A secondary problem of pathological liars is that occasionally they are telling the truth, but who would know? Believing them will usually get you into trouble, and every now and then so will not believing them. If the President, the person entrusted with our security, is that incessant fabricator, the confusion and peril can become lethal.

The current Administration’s brazen dishonesty and fumbling attempts at cover-ups would not be an existential threat to our democracy were it healthy, but the vital signs have been worrying for over two decades. Trump’s ascension feels more like the other shoe dropping than the first swift kick.

Our populace and politicians are sharply divided along partisan lines, the GOP so deeply dysfunctional, that the Republican-led legislature is now endeavoring to obfuscate in his favor despite seemingly traitorous behaviors, perhaps even treasonous ones, while a good percentage of Americans wouldn’t care if it was proven his campaign conspired with the Kremlin to steal the White House. And the truth only matters if it’s valued.

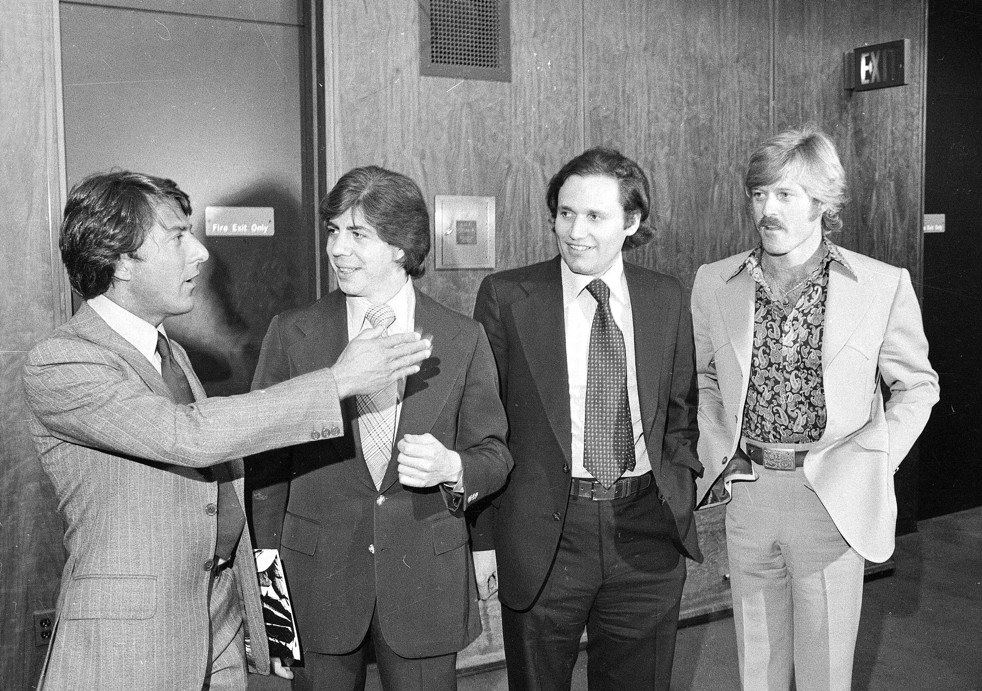

In a Huffington Post essay about transparency, that quaint, hoary thing, philosopher Daniel Dennett is confident that Trump will eventually choke on his lies. Robert Redford, who has, of course, a strong link to Nixon’s waterloo, isn’t so sure our system today is quite that fail-safe, as he writes in an op-ed in the Washington Post. Deep Throats can talk all day but it won’t matter if too many people aren’t listening.

Two excerpts follow.

From Dennett:

Leaders, democratic just as much as autocratic, need to keep secrets if they are going to be effective. There is an obvious reason why the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics keeps its new employment rate statistics and other economic indicators secret until a precise moment when everybody gets to learn them at the same time.

But leaders also need to be trusted when they make statements, promises and denials. They can’t divulge too much and they can’t lie too much. Very often saying nothing is the best policy, for obvious reasons, but they must also communicate often with both their people and their opponents. So as far as I know, nobody has ever devised a formula or recipe for how much to communicate and when. We want leaders we can trust, but we also want to trust them to keep secrets when it is in our interest to do so. The problem is, not all leaders understand the nuance.

U.S. President Donald Trump is one of them. The leader of the free world apparently has no concern for his credibility. He is constantly caught in demonstrable falsehoods, which he never acknowledges and for which he never apologizes. And his supporters seem all too willing to say they believe his whoppers, or just forgive him, or even applaud his disruption of ambient trust. But what will happen when he gets caught telling them whoppers about what he is doing for them? He will be tempted, of course, to pile on more lies in order to get out of his tight spot, but a rich vein of wisdom running through all the lore and literature of the world is that such lying cannot be shored up indefinitely with more lying.

Eventually, the truth overpowers the lies and the result is ruin. Trump seems to be unaware of this. He seems to be like the gambler who thinks that by just doubling his bets he’s bound to regain his losses eventually. We know that this is a fallacy; sooner or later he will run out of allies, time or money. We just don’t want to be victims along with Trump when his house of cards collapses, as it will.•

From Robert Redford in the Washington Post:

When President Trump speaks of being in a “running war” with the media, calls them “among the most dishonest human beings on Earth” and tweets that they’re the “enemy of the American people,” his language takes the Nixon administration’s false accusations of “shoddy” and “shabby” journalism to new and dangerous heights.

Sound and accurate journalism defends our democracy. It’s one of the most effective weapons we have to restrain the power-hungry. I always said that All the President’s Men was a violent movie. No shots were fired, but words were used as weapons.

In fact, I had a hard time getting producers interested in All the President’s Men. “Newspapers, typing, journalism — there’s no drama here” — so the critique went. I didn’t see it that way. To me it was a story about two journalists hell-bent on getting to the truth. That’s the movie, but the real-life Watergate scandal didn’t have just two people searching for the truth. It had an entire cast of characters in minor and major roles who followed their consciences: President Richard Nixon’s counsel John Dean, whose testimony blew open the congressional hearings; Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus, who both resigned rather than follow Nixon’s demand to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox; and, most of all, congressional Democrats and Republicans.

Nixon resigned from office because the Senate Watergate Committee — its Democratic and Republican members — did its job. It’s easy now to think of Watergate as a single event. It wasn’t; it was a story that unfolded over 26 months and demanded many acts of bravery and honesty by Americans across the political spectrum.

The system worked. The checks and balances the Constitution was designed to create functioned when put to their biggest test. Would they still? Which brings me to the other half of the question: What’s different now?

Much.•