In an excellent Five Books interview, writer Calum Chace suggests a quintet of titles on the topic of Artificial Intelligence, four of which I’ve read. In recommending The Singularity Is Near, he defends the author Ray Kurzweil against charges of techno-quackery, though the futurist’s predictions have grown more desperate and fantastic as he’s aged. It’s not that what he predicts can’t ever be be done, but his timelines seem to me way too aggressive.

Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence, another choice, is a very academic work, though an important one. Interesting that Bostrom thinks advanced AI is a greater existential threat to humans than even climate change. (I hope I’ve understood the philosopher correctly in that interpretation.) The next book is Martin Ford’s Rise of the Robots, which I enjoyed, but I prefer Chace’s fourth choice, Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson’s The Second Machine Age, which covers the same terrain of technological unemployment with, I think, greater rigor and insight. The final suggestion is one I haven’t read, Greg Egan’s sci-fi novel Permutation City, which concerns intelligence uploading and wealth inequality.

An excerpt about Kurzweil:

Question:

Let’s talk more about some of these themes as we go through the books you’ve chosen. The first one on your list is The Singularity is Near, by Ray Kurzweil. He thinks things are moving along pretty quickly, and that a superintelligence might be here soon.

Calum Chace:

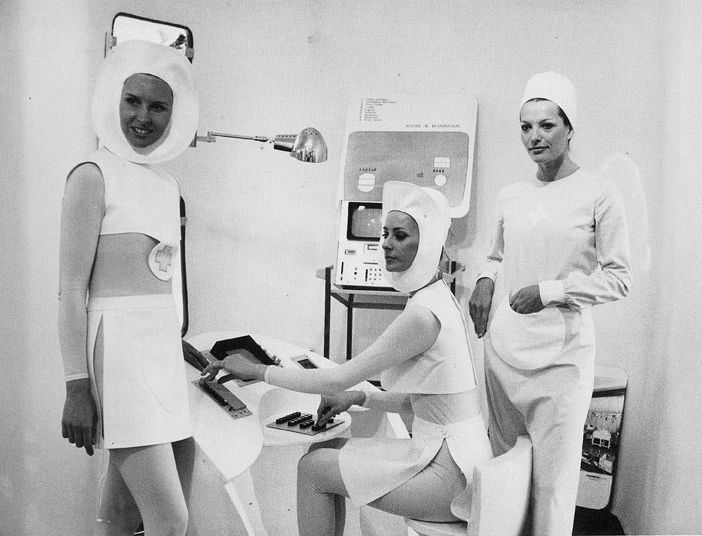

He does. He’s fantastically optimistic. He thinks that in 2029 we will have AGI. And he’s thought that for a long time, he’s been saying it for years. He then thinks we’ll have an intelligence explosion and achieve uploading by 2045. I’ve never been entirely clear what he thinks will happen in the 16 years in between. He probably does have quite detailed ideas, but I don’t think he’s put them to paper. Kurzweil is important because he, more than anybody else, has made people think about these things. He has amazing ideas in his books—like many of the ideas in everybody’s books they’re not completely original to him—but he has been clearly and loudly propounding the idea that we will have AGI soon and that it will create something like utopia. I came across him in 1999 when I read his book, Are We Spiritual Machines? The book I’m suggesting here is The Singularity is Near, published in 2005. The reason why I point people to it is that it’s very rigorous. A lot of people think Kurzweil is a snake-oil salesman or somebody selling a religious dream. I don’t agree. I don’t agree with everything he says and he is very controversial. But his book is very rigorous in setting out a lot of the objections to his ideas and then tackling them. He’s brave, in a way, in tackling everything head-on, he has answers for everything.

Question:

Can you tell me a bit more about what ‘the singularity’ is and why it’s near?

Calum Chace:

The singularity is borrowed from the world of physics and math where it means an event at which the normal rules break down. The classic example is a black hole. There’s a bit of radiation leakage but basically, if you cross it, you can’t get back out and the laws of physics break down. Applied to human affairs, the singularity is the idea that we will achieve some technological breakthrough. The usual one is AGI. The machine becomes as smart as humans and continues to improve and quickly becomes hundreds, thousands, millions of times smarter than the smartest human. That’s the intelligence explosion. When you have an entity of that level of genius around, things that were previously impossible become possible. We get to an event horizon beyond which the normal rules no longer apply.

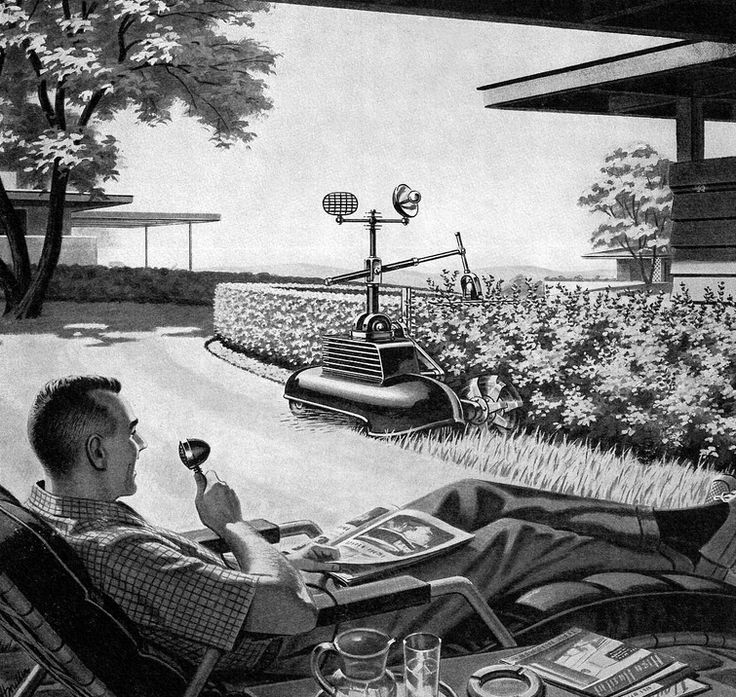

I’ve also started using it to refer to a prior event, which is the ‘economic singularity.’ There’s been a lot of talk, in the last few months, about the possibility of technological unemployment. Again, it’s something we don’t know for sure will happen, and we certainly don’t know when. But it may be that AIs—and to some extent their peripherals, robots—will become better at doing any job than a human. Better, and cheaper. When that happens, many or perhaps most of us can no longer work, through no fault of our own. We will need a new type of economy. It’s really very early days in terms of working out what that means and how to get there. That’s another event that’s like a singularity — in that it’s really hard to see how things will operate at the other side.•