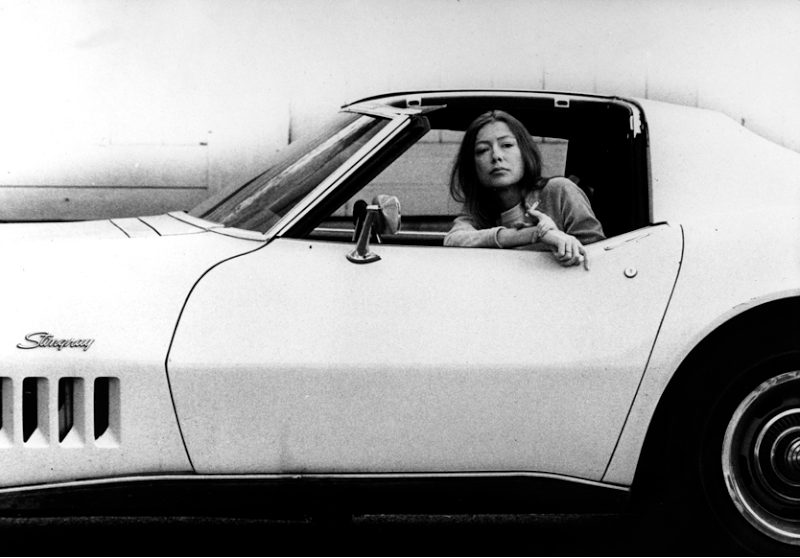

Image by Ted Streshinsky.

In his New Yorker piece about Tracy Daugherty’s Joan Didion biography, The Last Love Song, Louis Menand states that “‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ was not a very good piece of standard journalism.” Well, no. Nor was the Flying Burrito Brothers very good classical music, but each of those assessments is probably beside the point.

Menand claims Didion poorly contextualized the Hippie movement, but the early stages of his own article suffers from the same. He asserts the Flower Child craze and the thorny period that followed it was similar to the Beats of the previous decade, just weekend faddists lightly experimenting with drugs. But the counterculture of the late-1960s blossomed into a massive anti-war movement, a much larger-scale thing, and the youth culture’s societal impact wasn’t merely a creation of opportunistic, screaming journalism. Menand wants to prove this interpretation wrong, but he doesn’t do so in this piece. He offers a couple of “facts” of indeterminate source about that generation’s drug use, and leaves it at that. Not nearly good enough.

I admire Menand deeply (especially The Metaphysical Club) the way he does Didion, but I think her source material approaches the truth far more than this part of Menand’s critique does. Later on in the piece, he points out that Didion wasn’t emblematic of that epoch but someone unique and outside the mainstream, suggesting her grasp of the era was too idiosyncratic to resemble reality. But detachment doesn’t render someone incapable of understanding the moment. In fact, it’s often those very people who are best positioned to.

The final part of the article which focuses on how in the aftermath of her Haight-Ashbury reportage, Didion had a political awakening from her conservative California upbringing, though not an immediate or conventional one. This long passage is Menand’s strongest argument.

An excerpt:

“Slouching Towards Bethlehem” is not a very good piece of standard journalism, though. Didion did no real interviewing or reporting. The hippies she tried to have conversations with said “Groovy” a lot and recycled flower-power clichés. The cops refused to talk to her. So did the Diggers, who ran a sort of hippie welfare agency in the Haight. The Diggers accused Didion of “media poisoning,” by which they meant coverage in the mainstream press designed to demonize the counterculture.

The Diggers were not wrong. The mainstream press (such as the places Didion wrote for, places like The Saturday Evening Post) was conflicted about the hippie phenomenon. It had journalistic sex appeal. Hippies were photogenic, free love and the psychedelic style made good copy, and the music was uncontroversially great. Around the time Didion was in San Francisco, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and soon afterward the Monterey Pop Festival was held. D. A. Pennebaker’s film of the concert came out in 1968 and introduced many people to Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Ravi Shankar. Everybody loved Ravi Shankar.

Ravi Shankar did not use drugs, however. The drugs were the sketchy part of the story, LSD especially. People thought that LSD made teen-age girls jump off bridges. By the time Didion’s article came out, Time had run several stories about “the dangerous LSD craze.” And a lot of Didion’s piece is about LSD, people on acid saying “Wow” while their toddlers set fire to the living room. The cover of the Post was a photograph of a slightly sinister man, looking like a dealer, in a top hat and face paint—an evil Pied Piper. That photograph was what the Diggers meant by “media poisoning.”•