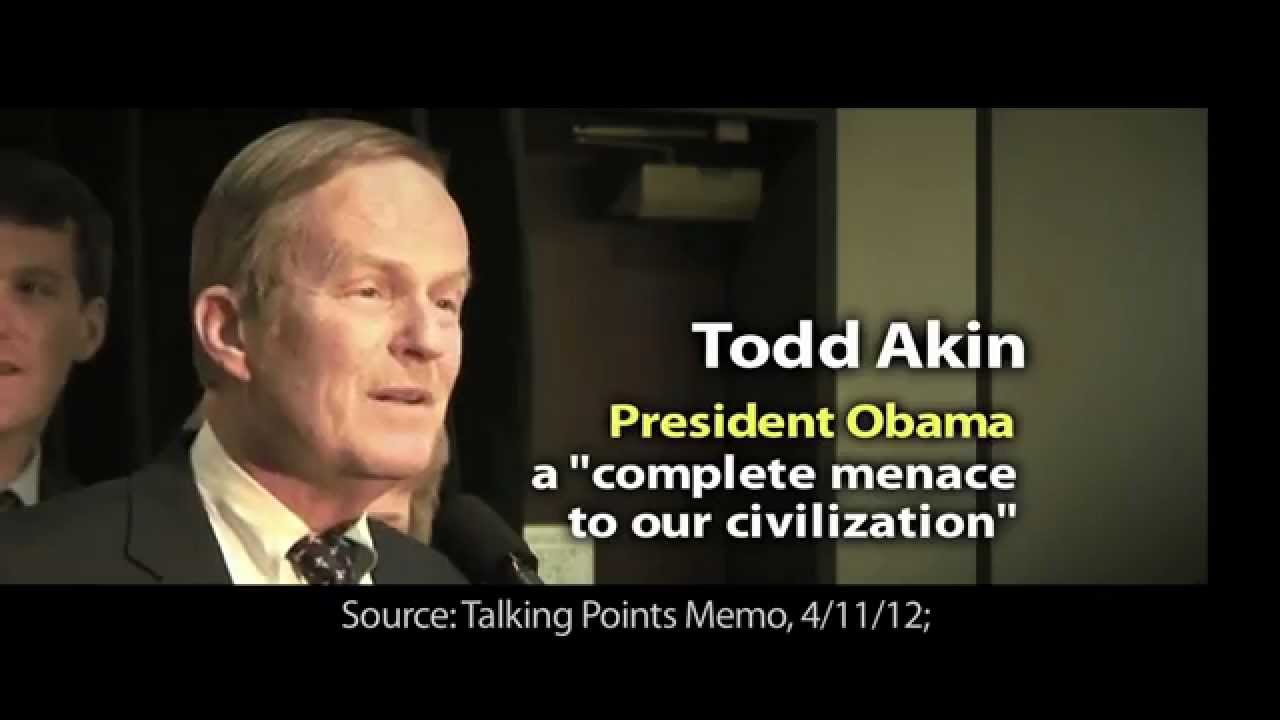

Was anybody else put off by Maureen Dowd’s New York Times op-ed about Donald Trump, in which she allowed the hideous hotelier to run roughshod over her column space, while labeling him as a “braggart” or “cartoonish,” when a more accurate description would have been “vicious racist”? Does it seem that an attempt at a fun piece about a gutter-level racist is wrong?

Not only is he king of the Birthers, but the hideous hotelier has also said that “laziness is a trait in blacks” and described Mexicans as “rapists.” That’s not someone who should be treated as an amusingly undiplomatic blowhard who sticks his foot into it by boasting about his golf courses or denying Heidi Klum perfect-ten status.

Dowd treated the whole sordid affair as if it was just harmless entertainment, an amusing sideshow (even featuring an extra-fun lightning round!), when Trump’s bigotry and those attracted to it are anything but a laugh. It’s unadulterated ugliness that should be called out by anyone who interviews him. Believing that the campaign is foolishness that will eventually blow away isn’t an excuse for a reporter to abdicate responsibility. In this instance, Dowd failed to be the equal of Megyn Kelly.

From her NYT piece:

The billionaire braggart known for saying unfiltered things is trying to be diplomatic. Sort of.

It has suddenly hit Trump that he’s leading the Republican field in a race where many candidates, including the two joyless presumptive nominees, are sputtering. He’s got the party by the tail — still a punch line but not a joke.

The Wall Street Journal huffed that Trump’s appeal was “attitude, not substance,” and the nascent candidate is still figuring out the pesky little details, like staff and issues, dreaming up his own astringent campaign ads for Instagram on ISIS and China.

The other candidates, he says, “have pollsters; they pay these guys $200,000 a month to tell them, ‘Don’t say this, don’t say that, you use the wrong word, you shouldn’t put a comma here.’ I don’t want any of that. I have a nice staff, but no one tells me what to say. I go by my heart. The combination of heart and brain. When Hillary gets up there she reads and then goes away for three days.”

As he headed off this weekend to see the butter cow in Iowa — “Iowa is very clean. It’s not like a lot of places where you and I would go, like New York City” — Trump is puzzling over a conundrum: How does he curb the merciless heckler side of himself, the side that has won over voters who think he’s a refreshing truth teller, so that he can seem refined enough to win over voters who think he’s crude and cartoonish?

How does he tone it down when he’s proud of his outrageous persona, his fiery wee-hours Twitter arrows and campaign “gusto,” and gratified by the way he can survive dissing John McCain and rating Heidi Klum when that would be a death knell for someone like Scott Walker?

“Sometimes I do go a little bit far,” he allowed, adding, after a moment: “Heidi Klum. Sadly, she’s no longer a 10.”•