Three months before we reached the moon, a moment when machines eclipsed, in a meaningful way, the primacy of humanity, National Geographic published the 1969 feature “The Coming Revolution in Transportation,” penned by Frederic C. Appel and Dean Conger. The article prognosticated some wildly fantastical misses as any such futuristic article would, but it broadly envisioned the next stage of travel as autonomous and, perhaps, electric.

Three months before we reached the moon, a moment when machines eclipsed, in a meaningful way, the primacy of humanity, National Geographic published the 1969 feature “The Coming Revolution in Transportation,” penned by Frederic C. Appel and Dean Conger. The article prognosticated some wildly fantastical misses as any such futuristic article would, but it broadly envisioned the next stage of travel as autonomous and, perhaps, electric.

The two excerpts I’ve included below argue that tomorrow’s transportation would in, one fashion or another, remove human hands from the wheel. The second passage particularly relates to the driverless sector of today. Interesting that we’re skipping the top-down step of building “computer-controlled” or “automated” highways, something suggested as necessary in this piece, as an intensive infrastructure overhaul never materialized. We’re attempting instead to rely on visual-recognition systems and an informal swarm of gadgets linked to the cloud to circumvent what was once considered foundational.

“People Capsule”: Dial Your Destination

Everywhere I found signs that a revolution in transportation is on the way.

The automobile you drive today could probably move at 100 miles an hour. But you average closer to 10 as you travel our clogged city streets.

Someday, perhaps in your lifetime, it could be like this….

You ride toward the city at 90 miles an hour, glancing through the morning newspaper while your electrically powered car follows its route on the automated “guideway.”

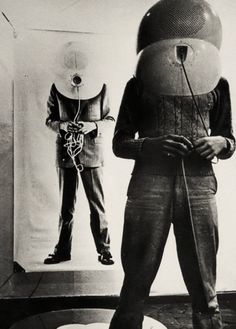

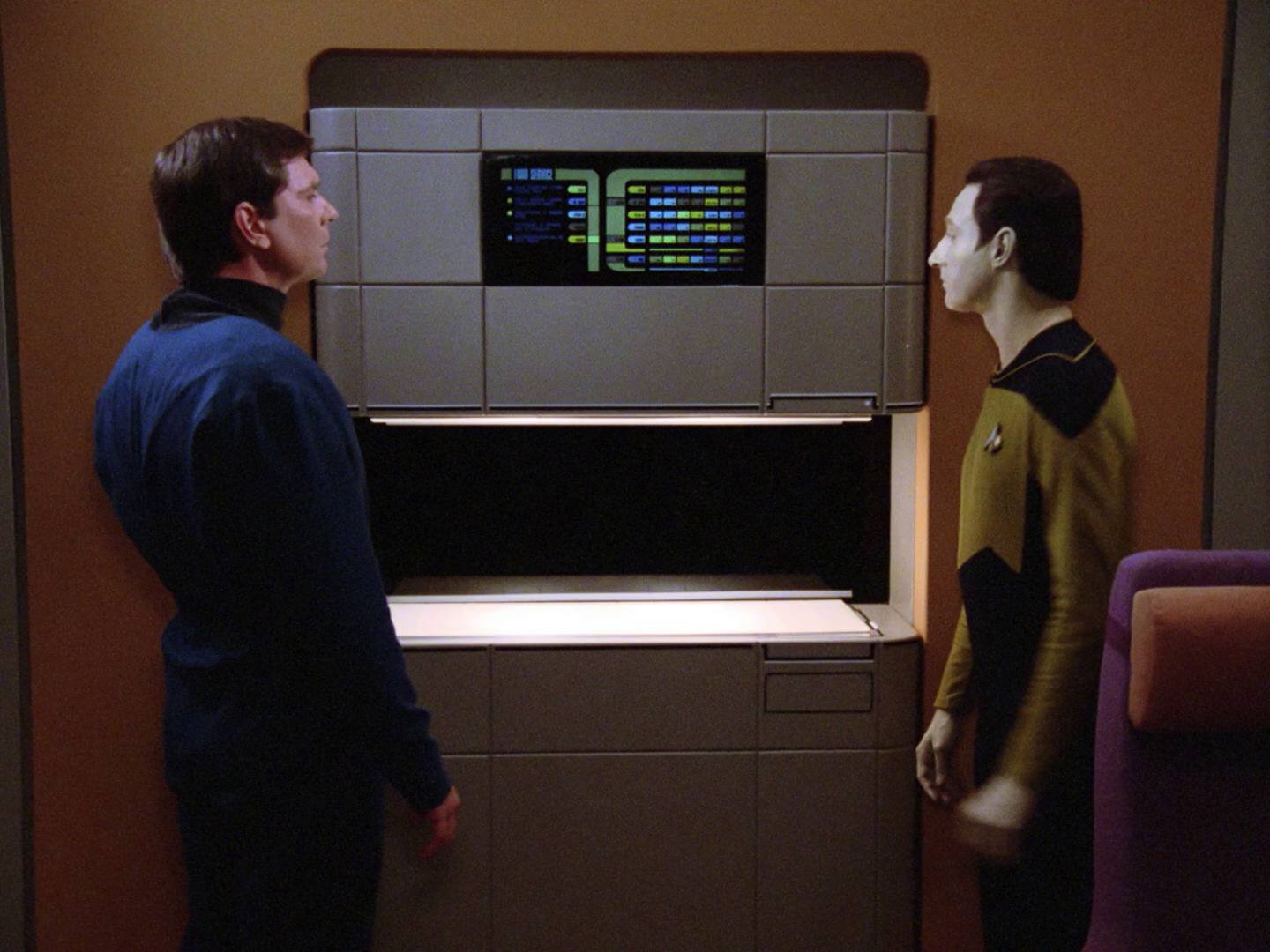

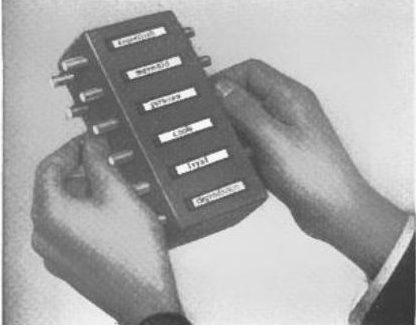

You leave your car at the city’s edge–a parklike city without streets–and enter on the small plastic “people capsules” waiting nearby. Inside, you dial your destination on a sequence of numbered buttons. Then you settle back to reading your paper.

Smoothly, silently, your capsule accelerates to 80 miles an hour. Guided by a distant master computer, it slips down into the network of tunnels under the city–or into tubes suspended above it–and takes precisely the fastest route to your destination.

Far-fetched? Not at all. Every element of that fantastic people-moving system is already within range of our scientists’ skills.•

Car-trunk Computer Issues Orders

Car-trunk Computer Issues Orders

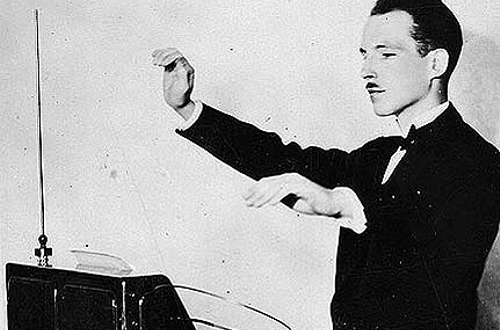

Consider automated cars–and when you do, look at the modern automobile. Think of the rapid increase, in the past decade, of electric servomechanisms on automobiles. Power steering, antiskid power brakes, adjustable seats, automatic door locks, automatic headlight dimmers, electronic speed governors, self-regulated air conditioning.

Detroit designers, already preparing for the day your vehicle will drive itself, are getting practical experience with the automatic devices on today’s cars. When more electric devices are added and the first computer-controlled highways are built, the era of the automated car will be here.

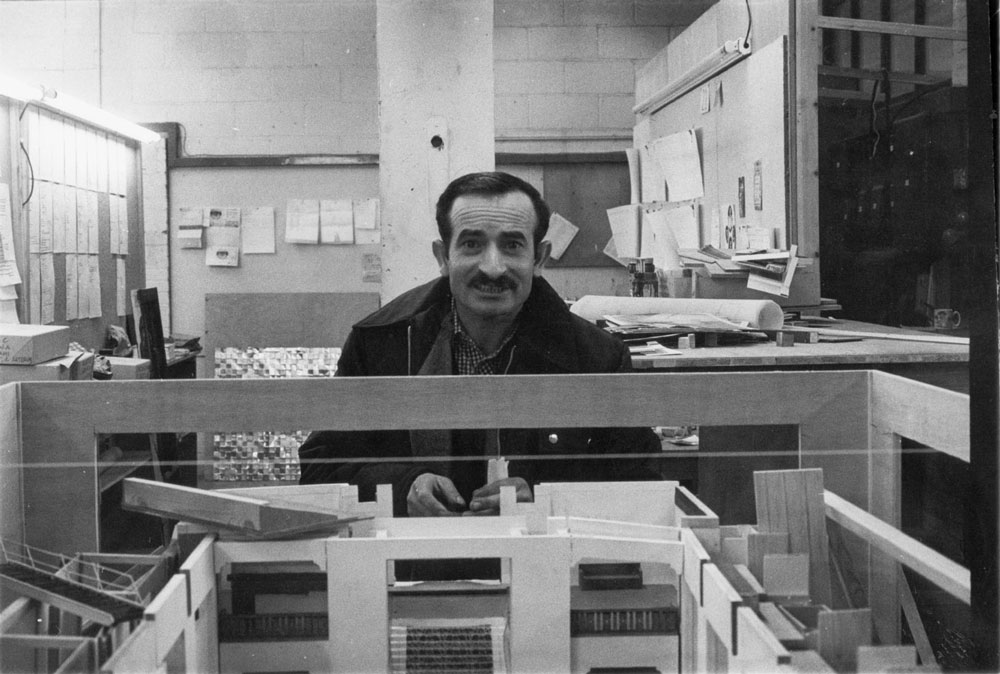

At the General Motors Technical Center near Detroit, I drove a remarkable vehicle. It was the Unicontrol Car, one step along the way to the automated family sedan.

In the car a small knob next to the seat (some models have dual knobs) replaced steering wheel, gearshift lever, accelerator and brake pedal.

Moving that knob, I learned, sends electronic impulses back to a sort of “baby computer” in the car’s trunk. The computer translates those signals into action by activating the proper servomechanism–steering motor, power brakes, or accelerator.

Highways May Take Over the Driving

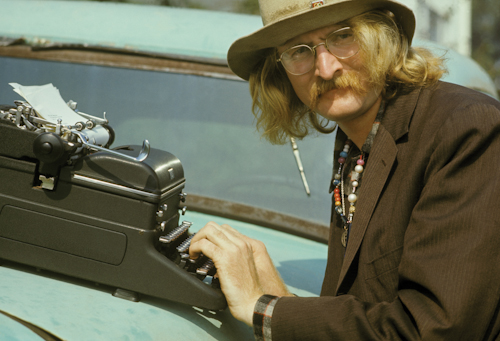

Simple and ingenious, I thought, as I slid into the driver’s seat. Gingerly I pushed the knob forward. Somewhere, unseen little robots released the brake and stepped on the gas.

So far, so good. Now I twitched the knob to the left–and very nearly made a 35-mile-an-hour U-turn!

But after a few minutes of practice, I found that the strange control method really did feel comfortably logical. I ended my half-hour test drive with a smooth stop in front of a Tech Center office building and headed upstairs to call on Dr. Lawrence R. Hafstad, GM’s Vice President in Charge of Research Laboratories.

The Unicontrol Car–a research vehicle built to test new servomechanisms–is easy to drive. Still, it does have to be driven. I asked Dr. Hafstad about the proposed automated highways that would relieve the driver of all responsibilities except that of choosing a destination.

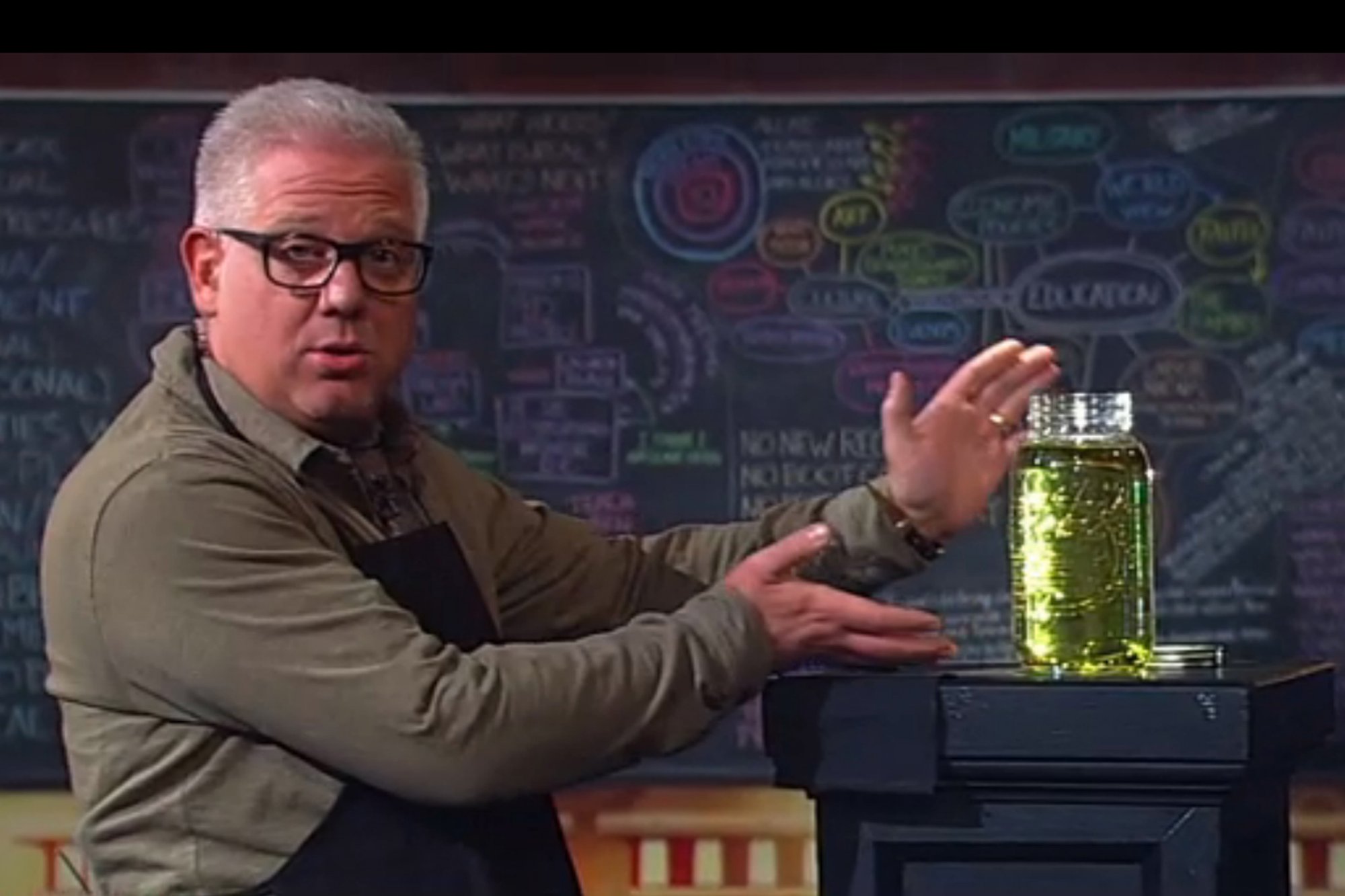

“Automated highways–engineers call them guideways–are technically feasible today,’ Dr. Hafstad answered. “In fact, General Motors successfully demonstrated an electronically controlled guidance system about ten years ago. A wire was embedded in the road, and two pickup coils were installed at the front of the car to sense its position in relation to that wire. The coils sent electrical signals to the steering system, to keep the vehicle automatically on course.

“More recently, we tested a system that also controlled spacing and detected obstacles. It could slow down an overtaking vehicle–even stop it, until the road was clear!”

Other companies are also experimenting with guideways. In some systems, the car’s power comes from an electronic transmission line built into the road. In others, vehicles would simply be carried on a high-speed conveyor, or perhaps in a container. Computerized guidance systems vary, too.

“Before the first mile of automated highway is installed,” Dr. Hafstad pointed out, “everyone will have to agree on just which system is to be used.”•