An indicator of how far we’ve fallen and how much further we might plummet is a pair of really talented New York Times journalists having a casual conversation about Donald Trump potentially using the office of the Presidency to punish private companies that haven’t been “nice” to him and neither one mentioning how unethical that is and how chilling for a democracy. You could say perhaps that goes without saying, but it seems like we’ve already accepted what should never be acceptable.

The excerpt:

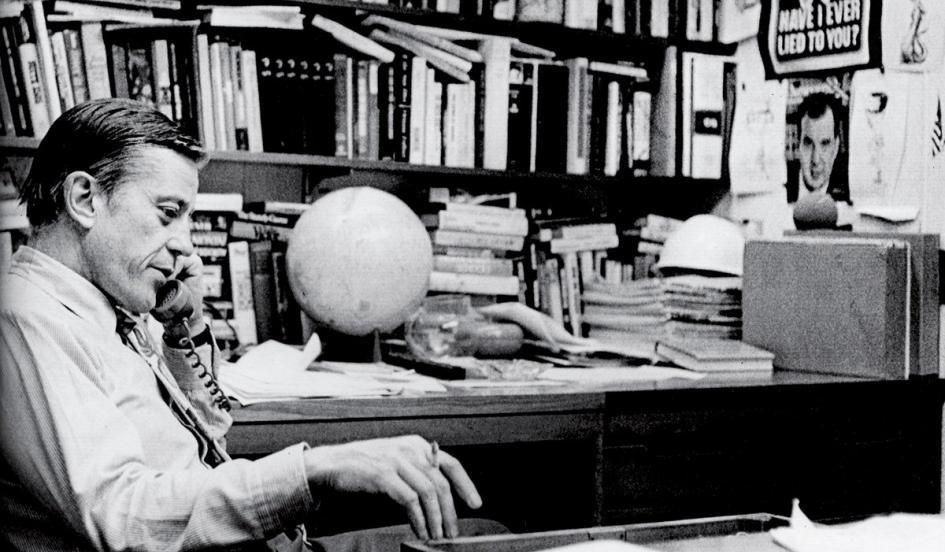

Farhad Manjoo:

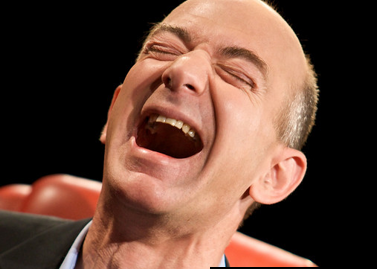

Amazon put out a statement promising to create 100,000 new full-time jobs in the United States over the next year and a half. The company did not mention Trump, but the statement seemed as if it was part of a pattern of corporations sending out good news to the incoming president. A half-dozen companies, including Ford and SoftBank, have promised to hire more American workers. As with the others, though, it’s not quite clear if Amazon’s promises are a deviation from its plans, or if it’s just pre-announcing growth that was already baked in.

Mike Isaac:

Is it cynical for me to say “the latter”? Seems like a pretty obvious way to curry favor with the new boss while just doing what you were already planning to do.

Farhad Manjoo:

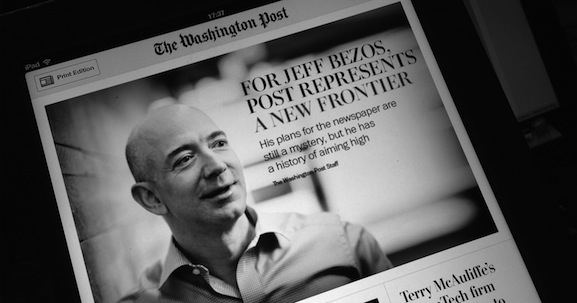

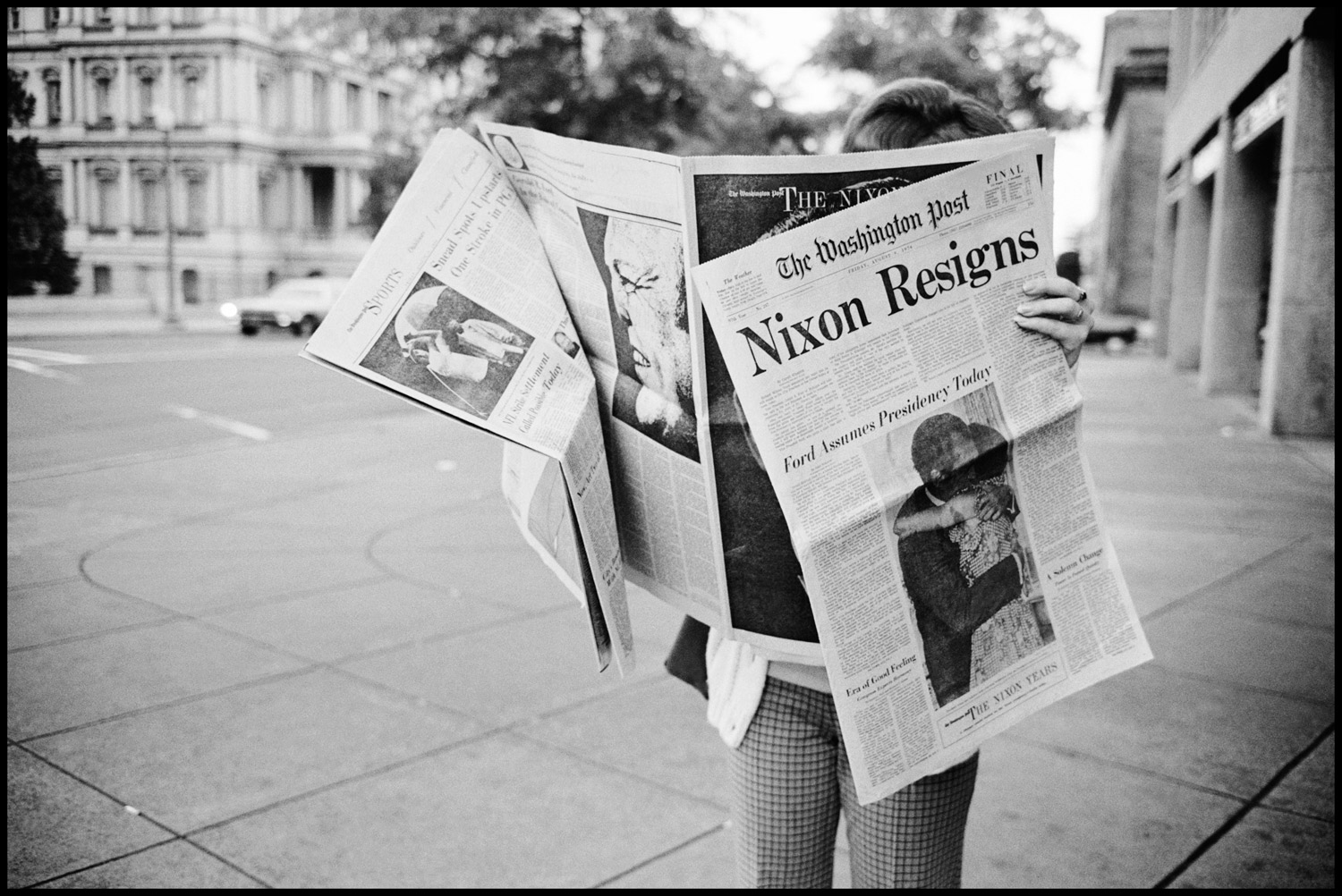

Well, analysts also believe it’s the latter — Trump or no Trump, Amazon is growing really quickly, so it most likely had plans to hire all these people anyway. But Trump has had Amazon in his sights for a while; during the campaign he frequently threatened the company with antitrust action, often in response to critical coverage from The Washington Post, which Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, owns. In that light, Amazon’s job announcement is a savvy defense: Come after us and you’ll come after all these new jobs. Do you think it’s going to work?

Mike Issac:

Honestly, I’m not sure, but if experience tells us anything about Trump’s actions, it is this: Compliment the guy or win him over, and he’ll be your new best friend. Cross him, and prepare for a gnarly tweetstorm. He’s about as mercurial as a thermometer, so there’s no real road map for predicting his actions outside of seeing who has wooed him most recently.

Farhad Manjoo:

Agreed.•