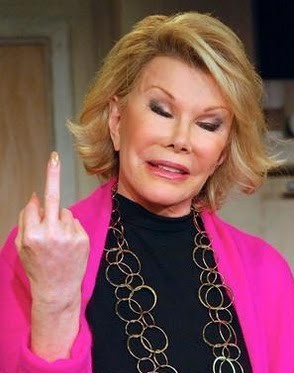

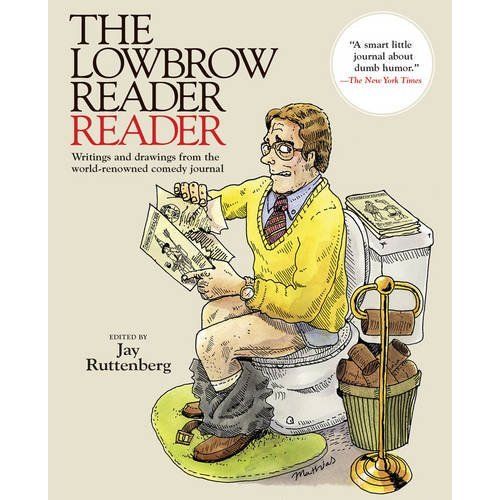

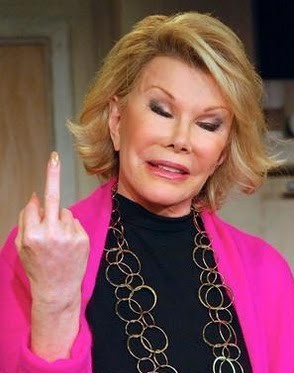

When I posted a piece from Jay Ruttenberg’s new Gilbert Gottfried article, it reminded me of his excellent 2007 profile of the recently deceased Joan Rivers for HEEB magazine. I would have linked to it earlier, but I had no idea it was online and ungated. If you were perplexed by the level of attention the comic’s protracted passing received, thinking she was just some mean and tacky lady, this piece will explain it to you. It’s one of the most insightful things I’ve ever read about her–or any comic. Rivers continued to do tiny shows in NYC spaces even after tremendous fame and wealth because she thought of comedy as a mission, as a palliative, even if the medicine was rough on the way down. She wasn’t playing small venues to hone material for more important gigs. These performances weren’t a means, they were an end. Every moment was important. An excerpt follows.

________________________________

Joan lives in the penthouse of an old limestone building in the lower regions of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, seconds from the park and, perhaps of greater importance, Bergdorf Goodman. The building was designed by Horace Trumbauer, architect of the gilded age; Ernest Hemingway once lived there. It has all the ostentation you would expect: an old-fashioned elevator with its own operator, ornate walls emblazoned with the type of gold trim traditionally favored by European monarchs, a book-filled library with a blazing fireplace and a stray piece of mink flopped across the sofa. Yet her duplex has a bright, loud vibe not in keeping with its grandeur. Phones ring incessantly, assistants converse in the background, her dogs race about and the help kibitz with their employer about their mutual affinity for The Sarah Silverman Program. On her sofa lies a needlepoint pillow reading, “I need a man to spoil me or I don’t need a man at all.”

Rivers has been busy. The previous evening, she flew into New York from a road gig and went straight from the airport to the Cutting Room. The comic was a fright from the plane, so her hairdresser met her at the club and fixed her up in the dingy hallway backstage. Hours later, she woke up and appeared on Martha Stewart Living, which she claims to love going on “because I take all her hors d’oeuvres home.” Without changing from the puffy red outfit she wore on Martha, Rivers retreated to her office and wrote real estate jokes in preparation for a corporate gig that evening for The Corcoran Group. When Joan says “Corcoran Group,” she employs the mocking tone one might use to send up the Prince of Wales. “They said to me, “We don’t want anything blue,’” Rivers rasps. “I love when they use the term ‘blue,’ because that tells you they’re over 35. I said, ‘Have you got the wrong chick.’”

She was disappointed with her previous night’s Cutting Room performance. “I had just come off a show that was so spectacular, and the audience wasn’t as good as the night before,” she says. “I mean, they didn’t know they weren’t good. They thought they had a terrific show. But I walked off and thought, ‘Achhh.’” Rivers starts cackling, as she does whenever she is about to say something inappropriate. “I started the night talking about 9/11,” she says, still laughing. “I hadn’t even warmed them up. That was my first subject. It was like, ‘Hello, good evening—so, who do you wish had died?’ There was a lot of gasping.”

The bit Rivers is referring to is among her most vicious. It finds her lowering her voice to a conspiratorial whisper and asking her crowd, “If you knew what was going to happen on September 11th, who would you invite to breakfast at the World Trade Center? ‘Eggs benedict…Windows on the World… It’ll be our make-up brunch!’” Week in and week out, the funniest part of the joke isn’t the punch line so much as Rivers’ indignation when the audience falls silent. “Oh look at this room!” she’ll yell. “What are you, a bunch of Christians? You’re telling me there aren’t people you want to see dead? I could give you a list a mile long!”

On a good night, somebody might boo; on a great night, a person will walk out. “Somebody should be upset,” Rivers contends. “If you’re a comedian and people think, ‘Oh, she’s so nice,’ then what are you doing? You’re not contributing anything. Comedians are there to shake people up and make them face the truth. Because if you face the truth, you can get through anything.”