When you continually appeal to the margins, that’s where you end up. The GOP found the radicals and paranoiacs in their midst useful for a good while. The Reagan, Gingrich and Limbaugh surges were built on pandering to those with rigid feelings about race, religion and rights. In the early days of coded language and manipulation, the Republicans were still about winning governance and trying to do something with it. But the ante was gradually upped, the most fervent of the loyalists they’d cultivated demanded it, the discourse grew vicious, and disdain for government born in the public consciousness during the Reagan years became a full-grown monster. Now the party is a Frankenstein supported by a torch-carrying mob.

David Brooks’ opinions in the NYT often appall me, but in his latest column he sums up the party’s slow passage into insanity, how the sideshow moved to the center ring, better and more succinctly than anyone on the Left or Right has. An excerpt:

By traditional definitions, conservatism stands for intellectual humility, a belief in steady, incremental change, a preference for reform rather than revolution, a respect for hierarchy, precedence, balance and order, and a tone of voice that is prudent, measured and responsible. Conservatives of this disposition can be dull, but they know how to nurture and run institutions. They also see the nation as one organic whole. Citizens may fall into different classes and political factions, but they are still joined by chains of affection that command ultimate loyalty and love.

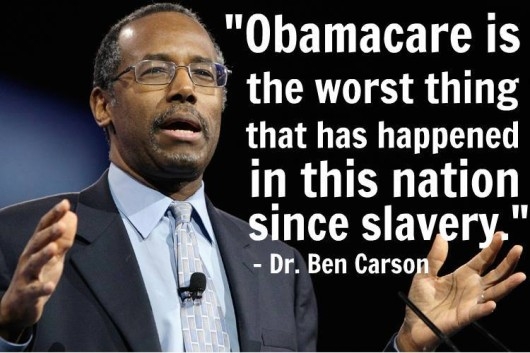

All of this has been overturned in dangerous parts of the Republican Party. Over the past 30 years, or at least since Rush Limbaugh came on the scene, the Republican rhetorical tone has grown ever more bombastic, hyperbolic and imbalanced. Public figures are prisoners of their own prose styles, and Republicans from Newt Gingrich through Ben Carson have become addicted to a crisis mentality. Civilization was always on the brink of collapse. Every setback, like the passage of Obamacare, became the ruination of the republic. Comparisons to Nazi Germany became a staple.•