Jeez, Jim Holt is a dream to read. If you’ve never picked up his 2012 philosophical and moving inquiry, Why Does the World Exist?: An Existential Detective Story, it’s well worth your time. For awhile it was cheekily listed No. 1 at the Strand in the “Best Books to Read While Drunk” category, but I don’t drink, and I adored it.

In a 2003 Slate article, “My Son, the Robot,” Holt wrote of Bill McKibben’s Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age, a cautionary nonfiction tale that warned our siblings soon would be silicon sisters, thanks to the progress of genetic engineering, robotics, and nanotechnology. It was only a matter of time.

Holt was unmoved by the clarion call, believing human existence unlikely to be at an inflection point and thinking the author too dour about tomorrow. While Holt’s certainly right that we’re not going to defeat death anytime soon despite what excitable Transhumanists promise, both McKibben and the techno-optimists probably have time on their side.

An excerpt:

Take McKibben’s chief bogy, genetic engineering—specifically, germline engineering, in which an embryo’s DNA would be manipulated in the hopes of producing a “designer baby” with, say, a higher IQ, a knack for music, and no predisposition to obesity. The best reason to ban it (as the European Community has already done) is the physical risk it poses to individuals—namely, to the children whose genes are altered, with unforeseen and possibly horrendous consequences. The next best reason is the risk it poses to society—exacerbating inequality by creating a “GenRich” class of individuals who are smarter, healthier, and handsomer than the underclass of “Naturals.” McKibben cites these reasons, as did Fukuyama (and many others) before him. However, what really animates both authors is a more philosophical point: that genetic engineering would alter “human nature” (Fukuyama) or take away the “meaning” of life (McKibben). As far as I can tell, the argument from human nature and the argument from meaning are mere terminological variants of each other. And both are woolly, especially when contrasted with the libertarian argument that people should be free to do what they wish as long as other parties aren’t harmed.

Finally, McKibben’s reasoning fitfully betrays a vulgar variety of genetic determinism. He approvingly quotes phrases like “genetically engineered thoughts.” Altering an embryo’s DNA to make your child, say, less prone to violence would turn him into an “automaton.” Giving him “genes expressing proteins to boost his memory, to shape his stature” would leave him with “no more choice about how to live his life than a Hindu born untouchable.” Why isn’t the same true with the randomly assigned genes we now have?

Now to the deeper fallacy. McKibben takes it for granted that we are at an inflection point of history, suspended between the prehistoric and the Promethean. He writes, “we just happen to be alive at the brief and interesting moment when [technological] growth starts to really matter—when it spikes.” Everything is about to change.

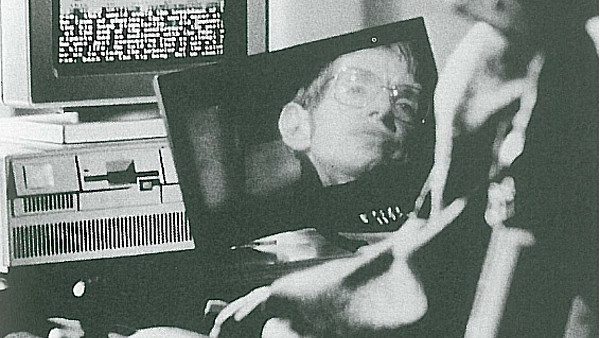

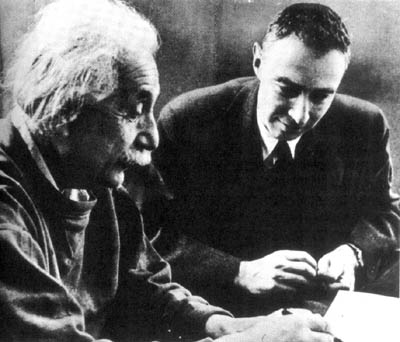

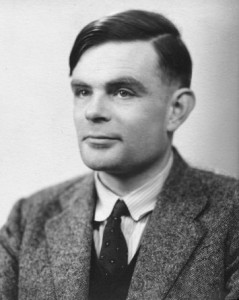

The extropian visionaries arrayed against him—people like Ray Kurzweil, Hans Moravec, Marvin Minsky, and Lee Silver—agree. In fact, they think we are on the verge of conquering death (which McKibben thinks would be a terrible thing). And they mean RIGHT NOW. When you die, you should have your brain frozen; then, in a couple of decades, it will get thawed out and nanobots will repair the damage; then you can start augmenting it with silicon chips; finally, your entire mental software, and your consciousness along with it (you hope), will get uploaded into a computer; and—with multiple copies as insurance—you will live forever, or at least until the universe falls apart.•