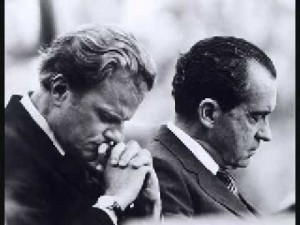

Trump is certainly not Nixonian in intellect or policy, but he shares with his predecessor an utter disregard for truth, a deep paranoia that mints enemies like pennies and a nefariousness that will probably lead to disgrace if not tragedy. His sense of being cheated, a rich man who feels deeply impoverished, has its origins in a Rosebud-ian psychological wound and perhaps some mental illness, has rendered him extremely immoral and deeply disturbed. In the country’s future–should there be one–it will be possible to have a worse President if that person retains all his terrible qualities but is basically competent. We should be glad of his ineptitude, provided it doesn’t get us all killed.

On the day when the Washington Post delivered what appears to be a bombshell about a terrible breach by Trump in the company of his Russian comrades, a misstep to be added to his litany of lies, acts of kleptocracy and attacks on American democracy, here’s a piece from Garry Willis’ 1974 New York Review of Books piece about Woodward and Bernstein’s All the President’s Men:

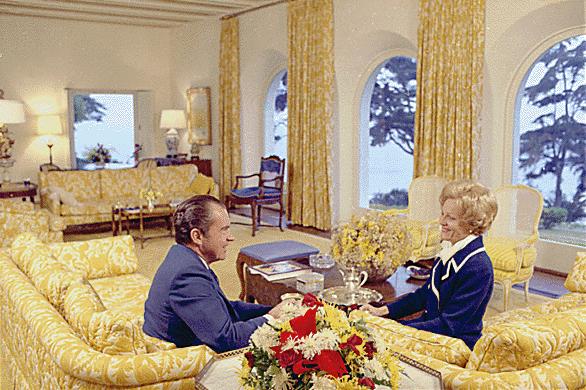

Nixon was always Wronged; so, since the score could never be settled entirely, he felt no qualms about getting back what slight advantage he could when no one was looking. Even at the height of his power, he feels he must steal one extra vote, tell the marginal little lie. He is like a man who had to steal as a child, in order to eat, and acquired a sacred license—even a duty—to steal thenceforth; it would punish the evil that had first deprived him. Thus he took as his intimate into the Oval Office the very man who helped him try to cheat his way into the office of governor of California. Those who say Nixon did not know what kind of thing his lieutenants were up to forget that the judge who decreed in favor of plaintiffs in the fake postcard-poll case of 1962 did so on the grounds that both Haldeman and Nixon knew about the illegal tactic. Watergate is the story of a man who has just pulled off a million-dollar heist and gets caught when he hesitates to steal an apple off a passing vendor’s cart.

Nixon engages in a kind of antipolitics; a punishment of politics for what it has done to him. That is why he could never understand “the other side” in the Washington Post’s coverage of the Watergate investigation. Jeb Magruder has written that his staff was pleased when two unknown local reporters, Bernstein and Woodward, were given the break-in as their assignment. When the story did not lapse after a decent interval, Nixon conceived it as an ideological vendetta directed by Katharine Graham for the benefit of George McGovern—something to be countered by high-level threats, intimidation, and “stonewalling.” Even Henry Kissinger tried to intervene with Mrs. Graham.

Actually, if the coverage had been political, it might have failed. Very few columns or editorials played up Watergate in the election period, even at the Post. Those wanting high political sources and theoretical patterns would not have found the sneaky little paths under out-of-the-way bushes, as Woodward and Bernstein did. They thought, from the outset, they were dealing with robbers, not politicians. When their tips kept leading them toward the White House; they balked repeatedly, out of awe and fear and common sense; but the evidence kept tugging them against the pull of expectation. The editors kept them at it, but gave them little help. They must pursue their modest leads even after they wanted to be switched to “the big story” at the Ervin hearings. Others would theorize, editorialize, do the White House circuit. Theirs was the leg work, the endless doors knocked on, wrong numbers called, the days of thirty leads checked out and nothing to show for it. A leitmotiv of the book is “back to square one.”

They advanced, as it were, backward—always back to the same sources; would they talk this time? No. Then put them on the list of people to go back to. Back and back. Which became up and up. Up, scarily at the last, “to the very top” (as the Justice Department man had put it). Their sources—originally secretaries and minor functionaries—were added to when parts of the gang like Dean started dealing to get out; but there had always been people who talked because they were sincerely shaken by what was going on—not only Hugh Sloan at the outset, but the mysterious White House cooperator called “Deep Throat.” It is good to know the gang could not entirely succeed in imposing its code of omertà.•