Timothy Leary had numerous odd experiences behind prison walls. There was the time he dropped acid with Massachusetts inmates, the one in which he shared a Folsom cellblock with Charles Manson and let us never forget the time he was lectured in the pen by friend Marshall McLuhan. Such was the life of the LSD salesman.

One of the few trips Leary never got to take, except posthumously, was a trek to outer space. In 1976, during his “comeback tour” after stays in 29 jails and a retirement of sorts, Leary dreamed of leaving it all behind–way behind. The opening of John Riley’s People article “Timothy Leary Is Free, Demonstrably in Love and Making Extraterrestrial Plans“:

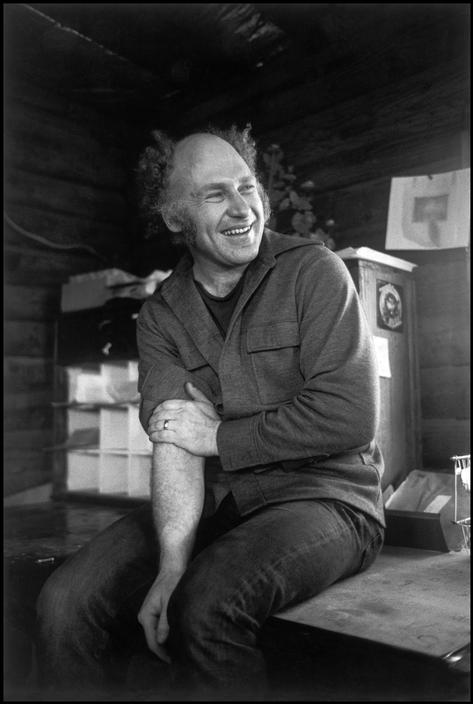

High in New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains, in a wood-heated A-frame beside a rushing stream, the retired guru speaks:

“After six years of silence, we have three new ideas which we think are fairly good. One is space migration. Another is intelligence increase. The third is life extension. We use the acronym SMI2LE to bring them together.”

The sage is Timothy Leary, high priest of the 1960s LSD movement, who is just four weeks out of the 29th jail he has inhabited since his first arrest in Laredo, Texas, 11 years ago. That charge was possession of less than half an ounce of marijuana that his then-wife, Rosemarie, had handed to his daughter. In recent months, when Leary was appearing before federal grand juries investigating the Weather Underground, he was moved from prison to prison for his own safety. Now paroled at age 56, he will soon start a term of probation whose length will be set by a federal judge.

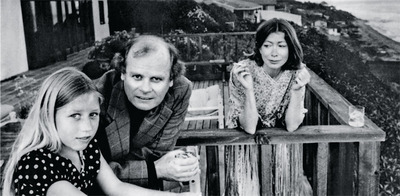

Leary fled a federal work camp in California in 1970, an escape planned by Rosemarie and the Weather Underground. The Learys went first to Africa, then to Switzerland, where their marriage collapsed. Leary met and was captivated by a then 26-year-old jet-setter, Joanna Harcourt-Smith, whom he married in 1972. Three weeks later they traveled to Afghanistan, where U.S. authorities captured them both and flew them back to Los Angeles.

“Joanna visited me regularly,” Leary says. “She published several of my books and lobbied and schemed to get me free.” He looks at her adoringly, and she turns from the breakfast dishes in the sink to kiss him. Joanna tells how she collared Betty Ford on a street in San Diego and pleaded with her for Tim’s freedom. “I’m doing for my husband what you’re doing for yours. You’re helping yours get elected President, and I’m helping mine get out of prison.”

“One of the plans that she was continually hatching to break me out,” says Leary, “was for her to descend onto the Vacaville prison grounds in a silver helicopter blaring Pink Floyd music, wearing nothing but a machine gun. We called it Plan No. 346.”

“You know,” he continues, after Joanna has left to drive to a village 10 miles away for groceries and cigarettes, “in 1970 the U.S. government directly and bluntly shut me up. It was the greatest thing that could have happened, because I had run out of ideas.” His face, its prison pallor turned to brown by the mountain sun, breaks into a grin. A woodpecker hammers at the chimney of their Franklin stove. “Does that every morning,” says Leary. “We’ve named him the tinpecker.

“Well, SMI2LE, as I said, is a good idea. The acronym is woven into Joanna’s belts and purses. The space migration part is what I’m working on right now. Los Alamos [the atomic laboratory] is not far away and I have lots of questions about laser fusion. And this valley is an ideal temporary planetary base of operations for getting away from earth.”

Leary not only wants to live on a space station between the earth and the moon, he wants to take some of the planet with him. “How far can we see from here?” he asks. “Half a mile? According to a professor at Princeton, such an area could be compressed to a degree that I figure could be fit within a NASA spacecraft.”•