The names Benjamin Franklin and Jenny McCarthy don’t usually squeeze into the same sentence, but they did both make a similar stand 290 years apart: They were anti-Vaxxers.

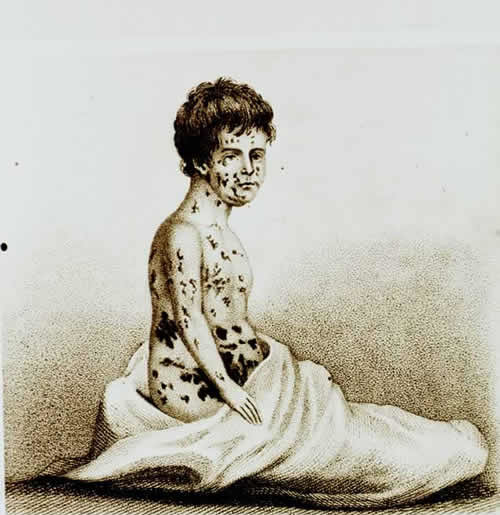

We know well of the blonde celebrity’s inane crusade linking vaccinations and autism, but America’s key-and-kite man similarly stood strong against smallpox inoculations in the early 1700s. Just as confounding was that the witch-burning enabler Cotton Mather was on the right side, spearheading the successful experiment which provoked violent dissent. The caveat is that Franklin was a mere 16 at the time, though it does remind that we all need to constantly question our beliefs despite our intellects or qualifications or allegiances.

Mike Jay, a wonderful thinker (see here and here and here) has written about this strange moment in history in a WSJ book review of Stephen Coss’ The Fever of 1721, which looks at how this roiling controversy anticipated aspects of the American Revolution. An excerpt:

Inoculation was commonplace across swaths of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, Mr. Coss explains, but this inclined the doctors of Enlightenment-era Europe to regard it as a primitive superstition. Such was the view of William Douglass, the only man in Boston with the letters “M.D.” after his name, who was convinced that “infusing such malignant filth” in a healthy subject was lethal folly. The only person Mather could persuade to perform the operation was a surgeon, Zabdiel Boylston, whose frontier upbringing made him sympathetic to native medicine and who was already pockmarked from a near-fatal case of the disease.

“Given that attempting inoculation constituted an almost complete leap of faith for Boylston,” Mr. Coss writes, “he spent surprisingly little time agonizing over it.” He knew personally just how savage the toll could be. On June 26, 1721, just as the epidemic began to rage in earnest, Boyston filled a quill with the fluid from an infected blister and scratched it into the skin of two family slaves and his own young son.

News of the experiment was greeted with public fury and terror that it would spread the contagion. A town-hall meeting was convened, at Dr. Douglass’s instigation, at which inoculation was condemned and banned. Mather’s house was firebombed with an incendiary device to which a note was attached: “I will inoculate you with this.”

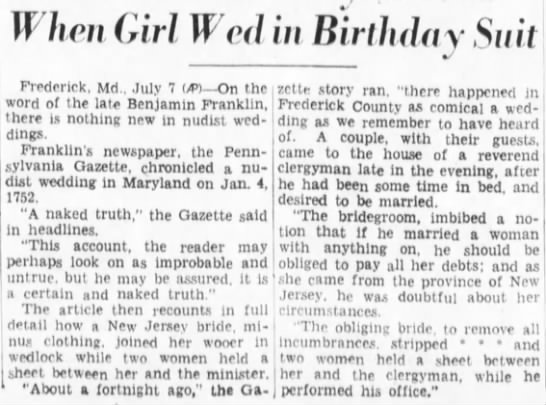

The crisis was the making of James and Benjamin Franklin’s New-England Courant, which stoked the controversy with denunciations of Mather that drew parallels between his “infatuation” with inoculation and his onetime obsession with witchcraft. But as the death toll mounted, the ban on inoculation collapsed under the weight of public demand.•