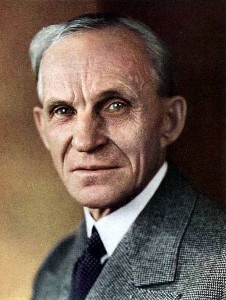

Speaking of bigoted public businessmen, not even the Andrew “Dice” Jackson currently in the White House could hold a taillight to Henry Ford, who was such a virulent anti-Semite that he actually published a newspaper to disseminate his hateful views. The Model-T magnate purchased the Dearborn Independent in 1919, and until it was sued out of existence eight years later, he helped to fan the flames of intolerance that eventually led to the greatest tragedy of the twentieth century. At least, though, he never became President.

Retro racism isn’t the only aspect of Ford’s worldview that’s ascendant once more. Like today’s Libertarian sea-steaders and deep-pocketed New Zealand zealots, the industrialist dreamed of skirting rules and regulations and building a haven according to his narrow worldview far from the madding crowd. Fordlândia, as he modestly called it, was established in 1928 in the Amazon Rainforest to create a cheap supply of rubber for automobile parts.

It wasn’t long before the locals hired for the project bristled under the incredibly severe lifestyle requirements laid down by the plutocrat. Open revolt began. These uprisings and poor planning ultimately forced the settlement into failure by 1934, when it was abandoned.

From Simon Romero in the New York Times:

From the start, ineptitude and tragedy plagued the venture, meticulously documented in a book by the historian Greg Grandin that I read on the boat as it made its way up the Tapajós. Disdainful of experts who could have advised them on tropical agriculture, Ford’s men planted seeds of questionable value and let leaf blight ravage the plantation.

Despite such setbacks, Ford constructed an American-style town, which he wanted inhabited by Brazilians hewing to what he considered American values.

Employees moved into clapboard bungalows — designed, of course, in Michigan — some of which are still standing. Streetlamps illuminated concrete sidewalks. Portions of these footpaths persist in the town, near red fire hydrants, in the shadow of decaying dance halls and crumbling warehouses.

“It turns out Detroit isn’t the only place where Ford produced ruins,” said Guilherme Lisboa, 67, the owner of a small inn called the Pousada Americana.

Beyond producing rubber, Ford, an avowed teetotaler, anti-Semite and skeptic of the Jazz Age, clearly wanted life in the jungle to be more transformative. His American managers forbade consumption of alcohol, while promoting gardening, square dancing and readings of the poetry of Emerson and Longfellow.

Going even further in Ford’s quest for utopia, so-called sanitation squads operated across the outpost, killing stray dogs, draining puddles of water where malaria-transmitting mosquitoes could multiply and checking employees for venereal diseases.

“With a surety of purpose and incuriosity about the world that seems all too familiar, Ford deliberately rejected expert advice and set out to turn the Amazon into the Midwest of his imagination,” Mr. Grandin, the historian, wrote in his account of the town.

These days, the ruins of Fordlândia stand as testament to the folly of trying to bend the jungle to the will of man.•