, and he looked to be genuinely embarrassed by his demonstration as cast and crew applauded with warm delight before returning to work. But it seemed that the actor had gone there as much for his own needs as for the audience, that he had come back downstairs from the dollhouse of the dead, readied himself to shoot another painful scene of grief and guilt, and then, in manic desperation, reached out for as much human comedy as ten minutes will allow.

I last saw him in the hallway, using the few remaining minutes before filming to face the wall and reacquaint himself with whatever horror he was trying to channel. He was sweating, too, as if it had taken all he had to rise to that warm summit and provoke such laughter. To my great surprise, his face was that of an unhappy man, and I retreated, saddened and surprised by the thought.”