Last year, Mike Jay wrote a great essay for Aeon about people being driven to paranoia by the omnipresence of technology, but fear of “influence machines” stretches back much further than the information-sucking Internet. In a Public Domain Review piece, the same writer looks at the curious case of James Tilly Matthews, the first-recorded sufferer of paranoid schizophrenia, who believed in the 1790s that his mind–and the whole mad world–had fallen under the sway of a contraption called the “Air Loom.” It’s a subject Jay knows well. The opening:

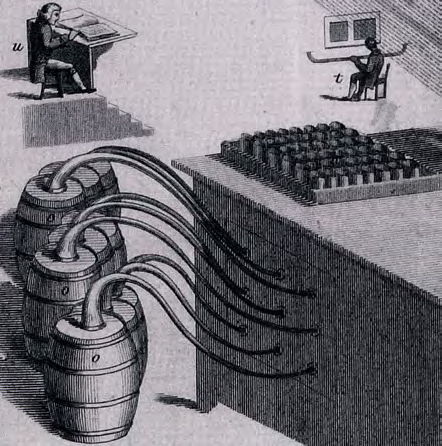

“In 1810 John Haslam, a London apothecary, published the first ever book-length description of a mad person’s delusions. Until this point most medical case histories of what we now refer to as mental illness had amounted to a line or two at most, and more often just a single word such as ‘frenzied’ or ‘melancholy.’ But the opinions of James Tilly Matthews resisted any such summary. He described a previously unimagined world of futuristic machines, ‘magnetic spies’ and mass brainwashing, woven into a bizarre but undeniably well-informed narrative of the high politics behind the Napoleonic Wars.

Haslam titled his book Illustrations of Madness, and it was full of lessons for the nascent profession of ‘mad-doctoring,’ later to be known as psychiatry. But it was also written to settle a personal score. Haslam was the apothecary at the Royal Bethlem Hospital – in popular slang, Bedlam – where James Tilly Matthews had for the previous decade been confined as an incurable lunatic. Not everyone, however, believed that Matthews was mad. Haslam’s diagnosis had been contested by other doctors, and the governors of Bethlem had distanced themselves from it. He wrote his book in retaliation against his superiors; but as it turned out, his patient would have the last word.

Although Haslam has been relegated to a footnote in the history of psychiatry, his account of Matthews’ inner world is still cited as the first fully described case of what we now call paranoid schizophrenia, and in particular of an ‘influencing machine’: the belief, or delusion, that a covertly operated device is acting at a distance to control the subject’s mind and body. For everyone who has since had messages beamed at them by the CIA, MI5, Masonic lodges or UFOs, via dental fillings, mysterious implants, TV sets or surveillance satellites, James Tilly Matthews is patient zero.”