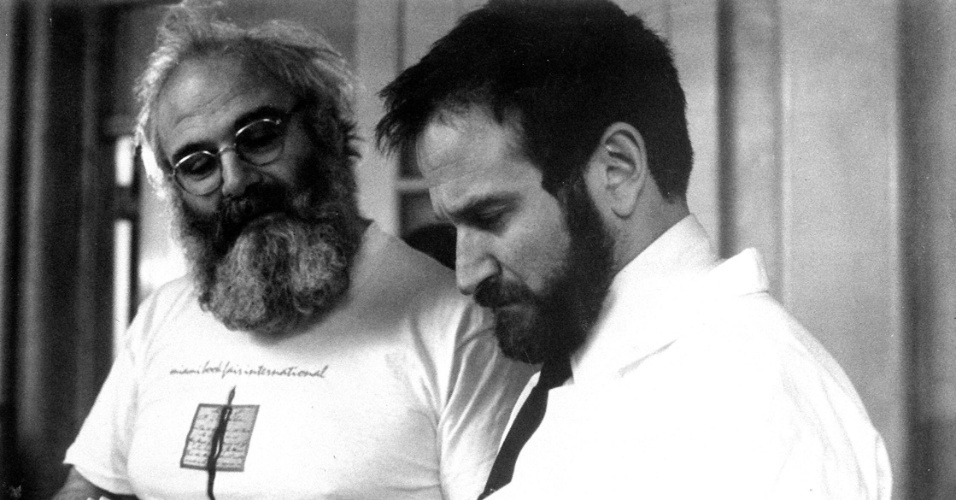

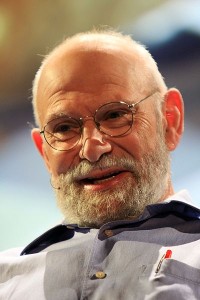

Sad to hear of the passing of Dr. Oliver Sacks, the neurologist and writer, who made clear in his case studies that the human brain, a friend and a stranger, was as surprising as any terrain we could ever explore. It feels like we’ve not only lost a great person, but one who was uniquely so. He became hugely famous with the publication of his 1985 collection, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, which built upon the template of A.R. Luria’s work with better writing and a wider array of investigations. Two years prior, he published an essay In the London Review of Books that became the title piece. An excerpt:

I stilled my disquiet, his perhaps too, in the soothing routine of a neurological exam – muscle strength, co-ordination, reflexes, tone. It was while examining his reflexes – a trifle abnormal on the left side – that the first bizarre experience occurred. I had taken off his left shoe and scratched the sole of his foot with a key – a frivolous-seeming but essential test of a reflex – and then, excusing myself to screw my ophthalmoscope together, left him to put on the shoe himself. To my surprise, a minute later, he had not done this.

‘Can I help?’I asked.

‘Help what? Help whom?’

‘Help you put on your shoe.’

‘Ach,’ he said, ‘I had forgotten the shoe,’ adding, sotto voce: ‘The shoe! The shoe?’ He seemed baffled.

‘Your shoe,’ I repeated. ‘Perhaps you’d put it on.’

He continued to look downwards, though not at the shoe, with an intense but misplaced concentration. Finally his gaze settled on his foot: ‘That is my shoe, yes?’

Did I mishear? Did he mis-see? ‘My eyes,’ he explained, and put a hand to his foot. ‘This is my shoe, no?’

‘No, it is not. That is your foot. There is your shoe.’

‘Ah! I thought that was my foot.’

Was he joking? Was he mad? Was he blind? If this was one of his ‘strange mistakes’, it was the strangest mistake I had ever come across.

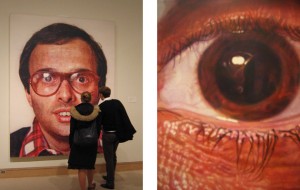

I helped him on with his shoe (his foot), to avoid further complication. Dr P. himself seemed untroubled, indifferent, maybe amused. I resumed my examination. His visual acuity was good: he had no difficulty seeing a pin on the floor, though sometimes he missed it if it was placed to his left.

He saw all right, but what did he see? I opened out a copy of the National Geographic Magazine, and asked him to describe some pictures in it. His eyes darted from one thing to another, picking up tiny features, as he had picked up the pin. A brightness, a colour, a shape would arrest his attention and elicit comment, but it was always details that he saw – never the whole. And these details he ‘spotted’, as one might spot blips on a radar-screen. He had no sense of a landscape or a scene.

I showed him the cover, an unbroken expanse of Sahara dunes.

‘What do you see here?’I asked.

‘I see a river,’ he said. ‘And a little guesthouse with its terrace on the water. People are dining out on the terrace. I see coloured parasols here and there.’ He was looking, if it was ‘looking’, right off the cover, into mid-air, and confabulating non-existent features, as if the absence of features in the actual picture had driven him to imagine the river and the terrace and the coloured parasols.

I must have looked aghast, but he seemed to think he had done rather well. There was a hint of a smile on his face. He also appeared to have decided the examination was over, and started to look round for his hat. He reached out his hand, and took hold of his wife’s head, tried to lift it off, to put it on. He had apparently mistaken his wife for a hat!•