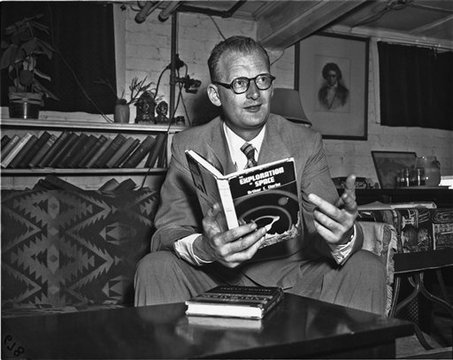

The future often happens sooner than seems possible but not as soon as we might hope, and I think nano-engineering fits into that category. I wouldn’t expect to see “living” architecture that morphs and modifies in my lifetime, not in any profound way, but there’s nothing theoretically impossible to prevent it happening at some indeterminate point. In 1956, Arthur C. Clarke, working from the theories of Richard Feynman, imagined a future full of buildings built and endlessly rebuilt by molecular engineering. From Darran Anderson’s excellent essay on the topic at Aeon:

Let’s elaborate Arthur C Clarke’s prophecy a little. Nanobots would create a programmable architecture that would change shape, function and style at command, in anticipation or even independently. Imagine an apartment where furniture fluidly morphs from the walls and floor, adapting to the inhabitants, an apartment that physically mutates into a Sukiya-zukuri tea-room or an Ottoman pleasure palace or something as yet unseen, while outside the entire skyline is continually rearranging itself. Architecture might become an art available to all.

The advantages of nanomaterials are already becoming apparent; consider the strength of graphene, the insulation of aerogel. The idea of a self-repairing, pollutant-neutralising, climate-adapting ‘living’ architecture no longer seems the preserve of fiction. Resistance to the idea of buildings that could grow (as in John Johansen’s forms) or liquefy (like William Katavolos’s designs) is almost as much a question of our conservatism as of technical limitations. But as the materials scientist Rachel Armstrong has observed, this vision of the city as a biological or ecological manifestation is not so much a leap into the unknown as a maturation of ancient Vitruvian ideals.

Every advance will have repercussions. The idea of walking through walls that simultaneously scan us for illnesses might sound promising – but what else will they monitor? Who will they answer to? What will it mean for human creativity, let alone employment, when there are buildings that can build themselves?•