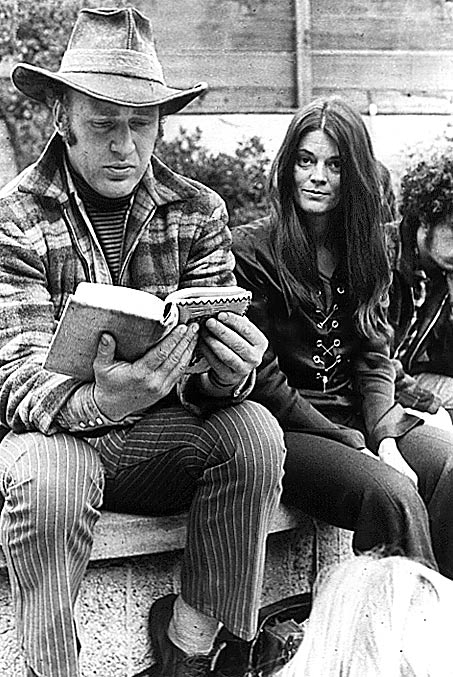

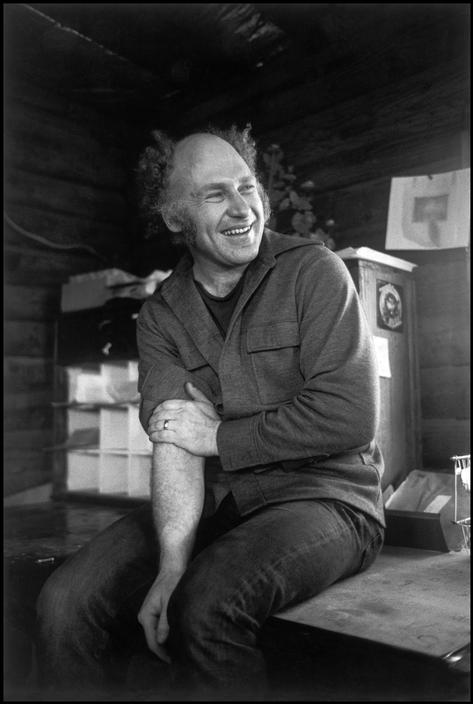

From “The Social History of the Hippies,” Warren Hinckle’s 1967 Ramparts article about those who tuned in, turned on and dropped out, a segment on writer Ken Kesey after his fall from grace with the younger longhhairs:

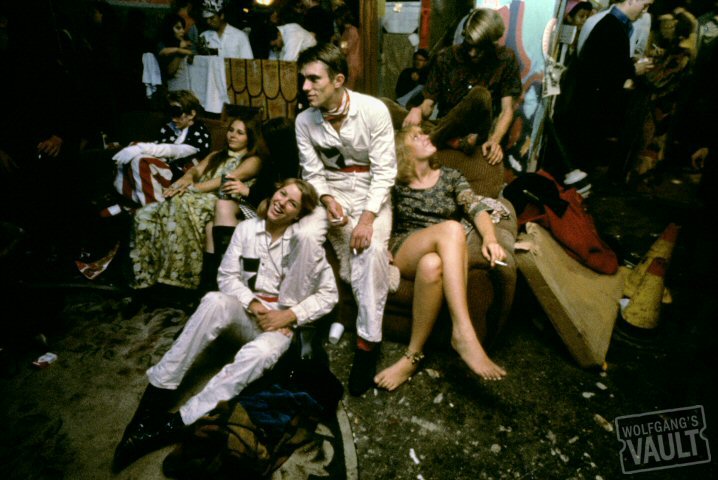

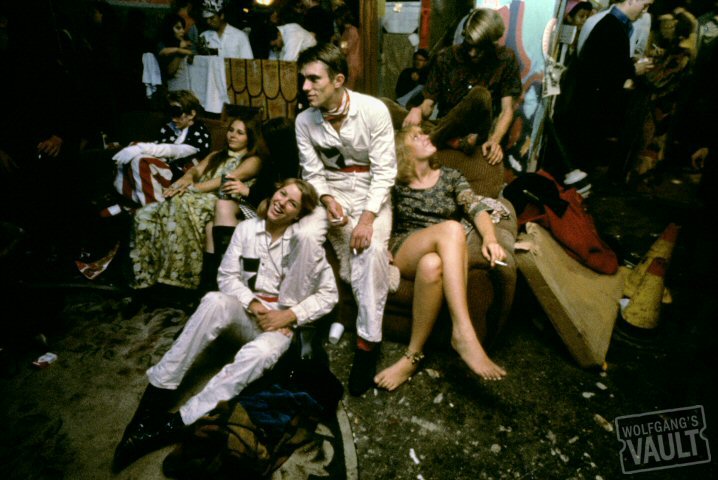

“HERE WASN’T MUCH DOING on late afternoon television, and the Merry Pranksters were a little restless. A few were turning on; one Prankster amused himself squirting his friends with a yellow plastic watergun; another staggered into the living room, exhausted from peddling a bicycle in ever-diminishing circles in the middle of the street. They were all waiting, quite patiently, for dinner, which the Chief was whipping up himself. It was a curry, the recipe of no doubt cabalistic origin. Kesey evidently took his cooking seriously, because he stood guard by the pot for an hour and a half, stirring, concentrating on the little clock on the stove that didn’t work.

There you have a slice of domestic life, February 1967, from the swish Marin County home of Attorney Brian Rohan. As might be surmised, Rohan is Kesey’s attorney, and the novelist and his aides de camp had parked their bus outside for the duration. The duration might last a long time, because Kesey has dropped out of the hippie scene. Some might say that he was pushed, because he fell, very hard, from favor among the hippies last year when he announced that he, Kesey, personally, was going to help reform the psychedelic scene. This sudden social conscience may have had something to do with beating a jail sentence on a compounded marijuana charge, but

when Kesey obtained his freedom with instructions from the judge ‘to preach an anti-LSD warning to teenagers’ it was a little too much for the Haight-Ashbury set. Kesey, after all, was the man who had turned on the Hell’s Angels.

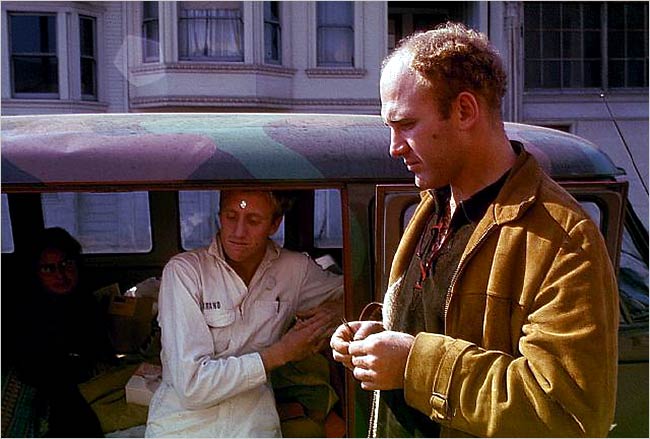

That was when the novelist was living in La Honda, a small community in the Skyline mountain range overgrown with trees and, after Kesey invited the Hell’s Angels to several house parties, overgrown with sheriff’s deputies. It was in this Sherwood Forest setting, after he had finished his second novel with LSD as his co-pilot, that Kesey inaugurated his band of Merry Pranksters

(they have an official seal from the State of California incorporating them as ‘Intrepid Trips, Inc.’), painted the school bus in glow sock colors, announced he would write no more (‘Rather than write, I will ride buses, study the insides of jails, and see what goes on’), and set up funtime housekeeping on a full-time basis with the Pranksters, his wife and their three small children (one confounding thing about Kesey is the amorphous quality of the personal relationships in his entourage—the several attractive women don’t seem, from the outside, to belong to any particular man; children are loved enough, but seem to be held in common).

When the Hell’s Angels rumbled by, Kesey welcomed them with LSD. ‘We’re in the same business. You break people’s bones, I break people’s heads,’ he told them. The Angels seem to like the whole acid thing, because today they are a fairly constant act in the Haight-Ashbury show, while Kesey has abdicated his role as Scoutmaster to fledgling acid heads and exiled himself across the Bay.

This self-imposed Elba came about when Kesey sensed that the hippie community had soured on him. He had committed the one mortal sin in the hippie ethic: telling people what to do. ‘Get into a responsibility bag,’ he urged some 400 friends attending a private Halloween party. Kesey hasn’t been seen much in the Haight-Ashbury since that night, and though the Diggers did succeed in getting him to attend the weekend discussion, it is doubtful they will succeed in getting the novelist involved in any serious effort to shape the Haight-Ashbury future. At 31, Ken Kesey is a hippie has-been.”