During the darkest days of the second Bush Administration, the comedian Lewis Black had a great joke about hoping for the first time in his life that there would be a military coup in America. The politicians were so bad that the generals were clearly preferable.

At the center of the Army’s appeal stood David Petraeus, a talented commander who was built to mythical proportions out of political expedience, so that a President who’d lost the faith of the people could still operate abroad militarily. But his surge did not last. Like most heroes of convenience, the general was bound for a fall, but the extent of his defeat and surrender was shocking. Scandals personal and professional ended his brilliant career, even if he managed to avoid prison time.

The former CIA Director, now building equity on Wall Street, sat down for lunch with the Financial Times’ Edward Luce, who’s done some of the best writing on American politics during this crazy election year. The journalist finds a subject who doesn’t seem given to deep self-analysis despite his precipitous fall from grace. The opening:

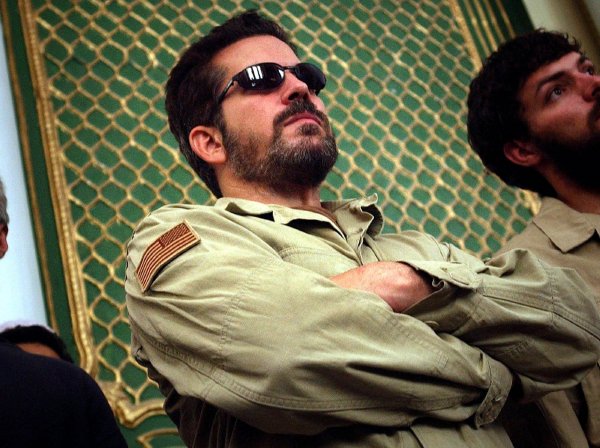

On the dot of noon, as agreed, General David Petraeus strolls into the Four Seasons Restaurant. His arrival causes a flurry among the floor staff. Dressed in a navy blue suit and plain red tie, the former CIA chief is businesslike — in keeping with his new role on Wall Street. When I inquire what keeps him busy nowadays his answer goes on for so long I half regret asking. In addition to a lucrative job in private equity and a clutch of teaching jobs, he is “on the [paid] speaking circuit.” Chuckling, and in an apparent reference to Bernie Sanders’ attacks on Hillary Clinton’s gilded speaking career, he adds: “Many have noted it is the highest form of white-collar crime.” Only when I touch on the scandal that ended his meteoric public career does he assume a crisper tone.

Just four years ago, Petraeus was lionised as the Douglas MacArthur of his generation. Even discounting the hype, he stood head and shoulders above other US generals. In the depths of the Iraq war, when the country was undergoing death by a thousand improvised explosive devices, he was dubbed “King David” of Mosul — a city he cleared and held before it fell back into rebel hands. He was then appointed chief architect of George W Bush’s 2007 Iraq surge and, after a stint as head of the Pentagon’s Central Command, Barack Obama put him in charge of his own surge in Afghanistan. His reward was to be made head of the Central Intelligence Agency in 2011. Many thought the CIA was a springboard for Petraeus’s own presidential ambitions. America loves a successful general and his approval ratings were stratospheric. Could anything stand in his way?

The answer was yes — David Petraeus himself. Shortly after Obama’s re-election in 2012, Petraeus abruptly resigned from the CIA when it emerged he had shared eight notebooks of classified information with his biographer, Paula Broadwell. They had also had an affair. Rarely has a fall from grace been so brutal.•