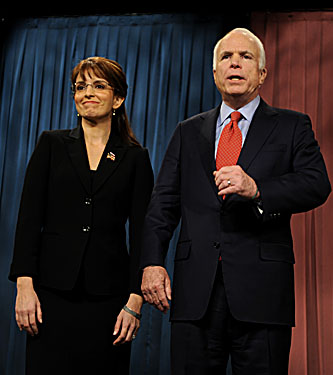

No one outside of NYC literary circles may care about this, but over the last couple of weeks there’s been a debate in that world about the value of satire and its pesky little sibling, snark. It started with Tom Scocca’s Gawker essay “On Smarm” which argues that those opposed to impolite humor are really just trying to protect an unfair status quo that profits them. A few days later, Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker blog post “Being Nice Isn’t Really So Awful,” retorted that satire actually aids the powerful even if it’s aimed at them. Two quick thoughts starting in reverse order with Gladwell’s piece.

1) There’s a gigantic pothole in Gladwell’s reasoning that satire is ineffectual and that more serious criticism is preferable. He quotes a famous Peter Cook line (via a Jonathan Coe essay) about “those wonderful Berlin cabarets which did so much to stop the rise of Hitler and prevent the outbreak of the Second World War.” Um, no, stage satire didn’t stop the Nazis, but you know what else didn’t prevent that horror? Serious criticism, op-eds and solemn political speeches. German resistance groups were likewise unable to stop Hitler’s ascent. Does that mean that serious criticism and protest are meaningless? Of course not. They just sadly didn’t work in this case. But they are good and useful things that have helped open eyes, hearts and minds in many other moments and so has humor.

Satire isn’t the main action but a call to action. It’s the weather report that tells us it’s pouring outside before most of us have yet taken notice of a cloud in the sky. (Though, no, it won’t unfold your umbrella for you.) It’s the first salvo, not the coup de grâce. It’s written about the present with an eye toward the future. And it doesn’t need to deflate dissent unless it’s written that way, and the best of it is not. There’s no measurement to quantify how much satire has helped accomplish, but it seems a trusty tool in the long march toward progress.

Ultimately, I think Gladwell is trying to knock down what he feels is a false narrative with a false one of his own.

2) That being said, I take an argument that there’s a dangerous effort to upend satire with the same seriousness as I take the so-called “War on Christmas.” Yes, there are some hypersensitive souls who confuse a punchline for an actual punch, but there has never been more satire or snark in the country than now, nor more channels, stages and outlets to practice this “dark” art. It’s under no threat and an argument that worries about it excessively seems hysterical. There is certainly no consensus against biting criticism. It, not smarm, is actually the hallmark of our times. I think that’s a reassuring thing.•

The opening of Scocca’s piece:

“Last month, Isaac Fitzgerald, the newly hired editor of BuzzFeed’s newly created books section, made a remarkable but not entirely surprising announcement: He was not interested in publishing negative book reviews. In place of ‘the scathing takedown rip,’ Fitzgerald said, he desired to promote a positive community experience.

A community, even one dedicated to positivity, needs an enemy to define itself against. BuzzFeed’s motto, the attitude that drives its success, is an explicit ‘No haters.’ The site is one of the leading voices of the moment, thriving in the online sharing economy, in which agreeability is popularity, and popularity is value. (Upworthy, the next iteration, has gone ahead and made its name out of the premise.)

There is more at work here than mere good feelings. ‘No haters’ is a sentiment older and more wide-reaching than BuzzFeed. There is a consensus, or something that has assumed the tone of a consensus, that we are living, to our disadvantage, in an age of snark—that the problem of our times is a thing called ‘snark.'”

From Gladwell:

“Earlier this year, in the London Review of Books, the English novelist Jonathan Coe published an essay titled ‘Sinking Giggling into the Sea.’ It is a review of a book about the mayor of London, Boris Johnson. And in the course of evaluating Johnson’s career, Coe observes that the tradition of satire in English cultural life has turned out to be profoundly conservative. What began in an anti-establishment spirit, he writes, ends up dissipating into a ‘culture of facetious cynicism.’ Coe quotes the comedian Peter Cook—’Britain is in danger of sinking giggling into the sea’—and continues:

The key word here is ‘giggling’ (or in some versions of the quotation, ‘sniggering’). Of the four Beyond the Fringe members, it’s always Peter Cook who is described as the comic genius, and like any genius he fully (if not always consciously) understood the limitations of his own medium. He understood laughter, in other words – and certainly understood that it is anything but a force for change. Famously, when opening his club, The Establishment, in Soho in 1961, Cook remarked that he was modelling it on ‘those wonderful Berlin cabarets which did so much to stop the rise of Hitler and prevent the outbreak of the Second World War’.

‘Laughter,’ Coe concludes, ‘is not just ineffectual as a form of protest … it actually replaces protest.’

Coe and Scocca are both interested in the same phenomenon: how modern cultural forms turn out to have unanticipated—and paradoxical—consequences. But they reach widely divergent conclusions. Scocca thinks that the conventions of civility and seriousness serve the interests of the privileged. Coe says the opposite. Privilege is supported by those who claim to subvert civility and seriousness. It’s not the respectful voice that props up the status quo; it is the mocking one.”