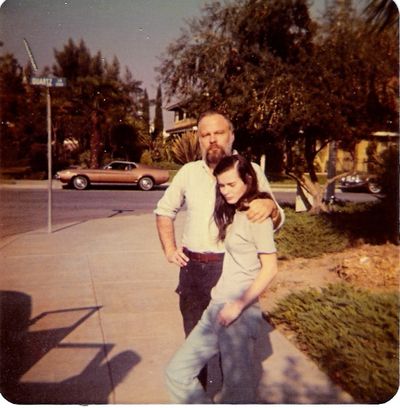

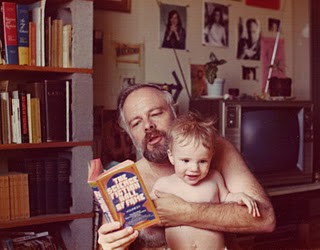

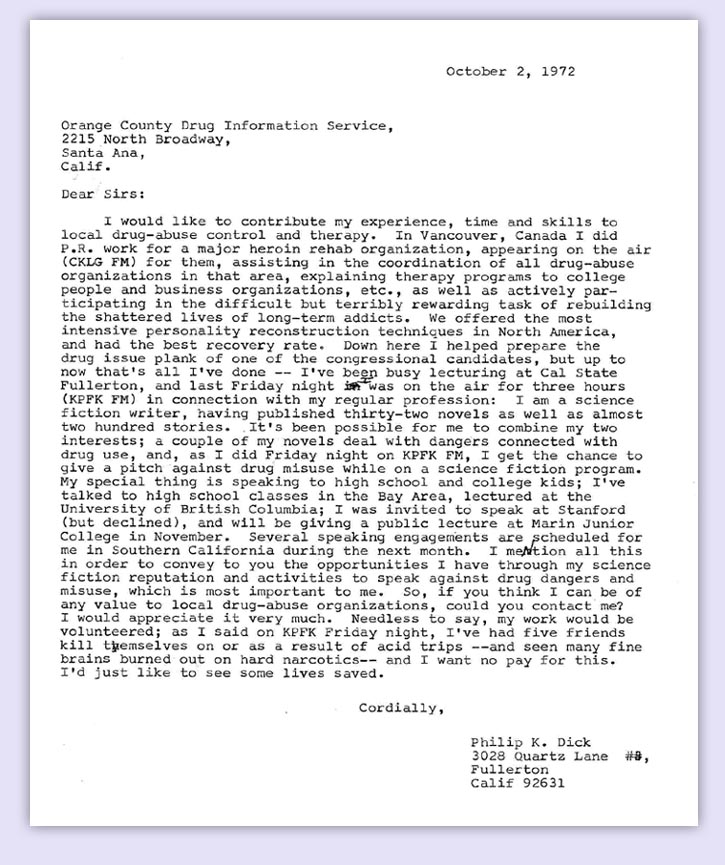

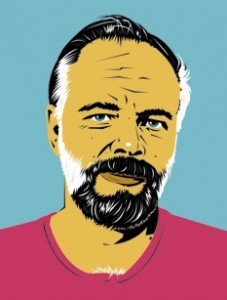

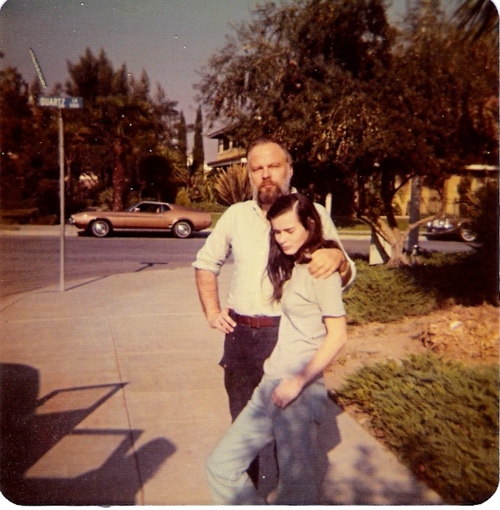

In a Literary Review piece about Kyle Arnold’s new title, The Divine Madness Of Philip K. Dick, Mike Jay, who knows a thing or two about the delusions that bedevil us, writes about the insane inner world of the speed-typing, speed-taking visionary who lived during the latter stages of his life, quite appropriately, near the quasi-totalitarian theme park Disneyland, a land where mice talk and corporate propaganda is endlessly broadcast. Dick was a hypochondriac about the contents of his head, and it’s no surprise his life was littered with amphetamines, anorexia and anxiety, which drove his brilliance and abbreviated it.

The opening:

Across dozens of novels and well over a hundred short stories, Philip K Dick worried away at one theme above all others: the world is not as it seems. He worked through every imaginable scenario: consensus reality was variously a set of implanted memories, a drug-induced hallucination, a time slip, a covert military simulation, an illusion projected by mega-corporations or extraterrestrials, or a test set by God. His typical protagonist was conspired against, drugged, hypnotised, paranoid, schizophrenic – or, possibly, the only person in possession of the truth.

The preoccupation all too clearly reflected the author’s life. Dick was a chronic doubter, tormented, like René Descartes, by the suspicion that the world was the creation of an evil demon ‘who has directed his entire effort to misleading me’. But cogito ergo sum was not enough to rescue someone who in 1972, during one of his frequent bouts of persecution mania, called the police to confess to being an android. Dick took scepticism to a level that he made his own. It became his brand, and since his death it has been franchised across popular culture. He isn’t credited on Hollywood blockbusters such as The Matrix (in which reality is a simulation created by machines from the future) or The Truman Show (about a reality TV programme in which all but the protagonist are complicit), but their mind-bending plot twists are his in all but name.

As Kyle Arnold acknowledges early in his lucid and accessible study, it would be impossible to investigate the roots of Dick’s cosmic doubt more doggedly than he did himself. He was ‘his own best psychobiographer”…•