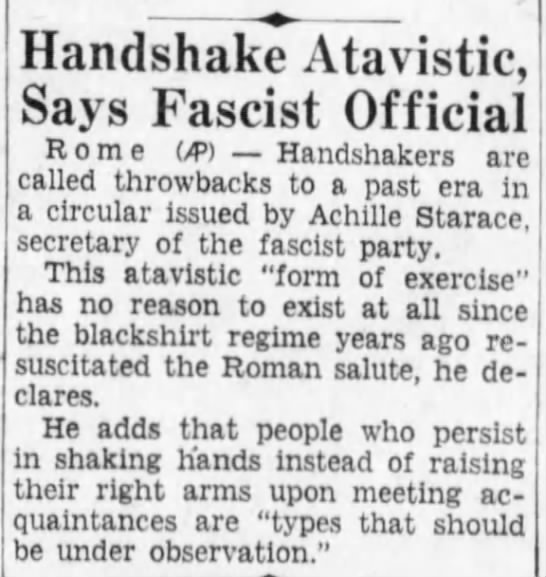

From the December 30, 1934 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Tags: Achille Starace

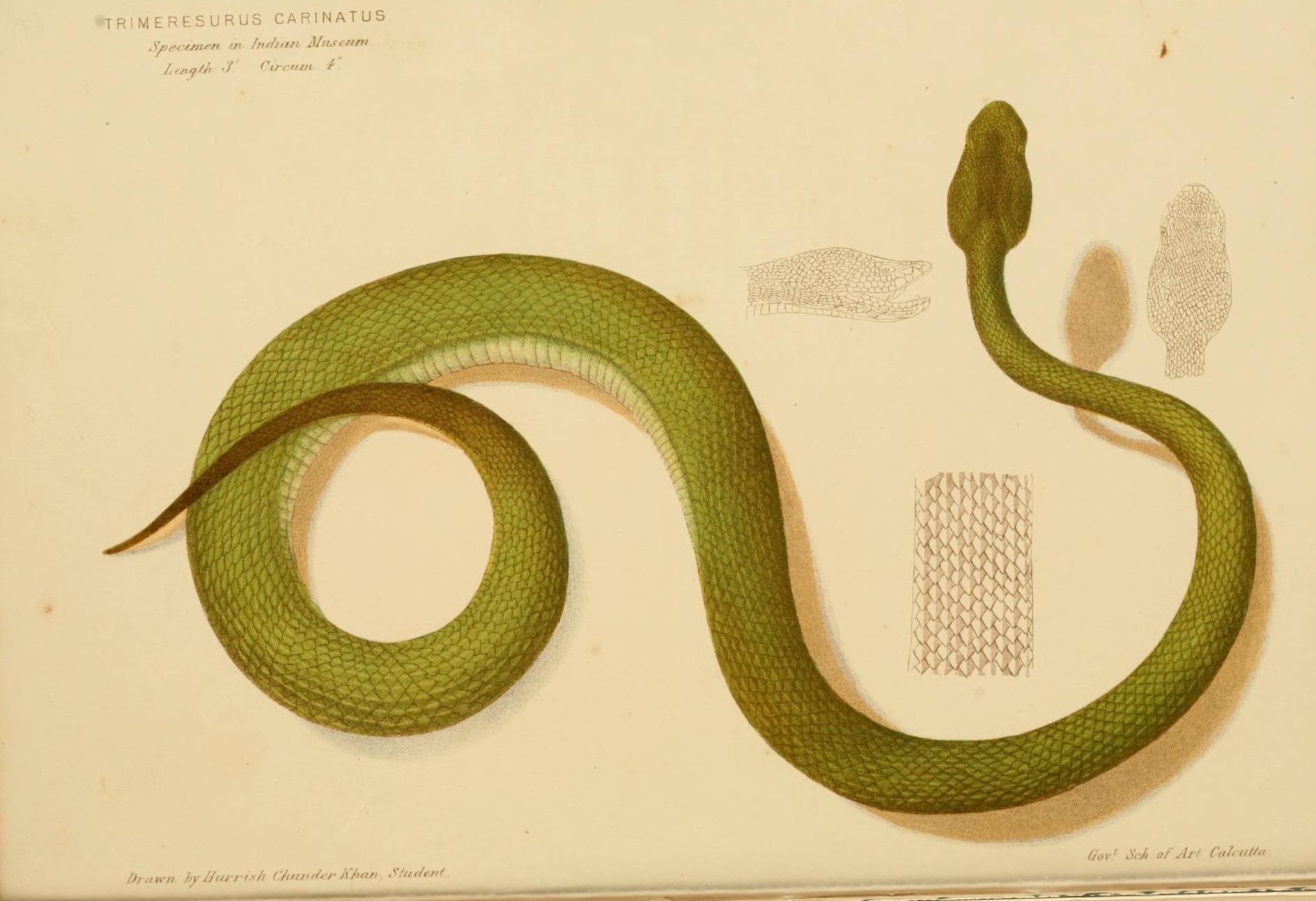

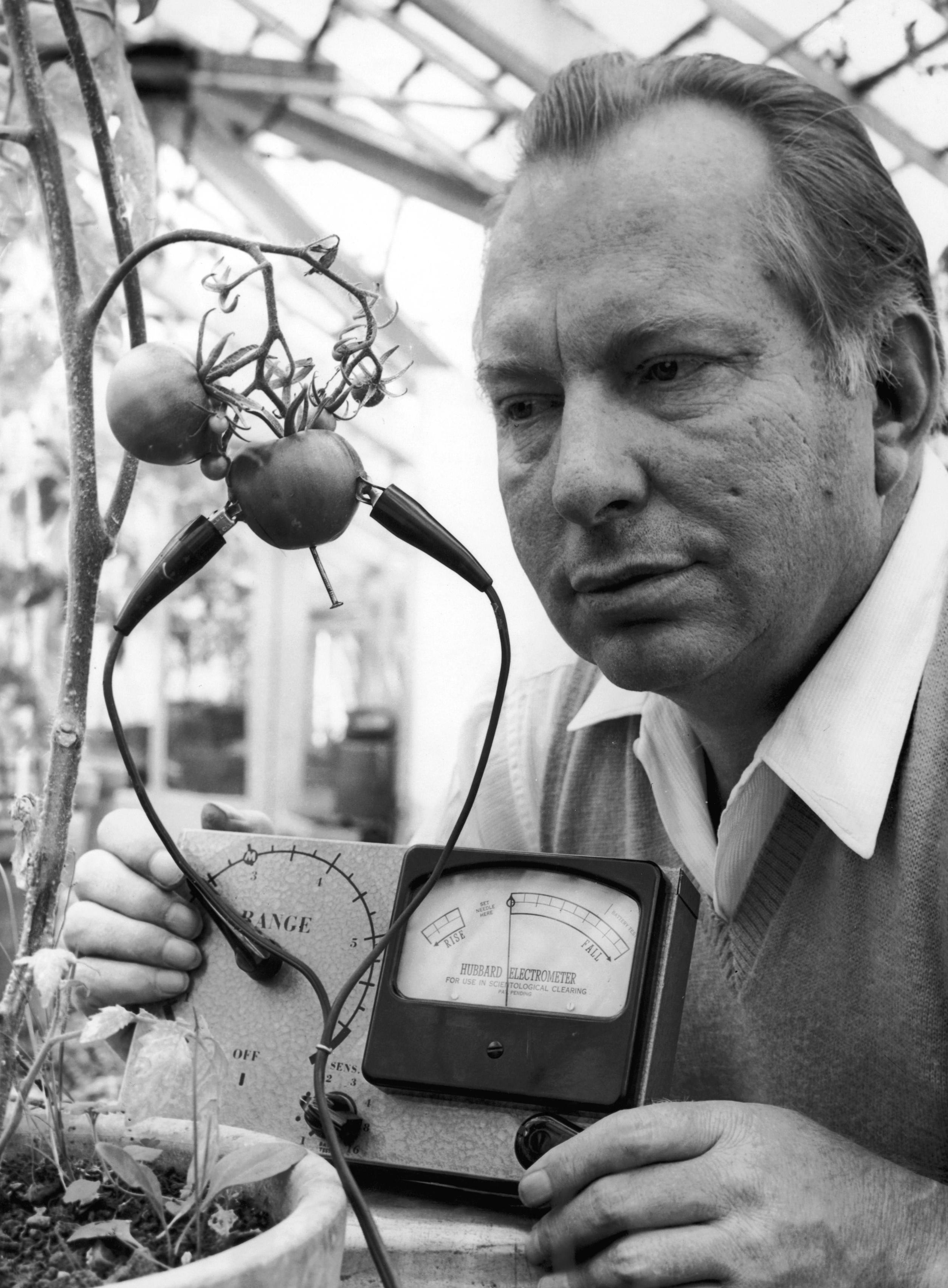

As we develop “perfect knowledge” of whole-planet genetics, the ability to manipulate DNA, to “edit’ life, to engineer evolution, will grow exponentially. Obviously, the consequences, intended and unintended, will be profound.

In Dawn Field’s new Aeon piece, one of my favorite essays of the year, the author wonders about a landscape of nights brightened by glowing trees, pigs nurtured to possess human organs for transplantation and a potential consolidated genetic registry. Diseases may be wiped out but so likely will any remnant of privacy. The idea of “bespoke creatures” may be discomfiting, but the author believes we should probably be more worried about the species we’re eliminating with climate change and other irresponsible behaviors. Lots of small, interesting facts (“Kuwait recently introduced mandatory DNA testing of its entire population as an anti-terrorism measure”) support an acute big-picture understanding.

An excerpt:

By 2020, many hospitals will have genomic medicine departments, designing medical therapies based on your personal genetic constitution. Gene sequencers – machines that can take a blood sample and reel off your entire genetic blueprint – will shrink below the size of USB drives. Supermarkets will have shelves of home DNA tests, perhaps nestled between the cosmetics and medicines, for everything from whether your baby will be good at sports to the breed of cat you just adopted, to whether your kitchen counter harbours enough ‘good bacteria’. We will all know someone who has had their genome probed for medical reasons, perhaps even ourselves. Personal DNA stories – including the quality of the bugs in your gut– will be the stuff of cocktail party chitchat.

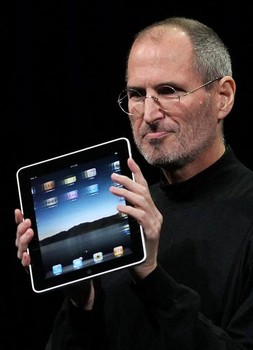

By 2025, projections suggest that we will have sequenced the genomes of billions of individuals. This is largely down to the explosive growth in the field of cancer genomics. Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, became one of the early adopters of genomic medicine when he had the cancer that killed him sequenced. Many others will follow. And we will become more and more willing to act on what our genes tell us. Just as the actress Angelina Jolie chose to undergo a double mastectomy to stem her chances of developing breast cancer, society will think nothing of making decisions based on a wide range of genes and gene combinations. Already a study has quantified the ‘Angelina Jolie effect’. Following her public announcement, the number of women turning to DNA testing to assess their risk for familial breast cancer doubled.

For better or worse, we will increasingly define ourselves by our DNA.•

Tags: Dawn Field

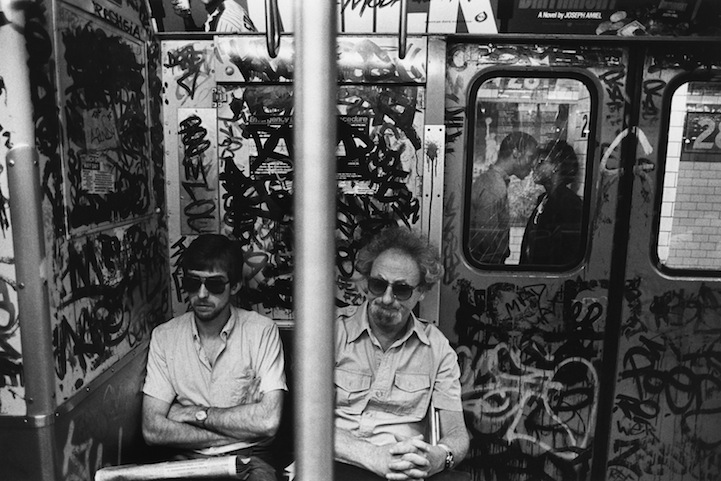

New York City has always been about money, but it wasn’t always only about money.

In a wonderfully written T Magazine piece, Edmund White wonders why there’s nostalgia for NYC of the 1970s and early 1980s, and I think I know the answer: Despite being something of a dangerous dump in those days, when even the President told us we could drop dead, that’s the last time the city belonged to us all, people of every class, before it became wholly about real estate and Wall Street. It was livable, you could make a living, even if sometimes you had to run for your life.

It wasn’t all good. For all the NYPD harassment of minorities now, the city then was much more divided racially. And the child prostitution that was allowed to flourish in Times Square isn’t something anyone could feel nostalgic about. But it did seem, on some level, we were all in it together. Most working-class people have now been pushed to the margins of the city by real-estate prices and gentrification and globalization, and that won’t stop until they go over the edge. That’s the only edge left.

White’s opening:

THERE IS A STRONG CURRENT of nostalgia for the late ’70s and early ’80s in New York, even among those who never lived through it — the era when the city was edgy and dangerous, when women carried Mace in their purses, when even men asked the taxi driver to wait until they’d crossed the 15 feet to the front door of their building, when a blackout plunged whole neighborhoods into frantic looting, when subway cars were covered with graffiti, when Balanchine was at the height of his powers and the New York State Theater was New York’s intellectual salon, when John Lennon was murdered by a Salinger-reading born-again, when Philip Roth was already famous, Don DeLillo had yet to become famous, and most literary insiders were betting on Harold Brodkey’s long-awaited novel, which his editor, Gordon Lish, declared would be ‘‘the one necessary American narrative work of this century.’’ (It flopped when it finally came out in 1991 as ‘‘The Runaway Soul.’’)

This was the last period in American culture when the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow still pertained, when writers and painters and theater people still wanted to be (or were willing to be) ‘‘martyrs to art.’’ This was the last moment when a novelist or poet might withdraw a book that had already been accepted for publication and continue to fiddle with it for the next two or three years. This was the last time when a New York poet was reluctant to introduce to his arty friends someone who was a Hollywood film director, for fear the movies would be considered too low-status.•

Tags: Edmund White

“Robots will show up in China just in time,” Daniel Kahneman has reportedly said, and that’s probably a true statement, though not an uncomplicated one. In order to sustain itself with a giant population that will go gray without also developing widespread automation, China will need robotics on a mass scale. Of course, the problem is huge swaths of the employed will be disappeared from their jobs. They will be promised a better life, better positions, but these guarantees won’t likely be true. It will be a transitional phase with great pain.

Other nations that will have to keep pace with China in this new “arms race,” even if they don’t have the same complex population issues. These countries, America included, will have to seek political solutions.

From Yue Wang at the South China Morning Post:

There is an automation revolution in China. Factory owners are turning to robots amid rising labour costs, worker-protests and greater demand for quality. In 2013, the country overtook Japan as the world’s largest market for industrial robots, accounting for 20 per cent of global supply, according to the International Federation of Robotics, an industry group based in Germany.

As robots march into Chinese factories, global automation companies are racing to invest. Demand is primarily driven by the car sector, which accounts for 40 to 50 per cent of robot demand in China, according to consultancy Solidiance.

But the big race is now in the electronics sector. Adapting robots to the needs of fast-changing production lines is a challenge for global players such as Japan’s Fanuc Corp, Yaskawa Electric Corp, German’s Kuka Corp and Swiss robot maker ABB.

“Robotics has the limitation of requiring intensive change-out to adapt to a new product model or production line scenario,” says Pilar Dieter, a partner at Solidiance. “If a robotics manufacturer can solve this dilemma, they will certainly hold a coveted position in the market.”•

Tags: Pilar Dieter, Yue Wang

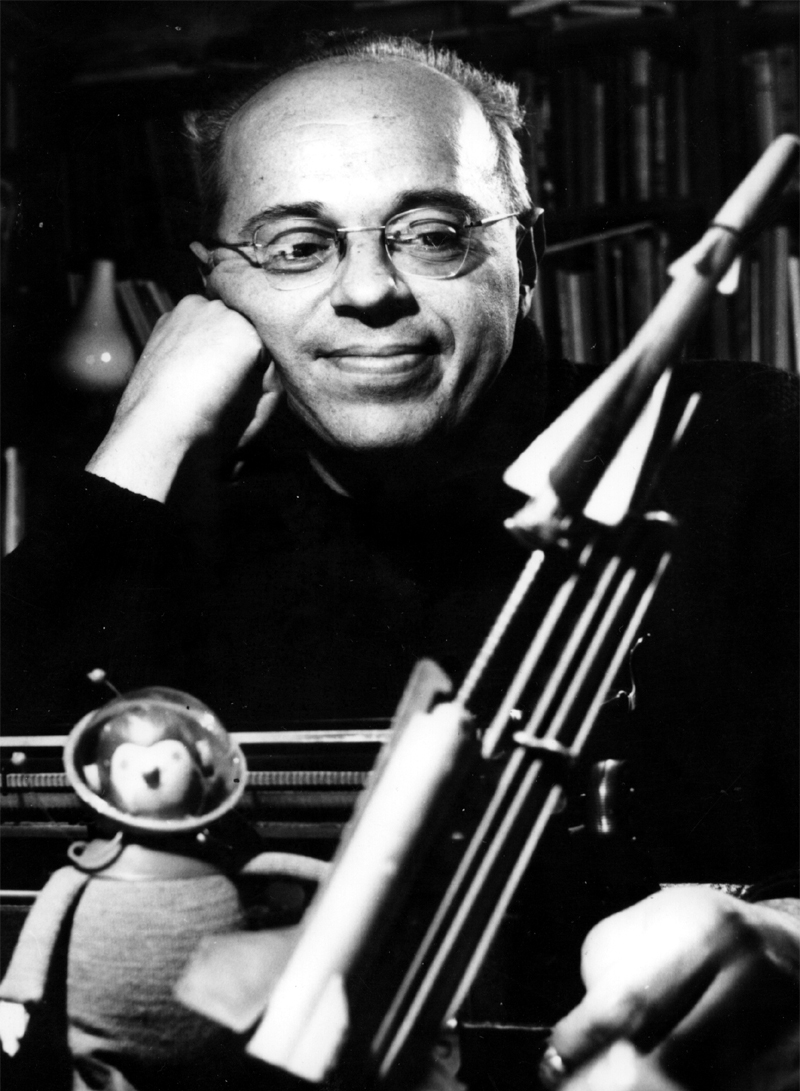

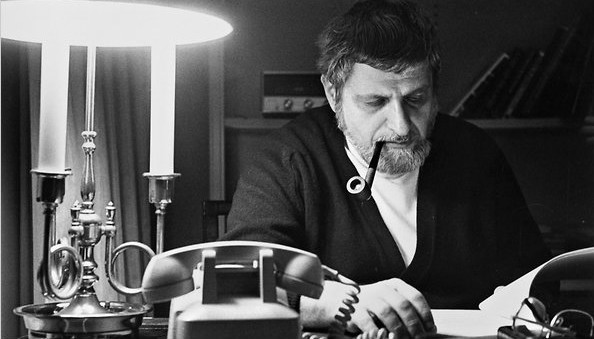

My problem with the late Polish author Stanislaw Lem stems from his disdain for Franz Kafka, an early influence whom he ultimately deemed “repugnant“–and he meant it in a negative way!

Lem, of course, was brilliant, a Hoover of knowledge with a jet pack inside his head, his attentions rapidly moving far and wide. His 1964 nonfiction work, Summa Technologiae, which wasn’t wholly translated into English until 2013, serves as the foundation for Lee Billings’ latest wonderful essay, the Nautilus piece “The Book No One Read.” (I’ll acknowledge I’m one of those impoverished souls.) Billings argues that Lem is something of a Digital Age Cassandra, warning us that past a point we’ll no longer be able to manage our technological progress if we don’t engineer what might be termed a posthuman superintelligence. In a sense, we will be the end of us, and that’s the most hopeful outcome. As Billings states, Lem was asking a very fundamental question: “Does technology control humanity, or does humanity control technology?”

An excerpt:

In its early stages, Lem writes, the development of technology is a self-reinforcing process that promotes homeostasis, the ability to maintain stability in the face of continual change and increasing disorder. That is, incremental advances in technology tend to progressively increase a society’s resilience against disruptive environmental forces such as pandemics, famines, earthquakes, and asteroid strikes. More advances lead to more protection, which promotes more advances still.

And yet, Lem argues, that same technology-driven positive feedback loop is also an Achilles heel for planetary civilizations, at least for ours here on Earth. As advances in science and technology accrue and the pace of discovery continues its acceleration, our society will approach an “information barrier” beyond which our brains—organs blindly, stochastically shaped by evolution for vastly different purposes—can no longer efficiently interpret and act on the deluge of information.

Past this point, our civilization should reach the end of what has been a period of exponential growth in science and technology. Homeostasis will break down, and without some major intervention, we will collapse into a “developmental crisis” from which we may never fully recover. Attempts to simply muddle through, Lem writes, would only lead to a vicious circle of boom-and-bust economic bubbles as society meanders blindly down a random, path-dependent route of scientific discovery and technological development. “Victories, that is, suddenly appearing domains of some new wonderful activity,” he writes, “will engulf us in their sheer size, thus preventing us from noticing some other opportunities—which may turn out to be even more valuable in the long run.”•

Tags: Lee Billings, Stanislaw Lem

When it’s time to make a decision, the choice isn’t best left to instinct. It’s clearly better to have some idea, to study and do research, but where’s the line between a tool that helps you do so and a decision engine?

If machines can eventually fly and drive and reason better than us, will that free us up to redefine our role or leave us with none? I think in the very long term, we’ll be the “machines” that replace us, but if I’m wrong, we could exit stage left.

From Keiko Nannichi’s Asahi Shimbun piece about Hitachi’s new “decision software”:

During a recent demonstration, a prototype was asked whether the ban on casinos should be lifted in Japan.

In favor of the ban, the program said more people would become addicted to casino gambling, and that it is likely to spur the incidence of crime.

It cited job creation and impact on stimulating the economy as grounds for lifting the ban.

The program came up with for and against reasons after it scanned as many as 9.7 million English-language news articles in about 60 seconds.

The program first establishes the theme of the question asked and then gathers related articles. It then locates passages describing reasons and grounds for and against the casino industry and compiles and reads texts on both positions.

The program can be applied to many fields as more data become available in various fields, according to Hitachi.

For example, the AI program could perform a similar task in assisting doctors on deciding whether to proceed with surgery if electronic data on patients and relevant research literature are presented.•

Tags: Keiko Nannichi

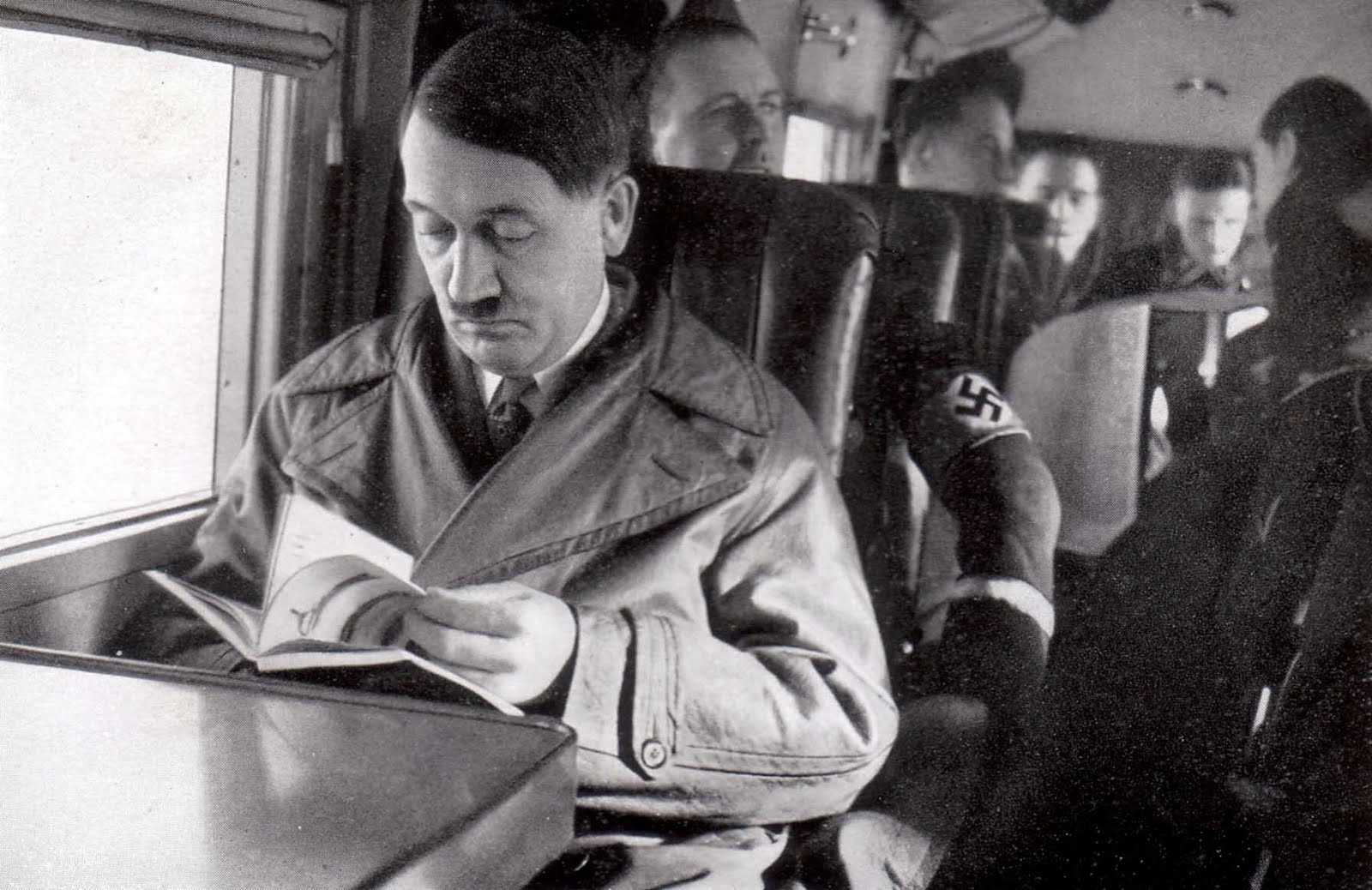

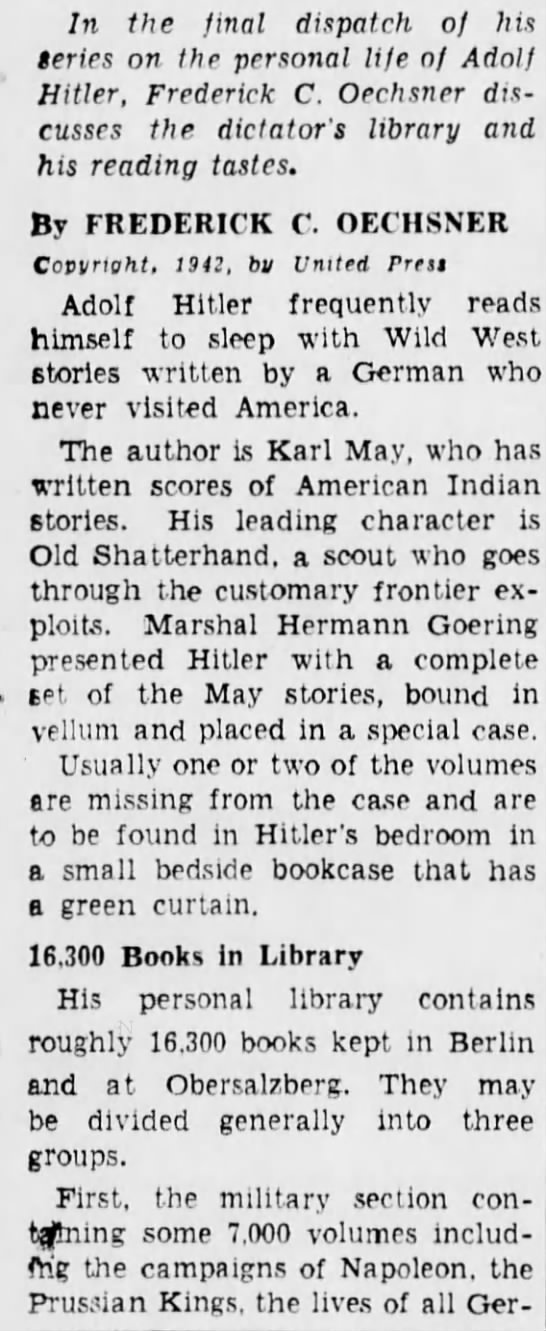

Making complete sense of the perfect storm of hatred and insanity that enabled Nazi Germany is impossible, but still we try. Are there any clues in the elaborate personal library that madman Adolf Hitler assembled? Probably not, but for curiosity’s sake, he was particularly enamored with the work of Karl May, a writer of Westerns who never visited America. (In all fairness to May, Albert Einstein was also a fan.) During the heat of WWII, an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle looked at the titles on Hitler’s shelves, trying to make some sense of it all.

Tags: Adolf Hitler, Karl May

Education now is largely preparation for a world that won’t exist on graduation day, and it’s not entirely the fault of our learning system. No one can really pinpoint where to from here, not with robotics and AI moving forward in a rapid but unpredictable manner. It’s difficult to learn to dance on a moving floor. Professions can rise and fall in a day, relatively speaking.

In a Fast Company piece, Ryan Holmes offers prescriptions which aren’t new but are the best we currently have: a more free-range education based on the Montessori method and guaranteed basic income. An excerpt:

White-collar roles once thought to be the exclusive domain of human beings could also end up on the chopping block. The first to go, according to the experts Pew surveyed, include paralegals, bookkeepers, transcriptionists, and medical secretaries. The widespread use of DIY tax and finance software and automatic transcription tools like Siri only hints at the changes to come in these sectors. The important thing to note is that these jobs aren’t just repetitive mechanical functions. They require an ability to learn and adapt to new information. And this is precisely why the coming AI revolution is so scary.

I’ve seen how quickly new roles can appear and disappear even in my own sector, social media. Just a few years ago, “social media manager” was one of the most in-demand job functions on the career site Indeed.com. Then social media management tools—including those made by my company, Hootsuite—became more widespread and easy to use. Social media use has increased exponentially since then, but demand for dedicated social media managers hasn’t kept pace. This is still a critical role in large organizations, but for many businesses, ever more sophisticated technology has transformed social media from a discrete job into something that people all across an organization can do. …

Promoting creativity and encouraging independent thinking might help us stay ahead of job losses in the short term. But in the long term, advanced robots may well be able to execute even some of these uniquely “human” functions better than we can. Here we’re getting into the realm of “strong” or “full” AI—machines that aren’t just able to learn basic tasks but can master pretty much anything. If you’re a futurist, this is when talk of the “singularity” comes into the picture—the moment when computers can make themselves smarter, leading to capabilities that match, and then quickly exceed, our own.•

Tags: Ryan Holmes

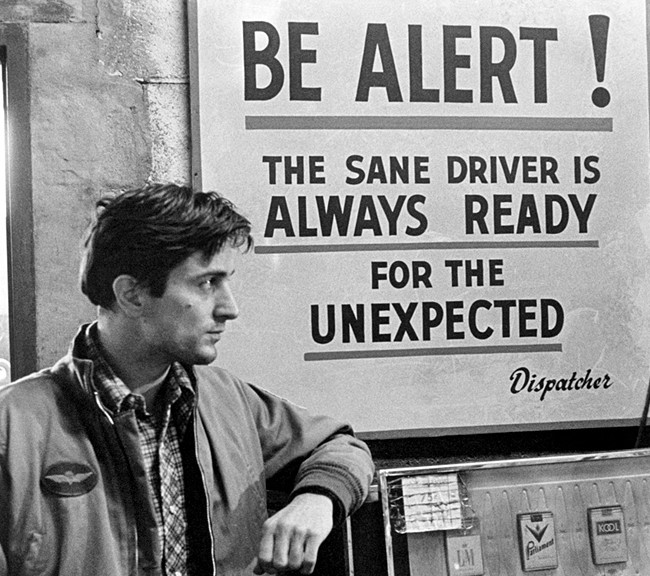

Reassessment–a chastening, even–often attends the publication of a biography, especially in the cases of writers or politicians. Joan Didion’s received a surprising number of calls for impeachment with the publication of Tracy Daugherty’s book about her.

I’ve never been a fan of Play It As It Lays (leave the smut to the professionals, please), but Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album are sensational (in the best sense of the word). Yes, Didion was a fashion-magazine veteran savvy enough to wear cool sunglasses and pose at the wheel of her Stingray, but her efforts at auto-iconography don’t even rate when compared to, say, Hunter S. Thompson’s. Since they both had the chops, who even cares?

A lot of the backlash stems from the then-aphasiac author’s depiction of California as haywire during the ’60s and ’70s. Her home state, that traitor! Sure, a big-picture take of the fantasia that is California can’t completely satisfy, and perhaps her portrait flattered East Coasters, but maybe most disturbing is that she did land on numerous and troubling truths of that place in that time. Although some will argue that these were mere distortions.

From a very well-written Barnes & Noble review of Daugherty’s bio by Tom Carson, a self-described Didion skeptic:

In her prime, she didn’t have casual readers; her gift for imposing her sensibility on events didn’t permit it. The paradox of The Year of Magical Thinking‘s success was that it introduced her to a nonliterary audience largely unaware that she’d been generating intimations of morbidity, desolation, and the existential jitters out of pretty much any topic put in front of her, from 1968’s career-defining essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem on. When “California” still blended the worst of heaven and the best of hell in Noo Yawk intellectuals’ minds, no other writer matched native daughter Didion at being the anti−Beach Boys.

In her home state’s very entertaining transformation from freakish American exotica to the place lit by rockets’ pink glare that the other forty-nine all try to be, she’s a pivotal figure: the last West Coast chronicler to make a career of insisting that where she came from was special, strange, and always latently monstrous. That happened to be precisely the view her culturally unnerved audience wanted endorsed at the time, but Didion also invited derision by treating her perpetually threatened morale as the ultimate gauge of how badly the twentieth century was botching its job. In a memorable hit piece, Barbara Grizzuti Harrison called her “a neurasthenic Cher.” Pauline Kael read Didion’s “ridiculously swank” 1970 novel Play It as It Lays “between bouts of disbelieving giggles.” Maybe not insignificantly, she tends to drive other woman writers up the wall — especially if, like Kael, they’re California gals themselves — more than men, who usually flip for her solemn tension.•

__________________________________

In the 1970s, Tom Brokaw profiled Didion, when she still called California home.

Tags: Joan Didion, Tom Carson, Tracy Daugherty

More than any other reason, Donald Trump has supporters–a loud minority, no matter what he says–because some Americans feel awful and want to stamp their feet and say they’re great. That’s what people do when they’re at their worst, their most bitter. Easier to do that than seek real solutions.

Michael Moore is releasing a new documentary about American militarism, the brilliantly titled Where to Invade Next, and sat for a Q&A with the Vice staff. (They’ve labeled it an “exclusive” because Moore is famously shy and probably won’t do any more press for the film.) I interviewed Moore years ago and he’s a nice, bright guy, though I don’t agree with his political purity. That’s what led him to support Ralph Nader in 2000, in the ludicrous belief that there was no difference Bush and Gore. It’s what drove Moore to lambaste the Affordable Care Act, a flawed piece of legislation I’ll agree, but a marked improvement and a huge step in the right direction. Whether it’s some demanding exceptionalism or others accepting only perfection, it’s puzzling when adults see the world in only black and white.

An excerpt from Vice:

Question:

But don’t you also think that the country has to be open to introspection? The narrative of American exceptionalism—the idea that this is the best, bravest, most free country ever—to me suggests a culture that is not introspective. Do you think Americans are introspective?

Michael Moore:

Well, I think that American exceptionalism will be the death of us. It’s almost like saying we don’t really need to find a cure for cancer ’cause we’re big enough and brave enough to suck it up and get through it. It’s the sort of belief that we’re on top when we’re not.

Question:

What do you think politicians are trying to say when they talk about American exceptionalism?

Michael Moore:

They’re trying to make people feel good, who deep down inside don’t feel good… In America we keep saying, “We’re number one, we’re number one,” and it’s at the point now where we need to think about who we are really trying to convince.

The facts don’t bear it out. We’re not number one in education, we’re not number one in mass transit, we’re not number one in health care, we’re not number one in… name it, you know?

Question:

So is your film documenting the death of the American dream?

Michael Moore:

I think you could say that about my earlier films, but I think that that so-called dream is already dead. And people know it. But they also really realize that it’s also just what it says it was: a dream. It wasn’t the American reality. It was a dream. And the dream has become a nightmare for millions of people because they’re not going to get the life that their parents had, and they know their kids are not going to get to have the life that they’ve had.•

Tags: Michael Moore

Can Homo sapiens survive climate change, the long recovery process that will follow it and become a thriving multi-planet species? Not without huge changes.

In an excellent Nautilus interview astrobiologist David Grinspoon conducted with writer Kim Stanley Robinson, the sci-fi author discusses how humans can endure the Anthropocene. Robinson believes it will require a global economic system with ecology at its heart. Hard to imagine that shift, even with a planetary Easter Island in our eyes. Perhaps when it’s even clearer that there’s no other choice we’ll make the right one?

One exchange:

David Grinspoon:

So, are we talking evolution or revolution? Do we need to escape from path dependence and start anew?

Kim Stanley Robinson:

No, we have to alter the system we already have, because like an animal with evolutionary constraints, we can’t change everything and start from scratch. But what we could do is reconstruct regulations on the existing global economic system. For this, we would need to wrench capitalism so that the global rules of the World Bank, etc., required ecological sustainability as their main criterion. That way, prices would shift to match their true costs. Burning carbon would cost more than it does now, and clean energy would become cheaper than burning carbon. This would address the most pressing part of our crisis, but finding a replacement for the market to allocate goods and price them is not easy.

As we enter this new mass extinction event, at some point there is going to be a global civilization response that will try to deal with it: try to cope, survive, and repair landscapes and ecosystems. The scientific method and democratic politics are going to be the crucial tools, I’d say. For them to work, we need universal justice and education because we need active and well-educated citizens who are empowered and live at adequacy.

From where we are now, this looks pretty hard, but I think that’s because capitalism as we know it is represented as natural, entrenched, and immutable. None of that is true. It’s a political order and political orders change. What we want is to remember that our system is constructed for a purpose, and so in need of constant fixing and new tries.•

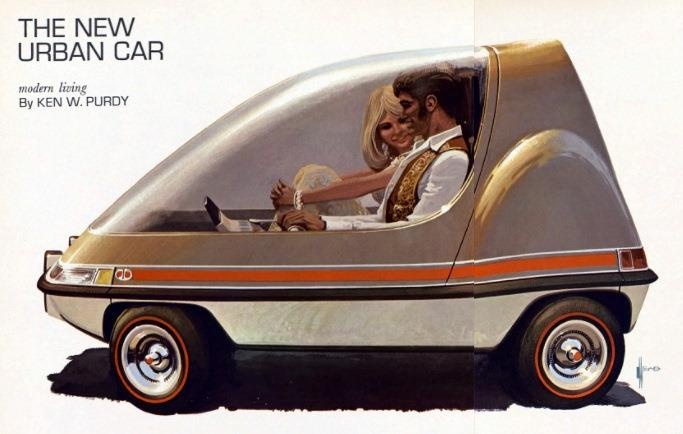

American auto sales have ticked up since the beginning of our unbalanced economic recovery, but teens are no longer rushing to get licenses and become owners, which sends a mixed message about the idea that we’re passed peak-car, an idea which began reverberating in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse.

The belief was that smartphones, not cars or motorcycles, were now the tools of freedom, and that’s true, but the changes also have to do with the flattening of the middle class, the skyrocketing of college-tuition costs and the emergence of the Gig Economy.

Certainly the sector is bracing for a radical reimagining, with driverless cars in development and more powerful companies hoping to enter the already robust rideshare sector. The auto industry might hope the shift away from purchases are more fashion than fundamental, but for that to be true two major trends–the rush toward urban living and the proliferation of mobile devices–would have to be reversed. And that’s not happening.

One caveat to all this is we may have passed peak-car only according to the rules imposed by Big Auto. 3-D printers might reawaken the want for wheels if costs fall precipitously and vehicles become green and highly customizable.

From Marc Fisher’s Washington Post article “Cruising Toward Oblivion“:

For nearly all of the first century of automobile travel, getting your license meant liberation from parental control, a passport to the open road. Today, only half of millennials bother to get their driver’s licenses by age 18. Car culture, the 20th-century engine of the American Dream, is an old guy’s game.

“The automobile just isn’t that important to people’s lives anymore,” says Mike Berger, a historian who studies the social effect of the car. “The automobile provided the means for teenagers to live their own lives. Social media blows any limits out of the water. You don’t need the car to go find friends.”

Much of the emotional meaning of the car, especially to young adults, has transferred to the smartphone, says Mark Lizewskie, executive director of the Antique Automobile Club of America Museum in Hershey, Pa. “Instead of Ford versus Chevy, it’s Apple versus Android, and instead of customizing their ride, they customize their phones with covers and apps,” he says. “You express yourself through your phone, whereas lately, cars have become more like appliances, with 100,000-mile warranties.”

The number of vehicles on American roads soared every year until the recession hit in 2008. Then the number plummeted. Recently, it’s crept back up. Similarly, the number of drivers has leveled off. …

No, it’s the economy, stupid, some car industry analysts and executives say. The recession hit this generation just as it was about to put down roots. Fewer jobs meant less money, which translated into an inability to buy, insure or maintain a car.

Now, as the economy bounces back, auto sales are up 4 percent in the first half of this year. Americans are choosing big vehicles again. Thanks in part to low gas prices, sales of SUVs and light trucks are up. Sedans, subcompacts, hybrids and electrics are down.

“This is all actually economics, not preferences,” says Sean McAlinden, chief economist at the Center for Automotive Research, a nonprofit group funded by government and industry grants. When the cost of owning a car drops below 10 percent of income, “young people will stop telling pollsters they can do without cars. You say you’re not interested in owning something if you can’t afford it,” he argues.•

Tags: Marc Fisher, Mike Berger, Sean McAlinden

The sluggishness of legislation to keep pace with drone development isn’t a surprise, but it’s still worrisome. Looking back to the Montgolfier brothers’ 18th-century experimentation with hot-air ballooning and forward to a time when the drone is ubiquitous,

Drones are set to become a defining feature of this century. Thousands are already in operation in most developed countries worldwide – and that is likely to grow to hundreds of thousands as drones of different shapes and sizes are deployed by the media, emergency services, scientists, farmers, sports enthusiasts, hobbyists, photographers, the armed forces and government agencies.

Eventually commercial uses will dwarf all others. Amazon promises to deliver purchases within 30 minutes via delivery drones. Domino’s Pizza has staged hot pizza drone delivery. More than 20 industries are approved to fly commercial drones in the US alone, and developing countries are following suit.

The question is, is this boom in drones moving faster than the law? How to fit such a proliferation of drones into the current regulations? The answers will need to be written into national and international laws quickly in order to govern an increasingly busy airspace. Many existing laws may need to be tweaked, including those governing cyber-security, stalking, privacy and human rights legislation, insurance, contract and commercial law, even the laws of war.•

I don’t agree with Elon Musk that there’ll be less physical movement in the future because of Virtual Reality, not if we’re measuring step for step and gesture for gesture. We will likely see fewer miles traveled, however. Business trips, for instance, will be radically changed by VR. Perhaps, as J.G. Ballard predicted nearly four decades ago, everyone is staying home.

From Kia Makarechi at Vanity Fair:

“It’s quite transformative,” Musk said. “You really feel like you’re there, and then when you come out of it, it feels like reality isn’t real.”

“I think we’ll see less physical movement in the future, as a result of the virtual-reality stuff,” Musk said.

As video games get more lifelike and incorporate technologies such as haptic suits, Musk noted, “it becomes, beyond a certain resolution, indistinguishable from reality.”

The entrepreneur and futurist then offered a twist: “There are likely to be millions, maybe billions of such simulations. So, then, what are the odds that we’re actually in base reality? Isn’t it one in billions?”•

Tags: Elon Musk, Kia Makarechi

In both the CBS News video I embedded yesterday and in the recent Nieman Reports article by Celeste LeCompte, an argument is made that the automation of newsrooms, a process that began back in the 1970s, is a good thing that’ll free up the hands of journalists to do more important work. Well, that’s part of the story.

Seasoned reporters who could do more than an inverted triangle piece always did so. This arrangement isn’t a new occurrence courtesy of the Second Machine Age. Those small-scale stories were mostly a training ground for cubs to practice a formula and grow beyond it. Software taking on this task will mean fewer hires and less-on-the-job learning, ultimately providing a smaller pool of potential talent and fewer eyes, ears and voices–at least on the professional end of things. And that, of course, doesn’t even begin to speak to the missteps, ethical and otherwise, that will occur.

I’m not saying such software isn’t a useful tool; it certainly is. But as is always the case with technology, something’s lost as something’s gained.

The Nieman Reports opening:

Philana Patterson, assistant business editor for the Associated Press, has been covering business since the mid-1990s. Before joining the AP, she worked as a business reporter for both local newspapers and Dow Jones Newswires and as a producer at Bloomberg. “I’ve written thousands of earnings stories, and I’ve edited even more,” she says. “I’m very familiar with earnings.” Patterson manages more than a dozen staffers on the business news desk, and her expertise landed her on an AP stylebook committee that sets the guidelines for AP’s earnings stories. So last year, when the AP needed someone to train its newest newsroom member on how to write an earnings story, Patterson was an obvious choice.

The trainee wasn’t a fresh-faced j-school graduate, responsible for covering a dozen companies a quarter, however. It was a piece of software called Wordsmith, and by the end of its first year on the job, it would write more stories than Patterson had in her entire career. Patterson’s job was to get it up to speed.

Patterson’s task is becoming increasingly common in newsrooms. Journalists at ProPublica, Forbes, The New York Times, Oregon Public Broadcasting, Yahoo, and others are using algorithms to help them tell stories about business and sports as well as education, inequality, public safety, and more. For most organizations, automating parts of reporting and publishing efforts is a way to both reduce reporters’ workloads and to take advantage of new data resources. In the process, automation is raising new questions about what it means to encode news judgment in algorithms, how to customize stories to target specific audiences without making ethical missteps, and how to communicate these new efforts to audiences.

Automation is also opening up new opportunities for journalists to do what they do best: tell stories that matter. With new tools for discovering and understanding massive amounts of information, journalists and publishers alike are finding new ways to identify and report important, very human tales embedded in big data.

The Economist interview with Donald Trump isn’t as woeful as the Maureen Dowd one for the New York Times, but it still isn’t very good. There are precious few follow-up questions to counter the subject’s usual nonsense about race, global politics and his biography and nothing at all about how consistently and drastically wrong this self-styled economic genius has been about money matters in recent years. It seems the publication was happy to have a Q&A with someone so prominently in the news and performed like a matador, stepping aside to let the bull rush on through. When someone’s made the type of odious racist and xenophobic statements Trump has, sounding deeply fascistic in the process, either do a thorough job or don’t do it at all.

Two exchanges follow.

_______________________

The Economist:

If the terms of trade can be changed, as you say, why haven’t today’s politicians of either party done it?

Donald Trump:

Because they’re grossly incompetent. And they are not negotiators. And they are grossly incompetent. And I have friends from China – by the way I love China. I love Japan. I have people that buy my apartments, I have people that work for me from China. I love Mexico. I mean, Mexico, I have thousands of people from Mexico that work for me. Thousands. Hispanics. In fact a poll just came out, Public Policy Polling, where I am leading with Hispanics, can you believe that, after what you have been hearing? I’m leading, I’m number one with Hispanics.

_______________________

The Economist:

You use the phrase “silent majority” that Nixon used in 1969. Do you hear echoes of that time now?

Donald Trump:

No, it doesn’t echo. I’ll tell you what. I’ve heard the term, but for the last 20 years I really haven’t heard the term. But I went to a rally in Alabama, and there were 31,000 people there, you’ve seen it, you’ve read about it. It was the largest, the most amount of people – a lot of people say in the history of primaries, because you know, I mean, you are talking about…certainly in the history of early primaries. Because 31,000 people. It was going to be in a hotel, 500 people, and then it turned out to be 10,000 people and then it turned… so we went from a hotel to a convention centre to a football stadium. So we had 31,000 people and it was amazing. And I looked and I said, this is the silent majority. Though they weren’t silent, because they want to see proper change, not Obama change. And what happened is, I thought of that term, I just said the words silent majority. Now, it hasn’t been used in a long time because I guess it is associated somewhat with Nixon. But honestly it’s two words, that when you put together describe what is happening very well. There’s a group of people, great people in this country that have been disenfranchised. Their country has been taken away from them. Things have happened, having to do with many things including political correctness, where people are so worried about being politically correct that they are unable to function. And with me, hey, look I’m politically correct, I went to a great school, I was a good student, look, I’m a smart guy. I built a great company. I did The Art of the Deal which is the number one selling business book of all time, I did many other best-sellers. You know, I did 12 best-sellers. I did The Apprentice, which was one of the most successful television shows of the last 25 years. You know, all that stuff. But the words “silent majority”, the words “silent majority” are very descriptive of what is happening with me.•

Tags: Donald Trump

You can find in President Trump’s support the desire for an illusory America that will never be. The very complex problems which the candidate is ill-prepared to address have been dutifully avoided. There’s no discussion of automation vanishing jobs. There’s no talk about how China is the world leader in cancer rates and air pollution as partial payment for its hellbent shift into capitalism. You’ll hear from Trump that Dubai has such beautiful, modern airports and lavish golf courses because that state’s leaders are much smarter than ours are, but there’s no mention of their willingness to use quasi-slave labor.

In a London Review of Books piece about the ongoing refugee crisis, Slavoj Žižek examines the need for a nouveau forms of slavery in the contemporary global economy. These people are still cheaper than machines, for now.

An excerpt:

New forms of slavery are the hallmark of these wealthy countries: millions of immigrant workers on the Arabian peninsula are deprived of elementary civil rights and freedoms; in Asia, millions of workers live in sweatshops organised like concentration camps. But there are examples closer to home. On 1 December 2013 a Chinese-owned clothing factory in Prato, near Florence, burned down, killing seven workers trapped in an improvised cardboard dormitory. ‘No one can say they are surprised at this,’ Roberto Pistonina, a local trade unionist, remarked, ‘because everyone has known for years that, in the area between Florence and Prato, hundreds if not thousands of people are living and working in conditions of near slavery.’ There are more than four thousand Chinese-owned businesses in Prato, and thousands of Chinese immigrants are believed to be living in the city illegally, working as many as 16 hours a day for a network of workshops and wholesalers.

The new slavery is not confined to the suburbs of Shanghai, or Dubai, or Qatar. It is in our midst; we just don’t see it, or pretend not to see it. Sweated labour is a structural necessity of today’s global capitalism. Many of the refugees entering Europe will become part of its growing precarious workforce, in many cases at the expense of local workers, who react to the threat by joining the latest wave of anti-immigrant populism.

In escaping their war-torn homelands, the refugees are possessed by a dream. Refugees arriving in southern Italy do not want to stay there: many of them are trying to get to Scandinavia. The thousands of migrants in Calais are not satisfied with France: they are ready to risk their lives to enter the UK. Tens of thousands of refugees in Balkan countries are desperate to get to Germany. They assert their dreams as their unconditional right, and demand from the European authorities not only proper food and medical care but also transportation to the destination of their choice. There is something enigmatically utopian in this demand: as if it were the duty of Europe to realise their dreams – dreams which, incidentally, are out of reach of most Europeans (surely a good number of Southern and Eastern Europeans would prefer to live in Norway too?). It is precisely when people find themselves in poverty, distress and danger – when we’d expect them to settle for a minimum of safety and wellbeing – that their utopianism becomes most intransigent. But the hard truth to be faced by the refugees is that ‘there is no Norway,’ even in Norway.•

Tags: Slavoj Žižek

Apple has managed Steve Jobs’ legacy so well that people no longer mention the company has failed to deliver the next killer product after the iPod, iPhone and iPad. Unless, of course, you count the Apple Watch, and if you do, you’re alone. The ridiculous sum earned from the middle of the Jobs 2.0 trio of inventions has overwhelmed all talk of the company losing its edge. For now, at least.

Tim Cook et. al. realize that won’t always be the case, so like the rich company it is, Apple is pouring money into major categories which seem poised to play a major role in commerce this century: transportation and AI. Those, of course, are also two sectors that are going to coalesce.

Excerpts follow from reports on Apple’s growing interest in autos and machine learning.

_________________________

From Chris Mims’ WSJ piece, “What to Expect When You’re Expecting an Apple Car“:

Technology is set to radically transform everything from who owns automobiles to how they work, and much of this change is driven by the very mobile devices that are Apple’s bread and butter. If Apple is serious about maintaining its gargantuan size, it needs to participate in this change, even if it’s just at the level of experimenting with how it can integrate its software and hardware into the transportation system of the future. Even if, as Apple has often said about its ventures into television, cars start out as just a “hobby.”

Take self-driving cars. There’s plenty of evidence, from hiring and patents to an open records request by U.K. newspaper the Guardian, that Apple is at least thinking about building them.

Estimates for when self-driving technology will be ready for widespread adoption range from the wildly optimistic—five years, according to the head of self-driving technology at Google Inc.—to decades after, perhaps even somewhere beyond 2040.

That’s an eternity in technology years.•

_________________________

From Julia Love’s Reuters piece about Apple collecting AI talent:

Apple has ramped up its hiring of artificial intelligence experts, recruiting from PhD programs, posting dozens of job listings and greatly increasing the size of its AI staff, a review of hiring sites suggests and numerous sources confirm.

The goal is to challenge Google in an area the Internet search giant has long dominated: smartphone features that give users what they want before they ask.

As part of its push, the company is currently trying to hire at least 86 more employees with expertise in the branch of artificial intelligence known as machine learning, according to a recent analysis of Apple job postings. The company has also stepped up its courtship of machine-learning PhD’s, joining Google, Amazon, Facebook and others in a fierce contest, leading academics say. …

While Apple helped pioneer mobile intelligence–it’s Siri introduced the concept of a digital assistant to consumers in 2011–the company has since lost ground to Google and Microsoft, whose digital assistants have become more adept at learning about users and helping them with their daily routines.

As users increasingly demand phones that understand them and tailor services accordingly, Apple cannot afford to let the gap persist, experts say. The iPhone generated almost two-thirds of Apple’s revenue in the most recent quarter, so even a small advantage for Android poses a threat.

“What seemed like science fiction only four years ago has become an expectation,” said venture capitalist Gary Morgenthaler, who was one of the original investors in Siri before it was acquired by Apple in 2010.•

Tags: Christopher Mims, Gary Morgenthaler, Julia Love, Steve Jobs, Tim Cook

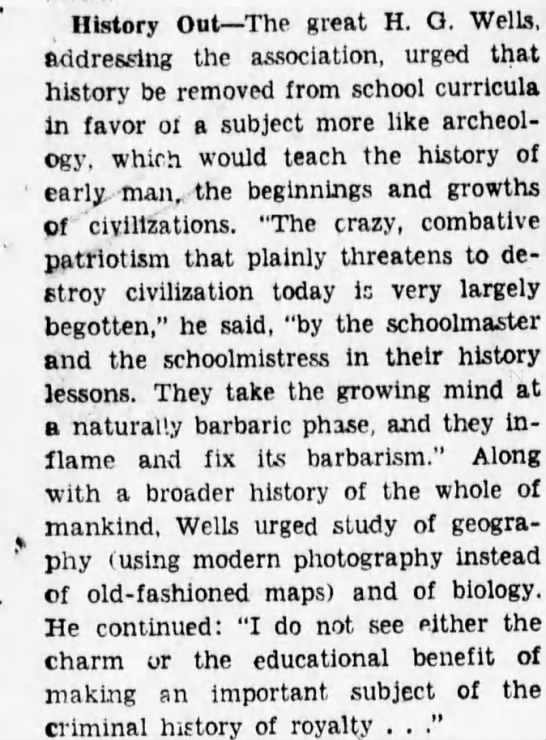

Perhaps it was his background in biology that made H.G. Wells believe that the differences among us were smaller than politics made them out to be.

The author, who in the 1890s wrote a series of classic novels of science fiction decades before that genre was named, believed schools were using the teaching of history to instill a dangerous strain of nationalism. He called for a shift to a less ideological view of the past. A brief article in the September 5, 1937 Brooklyn Daily Eagle recalls the marks that caused something of a sensation.

Tags: H.G. Wells

A little more of Jerry Kaplan and his new book, Humans Need Not Apply, is on display in Anthony Mason’s CBS News report “The Future of Work and Play.” Most of the piece will be familiar to those already thinking about the perplexing question of how a free-market economy can operate if it becomes a highly automated one, with discussion of driverless cars, algorithms thinning the ranks of blue- and white-collar workers alike, etc.

Most interesting is a visit to the Associated Press, which has begun relying on software to rapidly transform raw data into its inverted-triangle pieces, stories that can pass for human-level composition. Both the software makers and the AP say the innovation has complemented workers, not replaced them.

Still, NYU Professor Gary Marcus offers that a guaranteed minimum income from the state to citizens (likely through the taxation of capital) is ultimately the endgame of automation. View here.

Tags: Anthony Mason, Gary arcus, Philana Patterson, Robbie Allen

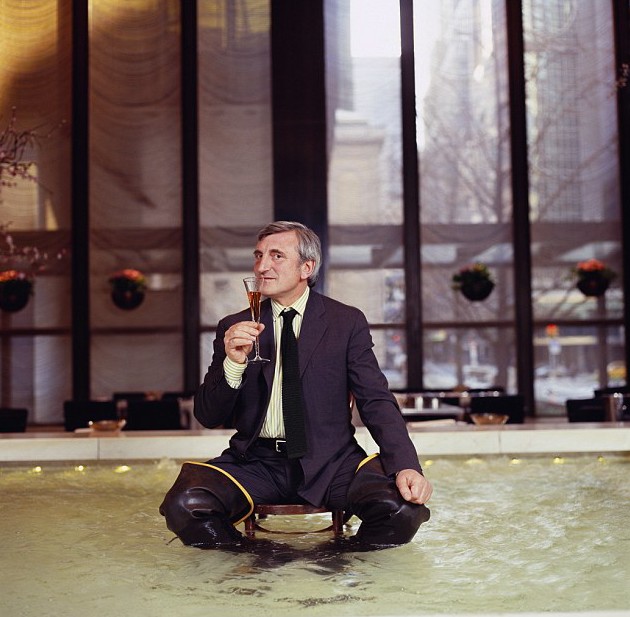

The band played on as the Titanic went down, and Julian Niccolini, Managing Partner of the Four Seasons, may likewise sink with the ship.

The hoary bastion of power lunches for privileged New Yorkers is soon to shutter, and Niccolini will either reopen it downtown or be doing a stretch in prison. That’s because the infamously “handsy” proprietor was arrested earlier this year for the sexual abuse of a woman who attended a party at the dated establishment.

In a very good GQ article, Robert Draper sees the fall of Four Seasons and its unruly ruler in terms of a generational shift, when a passé concept of white, male privilege ran up against new table manners.

An excerpt:

Whichever room you choose, you’ll notice two things. First is that the food is exorbitant (over $70 for some entrées) and often lackluster. A wild snapper with corn and guajillo sauce I had at lunch seemed a tired throwback to the nouveau-southwestern craze a couple of decades back. The ahi tuna burger from the bar menu was resoundingly inedible. Such trifles, as even restaurant critics who have consistently praised The Four Seasons acknowledge, are ultimately beside the point. You come here to bask in the spaciousness of what Jackie Onassis liked to call “the cathedral.” You come to take your rightful place in the pantheon and to be seen occupying that choice real estate. About a thousand faithful Four Seasons customers have a “house account”—meaning the bill typically goes directly to their companies. My old boss, former GQ editor-in-chief Art Cooper, had one such arrangement with The Four Seasons. According to Julian, Art spent about $200,000 a year at his favorite restaurant and never once saw a receipt—all the way up until June of 2003, when he rose from his corner booth, lumbered over to a barstool, succumbed to a stroke, and died at the age of 65.

That’s the second thing you’ll notice about The Four Seasons: Its clientele is, eh, not youthful. Still, it’s possible to look down from Siberia upon the octo- and nona-genarians and to imagine them as younger, hungrier, Bonfire of the Vanities versions of their present-day selves.

Julian Niccolini was present at their ascension, and they at his. On the subway to work each morning, he studied the Times, the Daily News, and Women’s Wear Daily to find out which celebrities were in town, what schemes the ultra-wealthy were up to, and who was cavorting with whom. The Grill Room’s seating chart became Julian’s interpretation of America’s pecking order. Even the richest of patrons would come to learn that this was Julian’s roost. As longtime customer Bill White, the CEO of the development firm Constellations Group, puts it, “The Four Seasons is one place where the customer isn’t always right.”

Julian’s reputation as a host persisted to the point that he was eventually penning columns in Gotham, Details, and the New York Observer, where he’d flatter this or that “beautiful” customer while gossiping about others (Bethenny Frankel urinating in a wine bucket). He also dispensed wisdom that ranged from the practical (like when to wear a linen suit) to the prurient (like what to do when a woman hits on you when your wife is standing nearby). At least a few uninitiated readers must have wondered just who this pretentious reptile was.•

Tags: Julian Niccolini, Robert Draper

The Gig Economy has been on the margins of America, but the fear is that it’s going mainstream. If technology, which hasn’t proved to be the worker’s friend, allows contingent employment to become the norm, we really aren’t arranged to handle that new reality. President Obama has been a champion of Labor, particularly in his second term, but he’s chastening elements of a system that may not continue. A piecemeal economy, if pervasive, will need fresh answers.

From Katie Johnston at the Boston Globe:

To be sure, technology has helped make workers more productive. But they are reaping few of the rewards that come from producing more in less time, and at lower costs. From 2000 to 2014, net productivity rose by nearly 22 percent, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington think tank. The gain in hourly compensation during that time? Less than 2 percent.

Nearly all the benefits of the surge in productivity have gone to top executives, in the form of bigger pay packages; to owners, as higher profits; and to investors, as better returns, the Economic Policy Institute said.

The rise of what’s being called the gig economy gives people the flexibility to work when and where they want — a great advantage for many workers. But few of these jobs come with benefits, or a guarantee of steady work. Many workers take them by necessity, not choice.

These types of arrangements are growing, and not only with so-called sharing economy firms such as the ride-hailing service Uber or TaskRabbit, which finds labor for daily chores. A recent study by the Government Accountability Office, an independent congressional watchdog agency, found that as many as 40 percent of employed Americans in 2010 were contingent workers — part-timers, temps, day laborers, or independent contractors — up from 35 percent in 2006.•

Tags: Katie Johnston

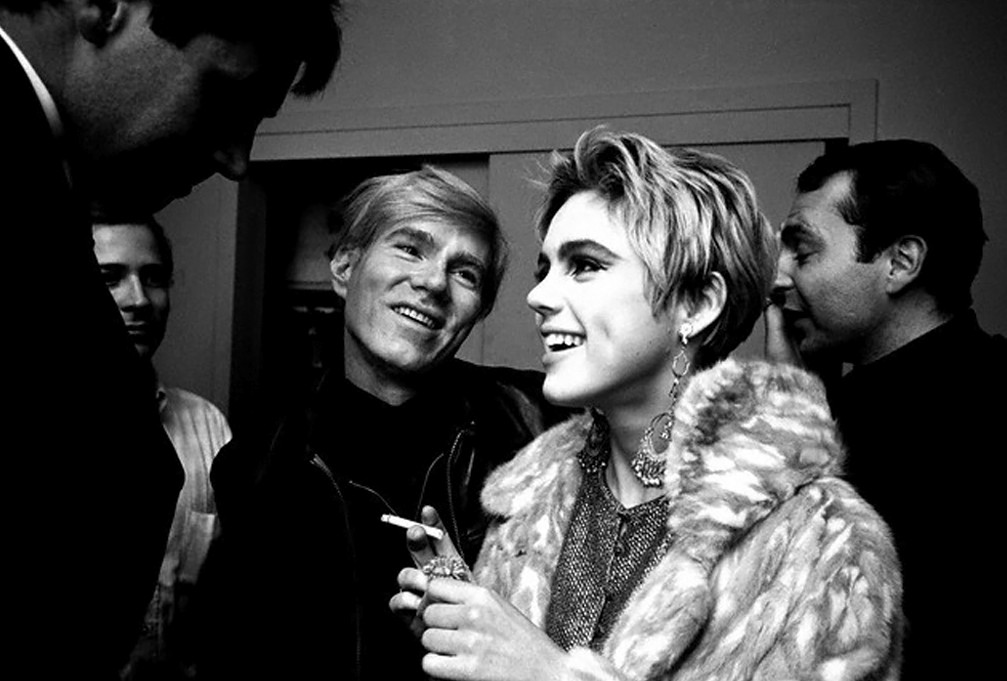

Paddy Chayefsky, that brilliant satirist, holds forth spectacularly on a 1969 episode of the Mike Douglas Show. It starts with polite chatter about the success of his script for Marty but quickly transitions into a much more serious and futuristic discussion. The writer is full of doom and gloom, of course, during the tumult of the Vietnam Era; his best-case scenario for humankind to live more peacefully is a computer-friendly “new society” that yields to globalization and technocracy, one in which citizens are merely producers and consumers, free of nationalism and disparate identity. Well, some of that came true. He joins the show at the 7:45 mark.

Andy Warhol refuses to speak during a 1965 appearance on Merv Griffin’s talk show, allowing a still-healthy-looking Edie Sedgwick to do handle the conversation. Not even the Pop Artist himself could have realized how correct he was in believing that soon just being would be enough to warrant stardom, that it wouldn’t matter what you said or if you said a thing, that traditional content would lose much of its value.

You know you had to have experienced the highest highs and lowest lows to see Preston Tucker in yourself, which is why he made such a perfect subject for Francis Ford Coppola. Below is a fun 1948 PR film that Tucker produced about his then-newest machine, a sedan nicknamed the “Tucker Torpedo,” which revolutionized the American automobile, before the SEC and rumors of wrongdoing forced it off the road.