The transformation of heiress Patty Hearst from debutante to terrorist after her 1974 abduction by the Symbionese Liberation Army is endlessly interesting as a study in extreme psychological metamorphosis, though its fascination four decades ago lie mostly mostly in its more lurid aspects, the violent collision of rich and poor, of high society and anti-social impulses, the sacred taking up with the profane. It was worlds colliding, an impact that made the masses feel unsafe, that so fixated the nation. The Lindbergh baby was alive and conspiring with the kidnappers. Anything, it seemed, was possible, and how could that be good?

The transformation of heiress Patty Hearst from debutante to terrorist after her 1974 abduction by the Symbionese Liberation Army is endlessly interesting as a study in extreme psychological metamorphosis, though its fascination four decades ago lie mostly mostly in its more lurid aspects, the violent collision of rich and poor, of high society and anti-social impulses, the sacred taking up with the profane. It was worlds colliding, an impact that made the masses feel unsafe, that so fixated the nation. The Lindbergh baby was alive and conspiring with the kidnappers. Anything, it seemed, was possible, and how could that be good?

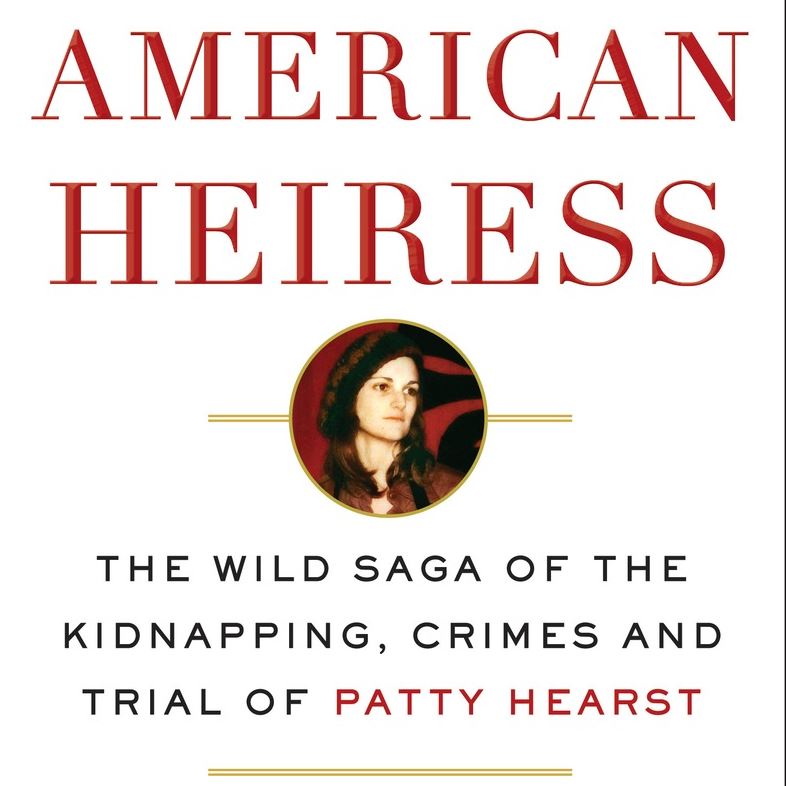

Jeffrey Toobin, the wonderful New Yorker writer and legal analyst, just published American Heiress, a book about the scion-gone-wild, though he’s fully cognizant that titles about the crimes of the rich and famous, “Tania” or O.J., for whatever they may tell us about America, aren’t nearly the most important stories to tell. One exchange from a recent New York Times interview with Toobin:

What’s the last great book you read?

Jill Leovy’s Ghettoside. Meticulously reported and gracefully written, this book captures the horror of urban violence in Los Angeles. At roughly the same time as Leovy was shadowing L.A.P.D. detectives in East L.A., I was across town, covering O. J. Her book made me think twice about what counts as a “big” story.

That’s the truth, though Hearst’s case speaks to the seismic shift young people (and some older ones) can make, whether we’re talking about her, Manson Family members, Jonestown joiners or ISIS acolytes.

Three pieces follow: 1) An excerpt from Dana Spitotta’s NYT review of Toobin’s title, 2) A segment of a 1974 People interview with psychiatrist Dr. Frederick J. Hacker, who consulted with the family while Patty was underground, and 3) A 1974 video of the devastated Randolph Hearst discussing his daughter’s life on the lam.

From Spiotta:

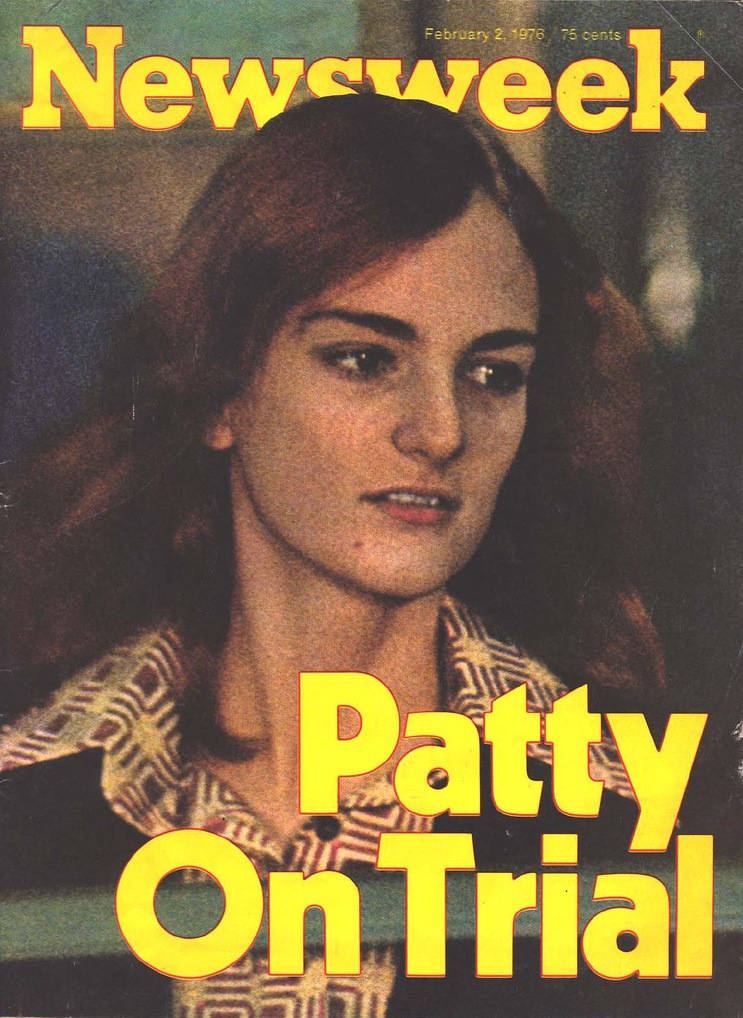

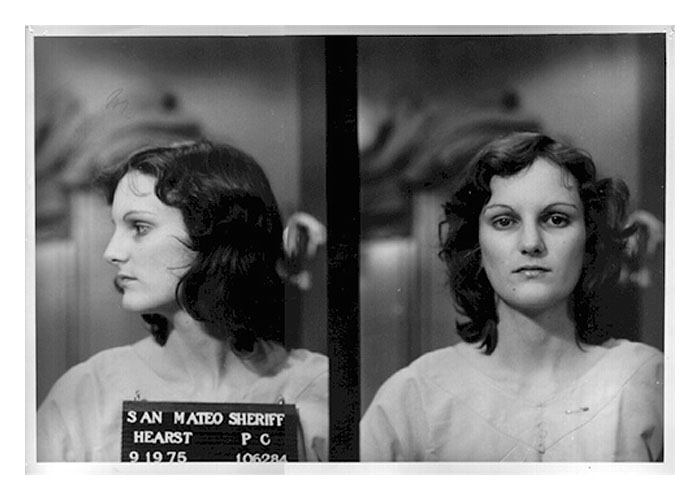

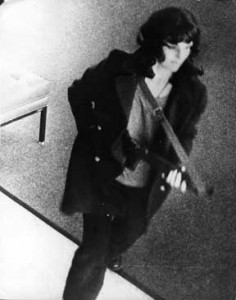

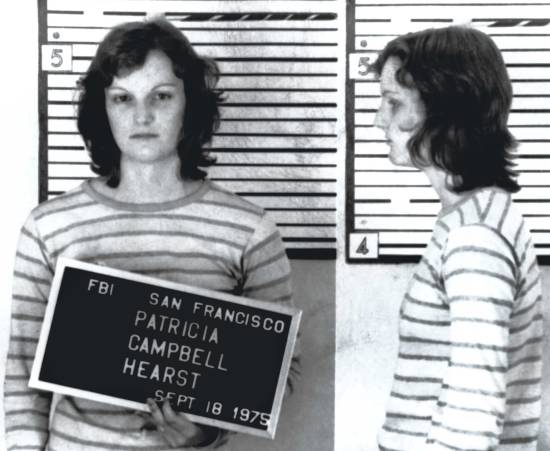

Perhaps the captivity story that has fascinated us the most is the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst, the subject of Jeffrey Toobin’s terrifically engrossing new book, “American Heiress.” The brief outline of the events will be familiar to many: Hearst was taken from her Berkeley apartment by the Symbionese Liberation Army, or S.L.A. (a tiny, slogan-drunk band of revolutionaries so obsessed with guns and publicity that they seem almost pre-satirized). After being held in a closet and haphazardly coached in guerrilla warfare and revolutionary theory, Hearst declared — in a notorious message delivered in a mesmerizing combination of “breathy rich-girl diction” and “pidgin Marxist” jargon — that she was now “Tania,” that she had not been brainwashed and that her captors had offered to let her go, but “I have chosen to stay and fight.” She then helped to rob banks (in which one bystander died) and plant bombs until she was apprehended in 1975. In custody, she claimed that all of her crimes were committed under duress. Her lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, built his defense on the argument that she had acted out of “coercive persuasion” (Stockholm syndrome was not yet a common concept). She was found guilty and served nearly two years of her sentence before President Carter commuted it to time served.

Was Patricia Hearst responsible for her crimes, or was she a victim who did what she needed to do to survive? Or is the truth somewhere in between? The story has been the subject of many books — some dozen are listed by Toobin. Also inspired by the case: two novels (“Trance,” by Christopher Sorrentino, and “American Woman,” by Susan Choi), a feature film, several documentaries, at least two porn movies and an episode of “Drunk History.” Hearst herself wrote a book. Yet the questions remain unresolved, which is one reason for Toobin to investigate. Another is that he sees the episode as “a kind of trailer for the modern world” in terms of celebrity culture, the media and criminal justice.•

As surprising as it is that so many middle-class youths are drawn today via social media to ISIS, Patty Hearst, practically American royalty, being kidnapped in 1974 by the SLA and then converted somehow to its terrorist cause, completely stunned the world. She didn’t go willingly, but she became a willing accomplice, brainwashed probably, though a lot of Americans were unforgiving. It seems like some of the same factors that work for ISIS may have helped the SLA remake the debutante as “Tania.” Whatever the situation, USC psychiatrist Dr. Frederick J. Hacker, whom the family hired while she was still on the lam to help them understand their daughter’s descent into terrorism, probably should not have discussed the case with Barbara Wilkins of People magazine while she was still at large, but he did. An excerpt:

Question:

Why did the Hearsts consult you?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

I had published a book on terrorism in Germany in 1973—dealing with the Olympic tragedy in Munich and the Arab-Israeli situation. In September ’73, I became a negotiator in Vienna between the government and two Arab terrorists. After that, I was invited to speak at Harvard and the State Department and to testify before the House Committee on Internal Security. That was how the Hearsts heard about me and my work.

Question:

When did you get involved in the case of Patricia Hearst?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

When a Mr. Gould of the Hearst newspapers called me up, on behalf of the family, about four weeks after the kidnapping. I went up to Hillsborough to visit the Hearsts. I told them to take the SLA at face value, to take the political message seriously. And I urged them to get a concession for every concession they made.

Question:

What have you discovered about Patty Hearst?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

I had not known her before, of course. By now everyone has read what her life had been. She was an average, intelligent girl. She lived an unspectacular life with her former tutor. She was more liberal than her family but was still relatively conservative. She was totally without political interests. She was sheltered. She’d gone to Europe with some other girls and, prior to Steve [her fiance Steven Weed], she’d had three or four other boyfriends. She was never very close to any of her sisters. The oldest sister, a polio victim, had deep religious convictions. Patty had a bad relationship with her mother, but a fairly good one with her father. They could talk. When she was kidnapped, Patty was picking out her silverware pattern, because she had talked Steve into marrying her.

Question:

What is the lure of the SLA for a girl like Patty Hearst?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

In spite of everything, the sense of close proximity among these people gives a feeling of family, of community and caring. There is shared danger and a sense of strong commitment that is very impressive to the uncommitted.

Question:

Was Patty’s conversion voluntary?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

Everybody asks how voluntary her conversion was. I raise the question, “How intentional was the SLA’s conversion of Patricia?” Maybe they didn’t want to convert her at first. Let’s look at it this way. She’s kidnapped, and she’s frightened and inclined to believe these people are really monsters. Then they treat her very nicely. She begins to talk to them, to the girls. She finds they are very much the kind of people she is—upper-middle-class, intelligent, white kids. She finds a poetess, a sociologist. They tell her how they have found a new ideal and how lousy it was at home. Perhaps she started to think, “Well, at my home it wasn’t so hot either.” This may be what happened. There is a strong possibility, of course, that she was brainwashed. Maybe they did use drugs, although none was found in the bodies after the L.A. shoot-out. …

Question:

Was Patricia in on the kidnapping from the beginning?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

She was undoubtedly a genuine victim. All the talk that she was in cahoots is nonsense. All the evidence, in fact, is against it, including the testimony of her boyfriend, who has no conceivable reason to lie. Why did she have her identification with her? A kidnap victim doesn’t—unless someone else grabs it and takes it along.

Question:

What makes a terrorist?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

A number of different things. Usually the terrorist is imbued with the righteousness of his cause, and fanatacized by the idea of remediable injustice. For example, as long as you could tell women that it was God’s will that they were mistreated by men and that it was irremediable, there was no movement to change things. As soon as it becomes clear that an injustice is not fated, is not obligatory, and that there are alternatives, then the dominant group is in trouble.

Question:

Are there different kinds of terrorists?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

I distinguish three categories—the criminal, the mentally deranged and the political. With the SLA, it is not easy to confine them to one category. They are criminally involved because some of their tactics are criminal. Some actions are loony and the details are ludicrous. When Cinque’s body was found, he was wearing heavy pants, army boots up to his calf and three pairs of woolen socks—in Southern California where the temperature was 80°. He had a compass and a canteen. That’s inappropriate. They stole from that sporting goods store, but they certainly did not need the money. Hundreds and hundreds of dollars were found on all the bodies. Only the outside of the folded money burned. There were nutty elements. What kind of an army is 20 people, or 10 people? They were also political, and that is what made it so hard.

Question:

These radical movements seem to attract middle-and upper-middle-class children rather than the lower-middle-class and poor. Why?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

You are asking who becomes a revolutionary. The leaders of a revolution don’t come from the class they are trying to liberate. The to-be-liberated group doesn’t have the means to lead itself out of oppression.

Question:

What can be done about terrorism?

Dr. Frederick J. Hacker:

First, you must change the “remediable” conditions that produce the terrorist solution—for instance, somehow you get rid of the Palestinian refugee camps. Second, the mass media must effect restraint so that terrorist crime does not become fashionable. Finally, I believe we must establish task forces led by law enforcement executives who are advised by responsible behavioral scientists.•

This 1970s video contains comments Randolph Hearst made to NBC News about his daughter Patty, who was at the time doing a walkabout through the Radical Left. “I think she’s staying underground just like a lot of kids stay underground,” her clearly shaken father remarked, accurately assessing the situation. Before the end of the decade, she was captured, convicted, imprisoned and, controversially, had her sentence commuted. In January 2001, Bill Clinton felt it necessary to grant her a full pardon.