Andrew Marantz’s New Yorker article, “Unreality Star,” is a brilliant piece that works as the perfect companion to Mike Jay’s excellent Aeon essay, “Reality Show,” as both study the intersection of paranoid psychotic disorders and our contemporary culture, which is truly saturated with surveillance. It doesn’t take much today to imagine we might be the unwitting stars of a beer commercial, a dating game, a reality show–because, in a sense, we all are. The opening:

Soon after Nick Lotz enrolled at Ohio University, in the fall of 2007, he grew deeply anxious. He was overweight, and self-conscious around women; worse, he thought that everyone sensed his unease. People who once seemed like new friends gradually stopped returning his texts. He went out four or five nights a week, and drank to mask his discomfort, occasionally to the point of blacking out. After such episodes, he worried that he’d said, or typed, something that he should have kept private. He suspected that people were posting embarrassing videos of him online, though he couldn’t find any on Facebook.

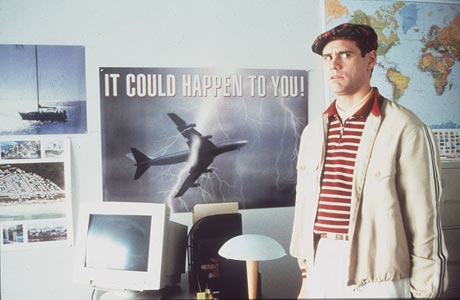

Lotz, who wanted to be a filmmaker, largely ignored his classwork. Often, he’d draw the blinds of his dorm room and take Suboxone, an opiate that he bought from an older student, and sleep for days. Then he’d snort Adderall or Focalin and stay up all night, watching YouTube videos and working on screenplays. His laptop became his primary connection to the world. Online interactions were less taxing than face-to-face conversations, but they introduced new concerns: just as he monitored his friends’ Internet activity, he assumed that, whenever he clicked links on BuzzFeed or posted comments on Reddit, people were tracking him, too. When he surfed the Web, in a sleepless blur, every site seemed to contain a coded message about him.•