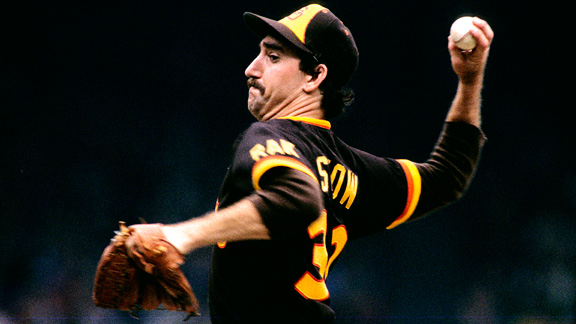

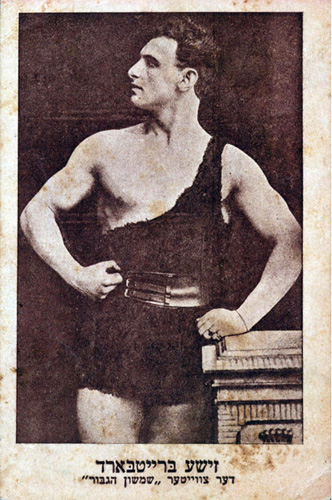

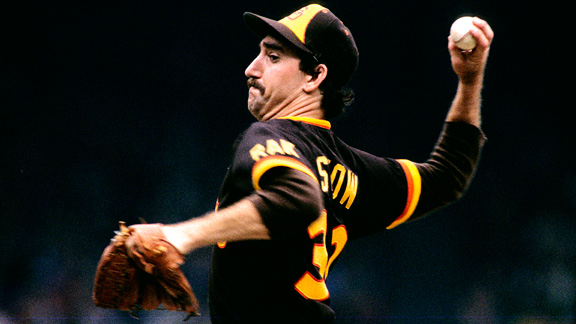

It was the strangest thing. In 1984, stories began to escape the San Diego Padres clubhouse about a trio of pitchers, Eric Show, Dave Dravecky and Mark Thurmond, who’d become devout members of the John Birch Society. Racist behavior that postseason directed at Claire Smith, an African-American sportswriter, brought more attention to the extreme politics of the Birchers.

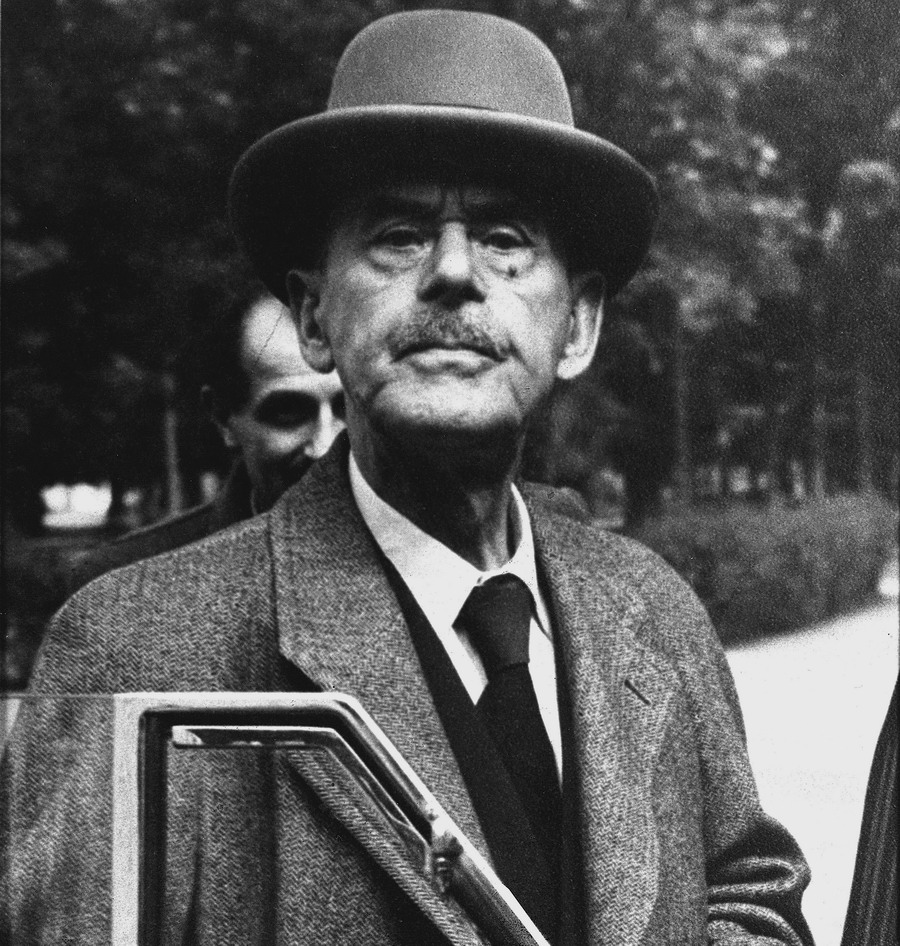

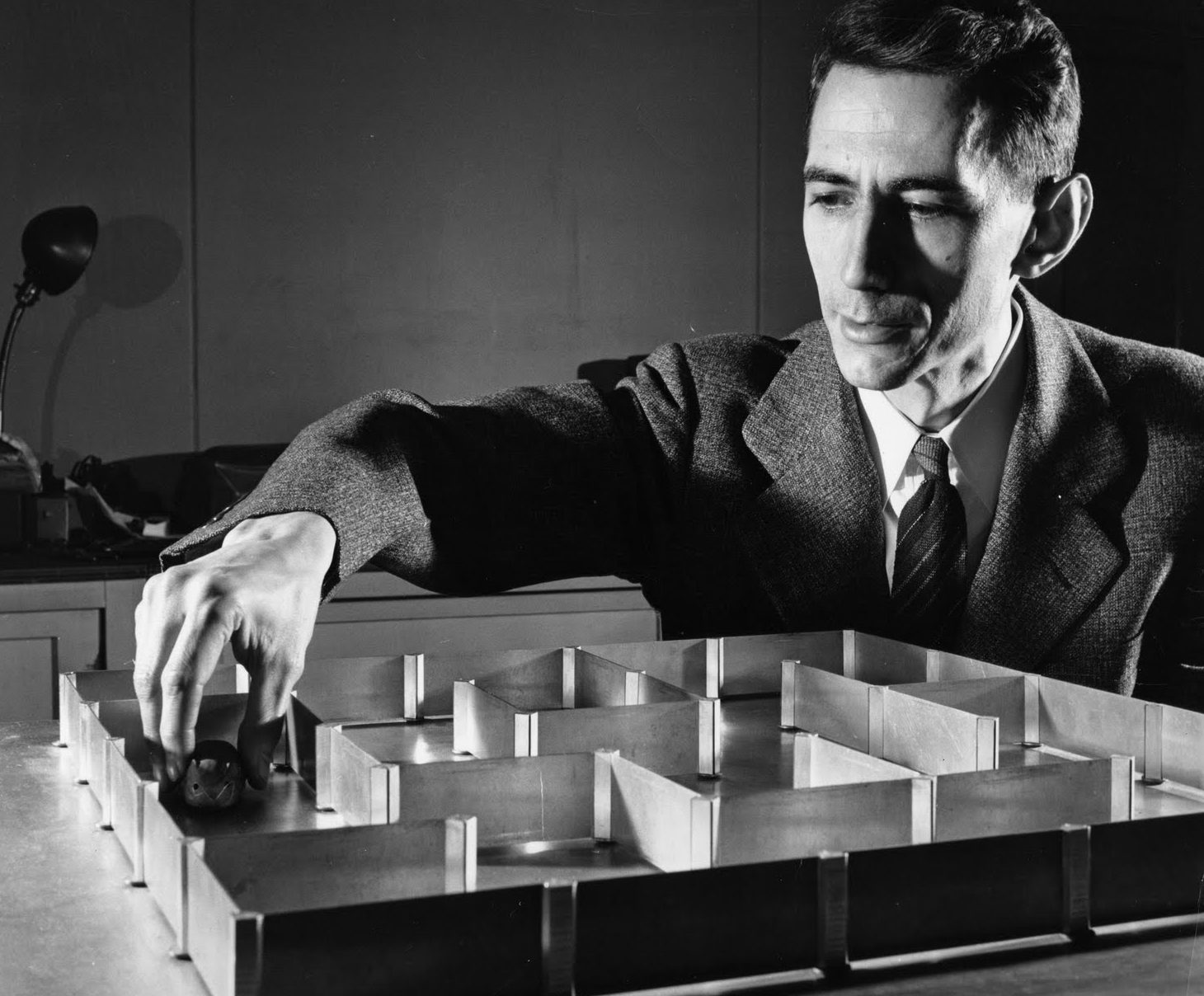

It all began with Show, a sort of baseball Bobby Fischer, a troubled nonconformist and deep thinker who couldn’t fit into wider society let alone the claustrophobic confines of a bullpen or dugout. He was a self-taught jazz musician ravenous for philosophy, physics, economics and history, a seeker of truth who wandered into an Arizona bookstore and headed down the wrong aisle. The pitcher picked up a volume about John Birch and became obsessed (though he always denied any racist leanings). Excerpts follow from two stories follow about his odd life and lonely death.

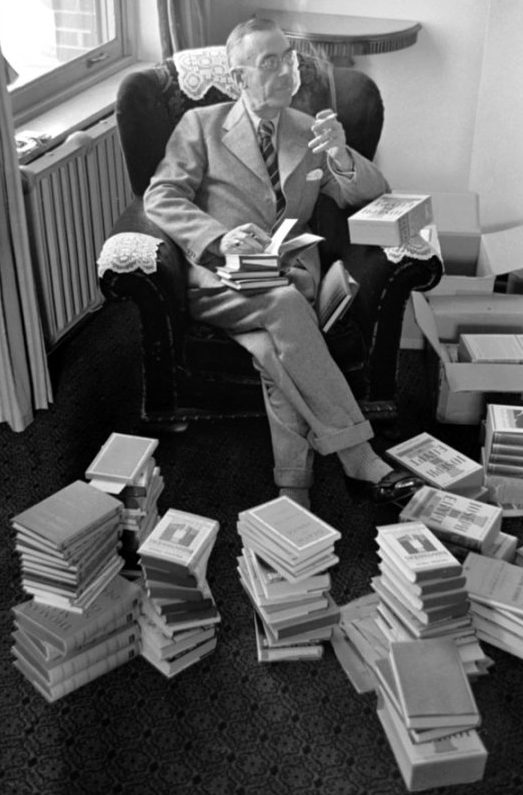

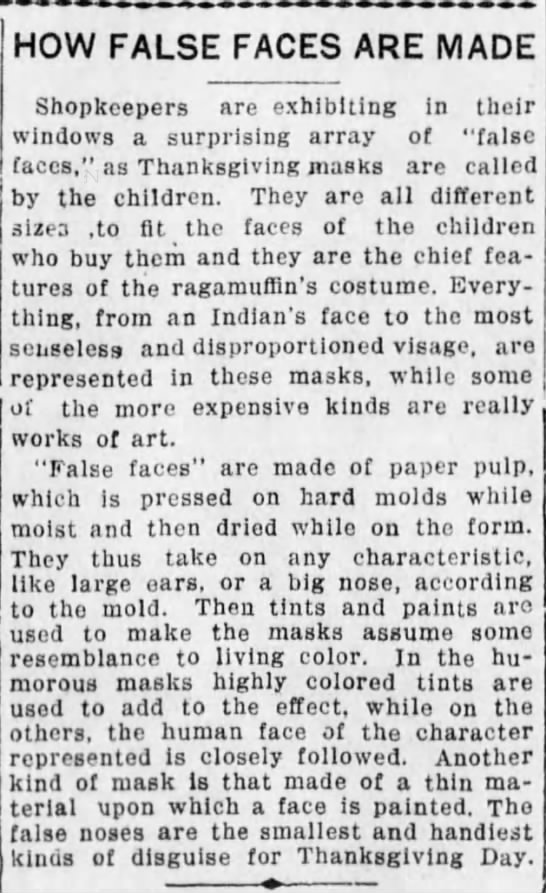

From “Baseball’s Thinking Man,” by Bill Plaschke, in the 1988 Los Angeles Times:

YUMA, Ariz. — Let’s play a game. What if some real smart people with a sense of humor–people who know nothing about baseball–one day decided to invent a very good baseball pitcher.

But after giving him an elbow and shoulder and all the usual stuff, what if they decided to get tricky?

What if they gave him a love for physics? A love for studying philosophers, historians and theorists? A love for writing classical jazz?

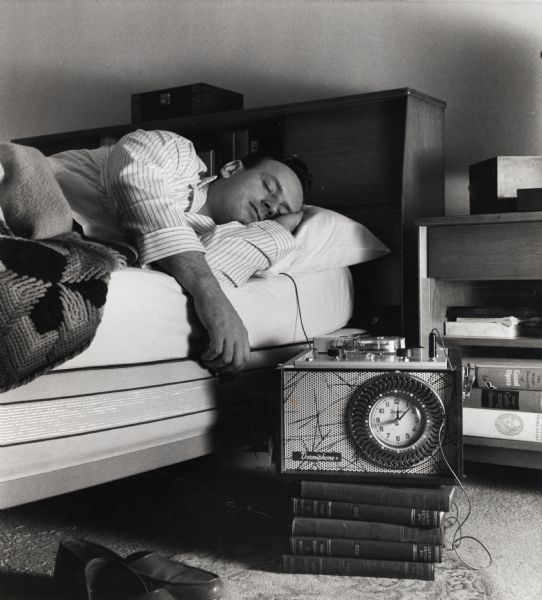

What if on road trips, while his friends are shopping and watching movies, he is in the basement of musty libraries trying to figure out why the Earth is round?

What if at home, while many players are at the ballpark several hours ahead of the required reporting time, he is still in his home, in his second-floor office, under a bright light, studying the effect of a new foreign government or ancient civilization?

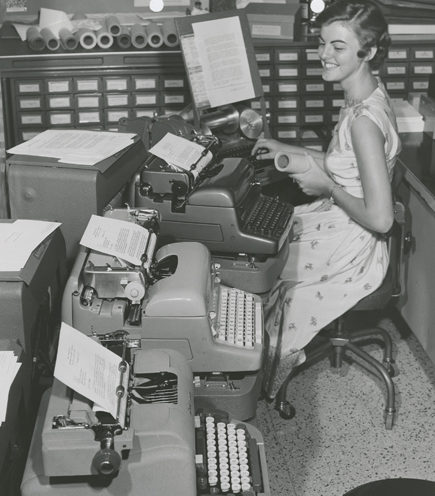

What if, before he wins 20 games, he records and produces his own record album, and co-stars in a movie? Finally, just to throw everybody off, what if they made him an open, verbal member of the ultra-conservative John Birch Society? What if . . .

Forget the what ifs. Such a pitcher exists. His name is Eric Show.

His six seasons have established him as one of the National League’s best pitchers and most unusual people.

Yet, after six seasons, another question is probably more applicable.

Why?

Why has he no close clubhouse friends? Why does everybody in there look at him so funny? Why do some think he’s selfish and arrogant? Why did some even take to calling him “Erica”? And why do things always seem to happen to him?

In 1984, his John Birch affiliation is uncovered when he is spotted passing out pamphlets at a fair, and black players think he doesn’t like them.

In 1985, he gives up Pete Rose’s record 4,192nd hit, but during the 10-minute celebration he sits on the mound, and now nobody likes him.

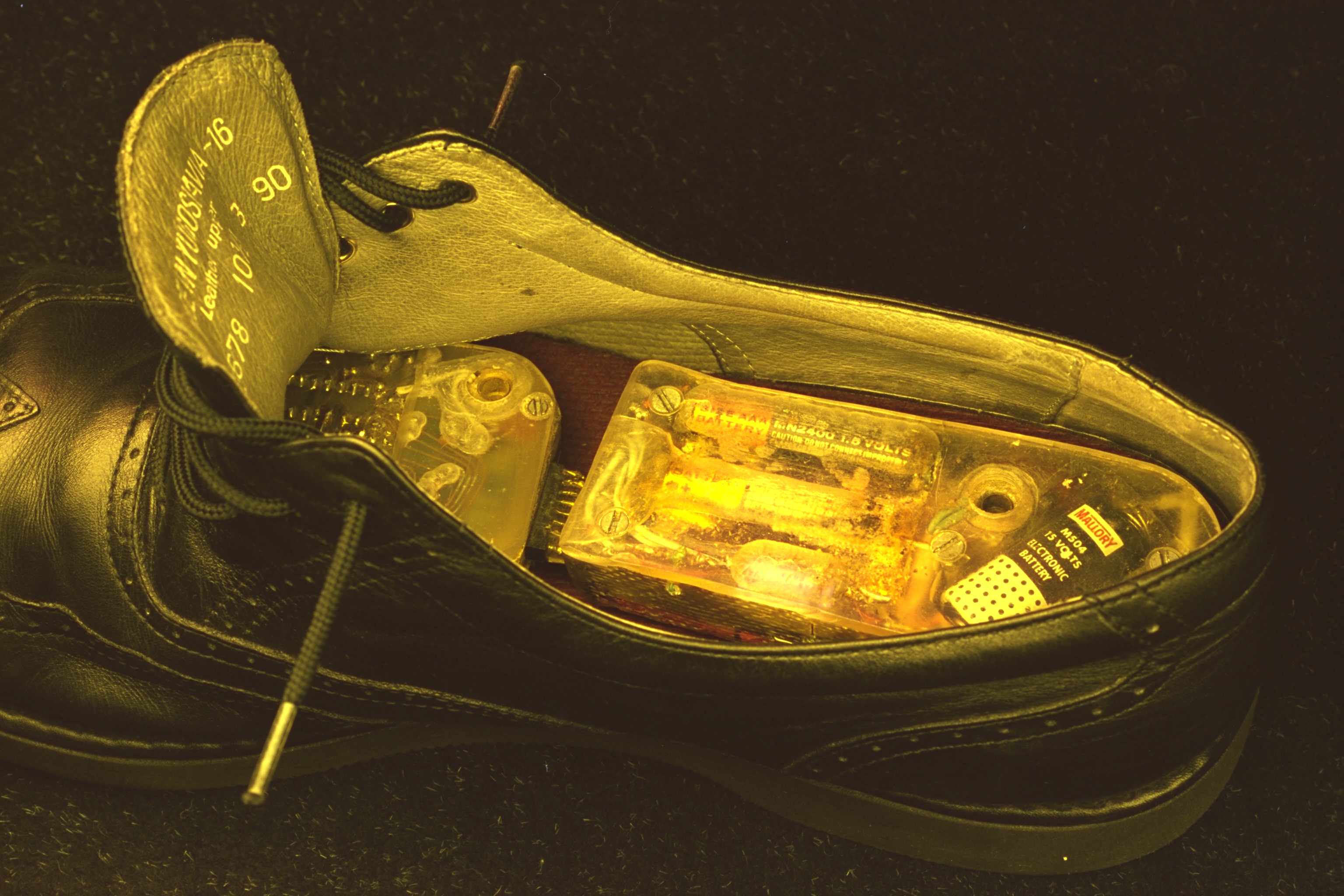

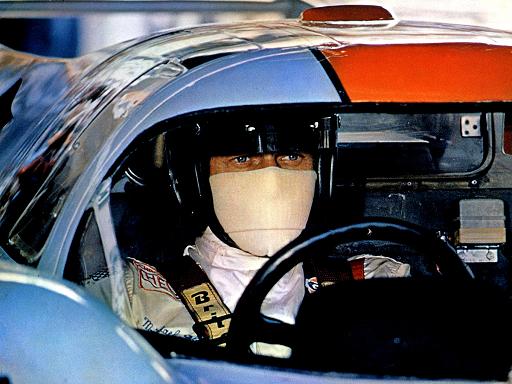

Last season, he hits the Chicago Cubs’ Andre Dawson in the head and must flee Wrigley Field fearing for his life. When he returns to that city this season, he has only half-jokingly claimed it will be in disguise.

Show, 31, enters the 1988 season in the final year of a $725,000 contract and at the crossroads of his baseball career.

Can he find enough peace to once again become the pitcher that won 15 games to help lead the Padres to the 1984 World Series?

Or will he continue twisting in the winds of discontent, like last season, when he went 8-16 despite a 3.84 earned-run average?

Either way, the Padres say he’s trying.

“There has been change in Eric just since the middle of last season,” Padre Manager Larry Bowa said. “In the clubhouse, away from the stadium. He’s really working at understanding and being understood.”

Show says he’s trying.

“As strange at it may seem, I have tried to be more a part of my baseball environment,” Show said carefully. “If I’m still off, it’s because I started way off.”

And whatever happens, only one thing is ever certain with Eric Show.

Something will get lost in the translation.•

From “Eric Show’s Solitary Life, and Death,” by Ira Berkow in the 1994 New York Times:

An autopsy released soon after by the coroner’s office said the cause of death was inconclusive, that is, there was no observable trauma or wounds to the body. A toxicology report would be coming in about two weeks. But in statements to the center’s staff, Show said that he was under the influence of cocaine, heroin and alcohol. He said he used four $10 bags of cocaine at about 7 that night, Tuesday night. “Didn’t like how I felt,” he said, adding that he then ingested eight $10 bags of heroin and a six-pack of beer.

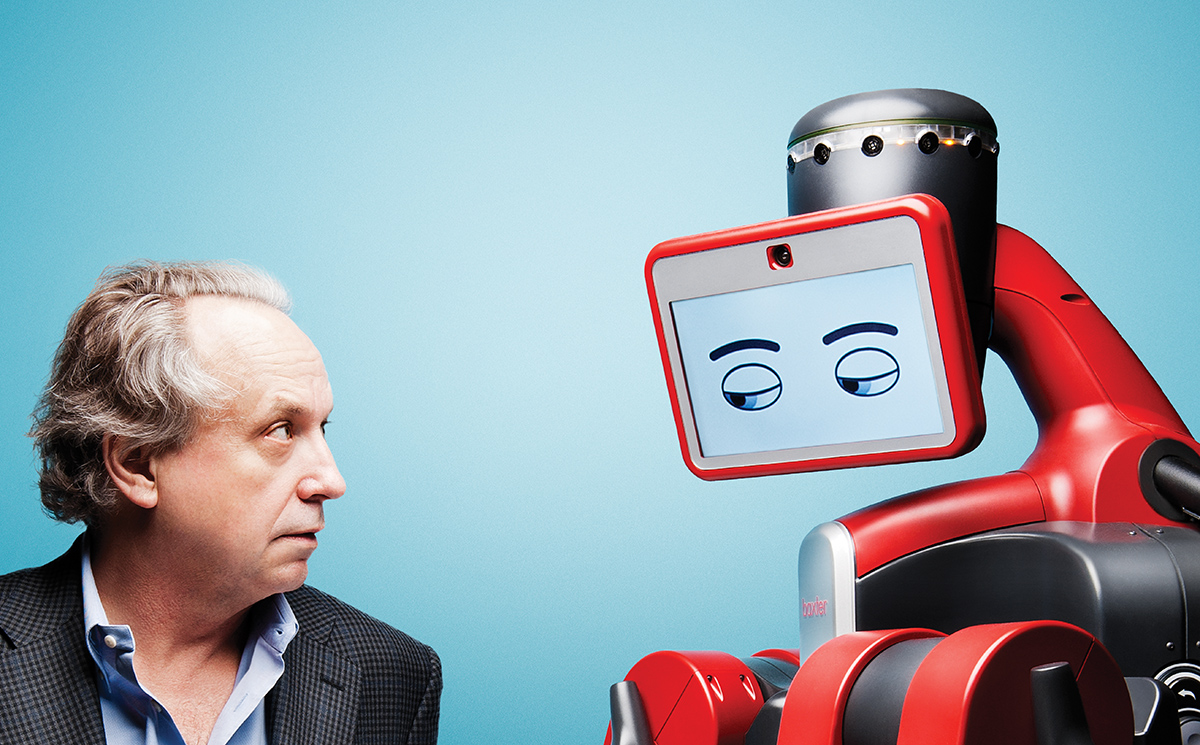

The questions about Eric Show’s death are no less difficult to answer than the ones about his life. Why was he so hard on himself, such an apparently driven individual? Why was he so compulsive, or at least passionate, about almost everything he undertook?

Show (the name rhymes with cow) was known as a highly intelligent, articulate man with broad interests that ranged from physics — his major in college — to politics to economics to music. “Eric didn’t fit the mold of the typical ballplayer,” said Tim Flannery, a former Padre teammate of Show’s. “Most ballplayers were like me then; we had tunnel vision. We weren’t interested in those other things.”

Show was a born-again Christian who regularly attended Sunday chapel services as a player and sometimes signed his autograph with an added Acts 4:12, which discusses salvation as coming only from belief in Jesus Christ.

He was an accomplished jazz guitarist. Sometimes after games on the road, he would beat the team back to the hotel and play lead guitar with the band in the lounge.

He was a member of the right-wing John Birch Society, a fact the baseball world was surprised to learn in August 1984 as the Padres moved toward their first and only division title.

And he was a successful businessman with real estate holdings, a marketing company and a music store, all of which kept him in expensive clothes, with a navy-blue Mercedes and a house in an affluent San Diego neighborhood.

But other elements seemed to intrude. And ultimately, the contradictions of the best and worst in American life became a disastrous mixture that defeated him.

Beyond Statistics, Just Who Was He?

For most baseball fans, Eric Show was a decent pitcher who had once been lucky enough to make it to the World Series. But to the people who were close to him, he was, in the end, someone they did not fully know.

“He led several lives, apparently,” said Arn Tellem, his agent at the time of his death.

To Joe Elizondo, his financial consultant, and Mark Augustin, his partner in a music store, and Steve Tyler, a boyhood friend from Riverside, Calif., where both were born and raised, Show was a charming, devoted friend and a caring man. “He would give you the shirt off his back,” Elizondo said. “And he did. I once told him how much I liked a shirt he was wearing, and he said, “Here, it’s yours.” He’d stop a beggar on the street and learn he was hungry and run to a diner and bring back a hot meal for him.”

To others, though, Show could seem selfish or arrogant.

And there were the drugs. Some said Show’s drug problems began when he took injections to relieve pain in his back after surgery, and he sought more and more relief. Others wondered if he had been taking drugs before he reached the major leagues.

He may also have begun taking drugs simply because he liked the challenge of being able to handle the dreaded substance. …

His death evoked memories of two strange scenes in Show’s life, one in 1992 and the other last year.

In the spring of 1992, Show was in training camp in Arizona with the A’s. He had signed a two-year contract with them in late 1990, and managed only a 1-2 record with them in 1991. Following several mornings in which he had reported late for workouts, he showed up with both hands heavily bandaged.

He explained that he had been chased by a group of youths and had to climb a fence, and had cut himself. But what was not reported was that the police later told club officials that Show had been behaving erratically in front of an adult book store, and fled when officers approached. They finally caught him trying to climb a barbed-wire fence.

Last July, he was caught by the police when running across an intersection in San Diego and screaming that people were out to kill him, and then begged the police to kill him. He was handcuffed, and while in the back seat of the police car, he kicked out the rear window. He was taken to the county mental hospital for three days of testing. Show had admitted “doing quite a bit of crystal methamphetamine.”

It was one more startling development, one more contradiction for an athlete who, in reference to his John Birch membership, once said: “I have a fundamental philosophy of less government, more reason, and with God’s help, a better world. And that’s it.”

Always Looking For Answers

Actually, it wasn’t it. Show, as a John Birch member, also denied that he was a Nazi or a racist. In fact, he had a Hispanic financial adviser, a Jewish lawyer and agent, and black friends in baseball and his music world. People from his first agent, Steve Greenberg, to Tony Gwynn, a black teammate, agreed that he was no bigot. “He joined the Birch Society because he thought it would provide answers to how the world works,” Tellem said. “He was always looking for answers.”

Show once said, “I’ve devoted my life to learning.” Asked what he was learning, he replied, “Learning everything.”•