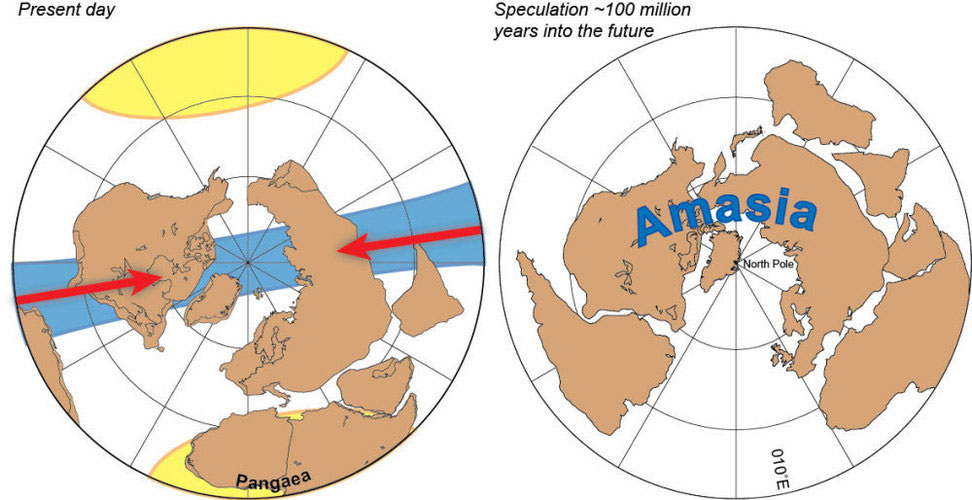

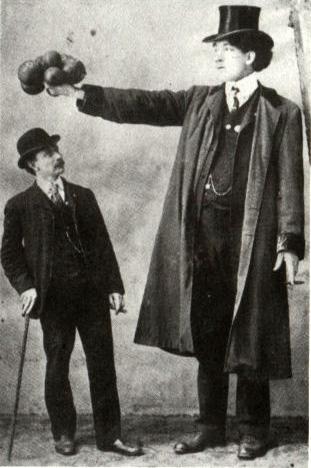

Robert E. Peary, legendary Arctic explorer, may or may not have been the first person to reach the North Pole, but he sure spent a lot of time in that particular neighborhood. (In fact, his only daughter, Marie, nicknamed “Snow Baby,” was even born in the Arctic.) These classic photos of the adventurer, taken by Benjamin B. Hampton, were shot the year that Peary claimed to have arrived at his greatest triumph. Here’s an excerpt from a book Peary wrote in which he describes–from a Caucasian outsider’s point of view–medicine, death and burial among the indigenous peoples:

“There are no chiefs among these people, no men in authority; but there are medicine men who have some influence. The angakok is generally not loved—he knows too many unpleasant things that are going to happen, so he says. The business of the angakok is mainly singing incantations and going into trances, for he has no medicines. If a person is sick, he may prescribe abstinence from certain foods for a certain number of moons; for instance, the patient must not eat seal meat, or deer meat, but only the flesh of the walrus. Monotonous incantations take the place of the white man’s drugs. The performance of a self-confident angakok is quite impressive—if one has not witnessed it too many times before. The chanting, or howling, is accompanied by contortions of the body and by sounds from a rude tambourine, made from the throat membrane of a walrus stretched on a bow of ivory or bone. The tapping of the rim with another piece of ivory or bone marks the time. This is the Eskimo’s only attempt at music. Some women are supposed to possess the power of the angakok—a combination of the gifts of the fortune teller, the mental healer, and the psalmodist, one might say.

Once, years ago, my little brown people got tired of an angakok, one Kyoahpahdo, who had predicted too many deaths; and they lured him out on a hunting expedition from which he never returned. But these executions for the peace of the community are rare.

Their burial customs are rather interesting. When an Eskimo dies, there is no delay about removing the body. Just as soon as possible it is wrapped, fully clothed, in the skins which formed the bed, and some extra garments are added to insure the comfort of the spirit. Then a strong line is tied round the body, and it is removed, always head first, from the tent or igloo, and dragged head first over the snow or ground to the nearest place where there are enough loose stones to cover it. The Eskimos do not like to touch a dead body, and it is therefore dragged as a sledge would be. Arrived at the place selected for the grave, they cover the corpse with loose stones, to protect it from the dogs, foxes, and ravens, and the burial is complete.

According to Eskimo ideas, the after-world is a distinctly material place. If the deceased is a hunter, his sledge and kayak, with his weapons and implements, are placed close by, and his favorite dogs, harnessed and attached to the sledge, are strangled so that they may accompany him on his journey into the unseen. If the deceased is a woman, her lamp and the little wooden frame on which she has dried the family boots and mittens are placed beside the grave. A little blubber is placed there, too, and a few matches, if they are available, so that the woman may light the lamp and do some cooking in transit; a cup or bowl is also provided, in which she may melt snow for water. Her needle, thimble, and other sewing things are placed with her in the grave.”

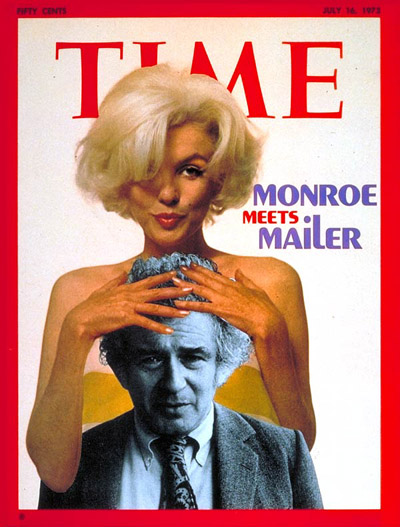

“Snow Baby.”