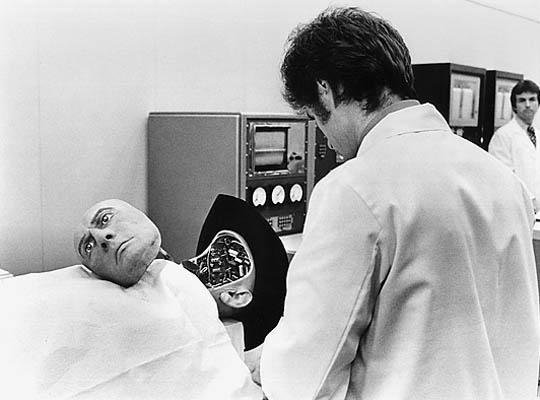

“A more repulsive sight to any lover of the ‘human form divine’ it would be difficult to imagine.”

Isaac Sprague was a nineteenth-century dime museum performer who was billed as the “Living Skeleton.” He had some sort of progressive muscular disease and was invited into classrooms as well as sideshows, so that medical students could study his malady. Such a visit to academia was covered by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in truly insulting fashion in its November 25, 1883 issue, which was published four years before his death. An excerpt:

“Isaac Sprague, who is usually advertised in museums or traveling shows as the living skeleton, was exhibited yesterday to the students of the Rush Medical College, and was made the subject of a lecture by Dr. Henry M. Lyman. Several hundred students filled the tiers of seats that rose above each other to the roof of the amphitheatre, and in the small semicircle below sat the skeleton. A skeleton he was, indeed, for there did not appear to be a single vestige of flesh on his body, and the skin was drawn tightly over the bones. He wore a pair of trunks, leaving his legs, chest and arms nude, and a more repulsive sight to any lover of the ‘human form divine’ it would be difficult to imagine. The man’s spine was curved to one side and there was a tremulous pulsation in the neck over the right shoulder that produced an irritating effect upon an observer’s nerves. Sprague’s face is not attenuated in comparison with his body, and his neck seems to preserve some muscular tissues, but all the remainder is a mass of living articulated bones.

The skeleton said that he was forty-two years old and had been suffering from progressive muscular atrophy for thirty years. ‘Cases such as this,’ said the lecturer, ‘generally run their course in five years, and few have been known to exceed twenty years. It is safe to say that there is no case like the present one on record.’

The skeleton said that he was forty-two years old and had been suffering from progressive muscular atrophy for thirty years. ‘Cases such as this,’ said the lecturer, ‘generally run their course in five years, and few have been known to exceed twenty years. It is safe to say that there is no case like the present one on record.’

‘Have you suffered much?’ the doctor asked.

‘No,’ said the skeleton in a voice almost as thin as his legs. ‘I have had almost no rheumatic pains; have suffered no loss of sleep; I can eat three hearty meals a day, and have been married twice and now have three children.’

The skeleton, in conclusion, told the students that he now weighs fifty pounds, which was half what he weighed when the disease began. He said, in an incidental and humorous way, that his wife weighed 172 pounds. He himself is five feet five and one half inches in height, and his boy, weighing 125 pounds, can carry his father about like a child.”