Like Steve Jobs during his walkabout between stints as Apple’s visionary, Google’s Larry Page grew as a businessperson in the years he spent in the shadow of Eric Schmidt, the CEO whom investors forced him to hire as “adult supervision.” Although Page still has none of the late Apple co-founder’s charisma and communication skills, that social shortcoming might be a blessing some ways, since his vision of a future automated enough to satisfy Italo Balbo might give many pause, despite Page’s seemingly good intentions.

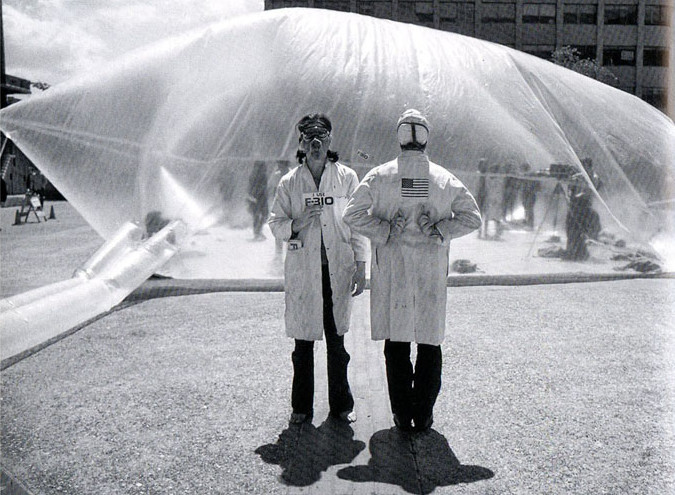

In 2013, he expressed his desire to partition some land to be used for potentially dangerous experiments that would otherwise be illegal. Like Burning Man with robots or flying cars or something. The Verge reported the technologist as saying:

There are many exciting things you could do that are illegal or not allowed by regulation. And that’s good, we don’t want to change the world. But maybe we can set aside a part of the world…some safe places where we can try things and not have to deploy to the entire world.•

His vision falls in line with H.G. Wells’ definition of Utopia as a place that would separate pristine living spaces from the despoiled, industrialized areas that would be exploited to support them.

It’s not a particularly honest or self-aware argument, however, because Google and other Silicon Valley superpowers are conducting experiments every day on the general public in regards to widespread surveillance, psychological manipulation and communications, all of which may be antithetical to stable democracies, the Internet being, what Schmidt himself termed that same year, the “largest experiment involving anarchy in history.” Indeed.

According a Statescoop article by Jake Williams, Google is moving forward with its plans to build Experiment City. Whatever explosions may occur in Page’s testropolis, they will likely be less dangerous than the eruptions the company is enabling every day in our “pristine” world.

An excerpt:

Sidewalk Labs, which Google kickstarted almost two years ago, may soon develop a “large-scale district” to serve as a living laboratory for urban innovation technologies, Dan Doctoroff, founder and CEO of the company, said at the Smart Cities NYC conference Thursday.

The company is having conversations now with city leaders across the country, Doctoroff said. While nothing is final, Sidewalk Labs could hold a competition — similar to the one held by the U.S. Department of Transportation last year — to spur excitement from leaders who want to make their cities smarter, while also providing a national model for what the cities of tomorrow look like.

“The future of cities lies in the way these urban experiences fit together and improve quality of life for everyone living, working and growing up in cities across the world,” Doctoroff said. “Yet there is not a single city today that can stand as a model — or even close — for our urban future.”

This city would be “built from the internet up,” Doctoroff said, and would test the theories and models that the company has asserted since its creation. …

While all these ideas include technology, the concept is about more than just connecting the physical space with sensors, internet and data, he said — it’s about making an impact on society.

“I’m sure many of you are thinking this is a crazy idea: building a city new — the most innovative, urban district in the world, something at scale that can actually have the catalytic impact among cities around the world,” Doctoroff said. “We don’t think it’s crazy at all. People thought it was crazy when Google decided to connect all the world’s information, people thought it was crazy to think about the concept of a self-driving car.”•