Trump will eventually be flushed down the vortex along with other waste products swirling around him, I’m fairly certain at this point, but as an amateur student of human psychology I’d be fascinated to know if he’s fully wrapped his declining brain around this scenario. Is it within his mental powers to grasp that some combination of potential financial crimes, traitorous activity and obstruction of justice could end up with him laundering prison clothes rather than money? As I’ve mentioned, I don’t think America is saved when Trump is toppled, but his ouster is necessary if we’re to have a chance to rescue our Republic and reform our government. Or maybe we’ll end up in another Civil War. Either or.

Trump will eventually be flushed down the vortex along with other waste products swirling around him, I’m fairly certain at this point, but as an amateur student of human psychology I’d be fascinated to know if he’s fully wrapped his declining brain around this scenario. Is it within his mental powers to grasp that some combination of potential financial crimes, traitorous activity and obstruction of justice could end up with him laundering prison clothes rather than money? As I’ve mentioned, I don’t think America is saved when Trump is toppled, but his ouster is necessary if we’re to have a chance to rescue our Republic and reform our government. Or maybe we’ll end up in another Civil War. Either or.

Elizabeth Drew, the great correspondent of the Watergate Era, cautions that any Trump impeachment process must be a gradual and bilateral one. Of course, we live in a faster age and a far more divided one, so I don’t know if that’s possible. It’s not that I don’t think McConnell and Ryan and the rest wouldn’t kick a sad old goat from a cliff to save their own hides, but I’m not sure that if Russian collusion is proved that it doesn’t pull way more Republicans over the precipice than we can currently guess. The GOP will fight such an outcome with all it has.

In a New York column about Trump’s possible ouster, Frank Rich cites Drew’s work and compares the slow-forming Watergate inferno to the fire next time. An excerpt:

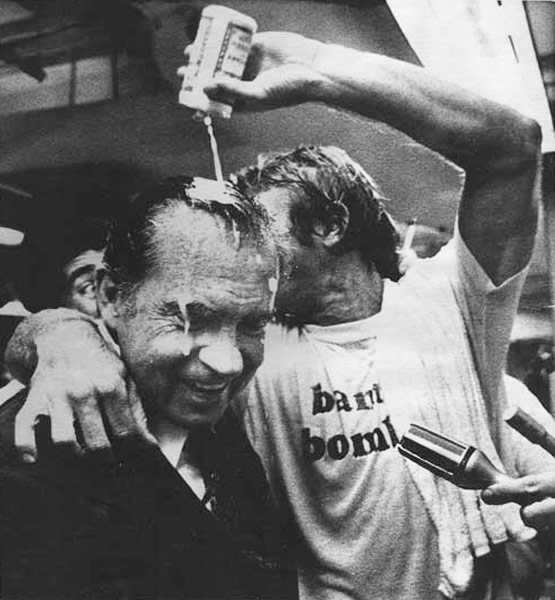

Here’s Drew describing a typical Watergate day: “The news is coming too fast. Faster and harder than anyone expected. It is almost impossible to absorb.” And here she is a week after Nixon’s vice-president, Spiro Agnew, resigned upon pleading no contest to charges of bribery and tax fraud: “The city seems to be reeling around amidst the events and the breaking stories. In the restaurants, the noise level is higher. At the end of the day, someone says, ‘It’s like being drunk.’ ” It already feels like that right now.

One could argue that the context is different today — that the America of 2017 is not the America of the early 1970s. We think of our current culture as being harder to shock, easier to distract, and more inured to crude public figures who violate traditional societal norms as unabashedly as Trump. This, in theory, would make him harder to dislodge than Nixon, whose sins would more easily scandalize a relatively innocent 20th-century citizenry. But even without the internet’s cacophony, Nixon faced a post-1960s America as factionalized, jaded, and accustomed to shock as our own: It had witnessed the assassination of two Kennedys and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a complete overhaul of its mores as a consequence of a rising counterculture and women’s movement, and a domestic civil war precipitated by the catastrophe of Vietnam. The alarming toxicity of Trump has burst through the noise of our America much as Nixon’s did through his. And while the technology for delivering news makes it come faster and harder in 2017 than Drew or any of us could have anticipated in that day of daily newspapers and nightly news broadcasts, the onslaught of shocking developments felt no less overwhelming then than now.

Human nature hasn’t changed — not for those of us standing outside a teetering White House or for the cast of characters within. Much as Trump risked his presidency by empowering hotheaded ideologues like Michael Flynn and Steve Bannon, so Nixon’s White House had recruited the similarly reckless G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt to wage war on the president’s perceived enemies. As John A. Farrell writes in his new, state-of-the-art Richard Nixon: The Life, both of them were “wannabe James Bonds.” Hunt, an alumnus of the CIA’s Bay of Pigs fiasco, was the prolific author of often pseudonymous spy novels, while Liddy was alt-right before it was cool: “a right-wing zealot, with a fixation for Nazi regalia and a kinky kind of Nietzschean philosophy,” who “organized a White House screening of the Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will.”

Though there are a number of areas where the Nixon and Trump narratives diverge, in nearly every case Trump’s deviations from the Watergate model make it even less likely that he will survive his presidency.•