“I have my manias, and I impose them.”

Italo Balbo, Mussolini’s Air Minister, created an experimental office environment that was a technocrat’s dream, humming with gizmos, even if it shared some of the fascist tendencies of his politics. There was an Automat-style lunchroom and a tubing system that delivered coffee to desks, which was wonderful provided you weren’t aging, sickly or disabled. Then you weren’t allowed to work there. An article from the February 23, 1933 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“Paris–Fascist Air Minister Italo Balbo of Italy, soon to fly to America with 20 planes, has hot coffee shot up to his office through pneumatic tubes. So in fact do all the 2,000 clerks and other personnel of his ministry.

This is but one of the fantasies that the 36-year-old, prematurely bearded air minister (possible successor to Mussolini) has incorporated in the newest of Rome’s government buildings.

In spite of his youth he is probably the dean of the world’s air ministers, since he is in his sixth year of office. To Claude Blanchard whom he showed around the building, he stated that he had deep dislike for ordinary government offices.

‘I have my manias, and I impose them,’ he laughed. ‘There is not a drawer in the building.’ He explained that his first four years in politics gave him a horror of desk drawers.

Blanchard describes the ministry as a combination of ‘factory, museum, laboratory, gymnasium, restaurant, bank, university and storehouse.’

Every desk has a telephone and a pneumatic tube such as department stores use to shoot change from customer to cashier and back. The elevators are endless chain affairs which never stop; and on and off which passengers leap while they are in motion.

No Gray Hairs In Sight

There are no paralytics or rheumatics in the ministry. Blanchard said that he did not see one gray hair.

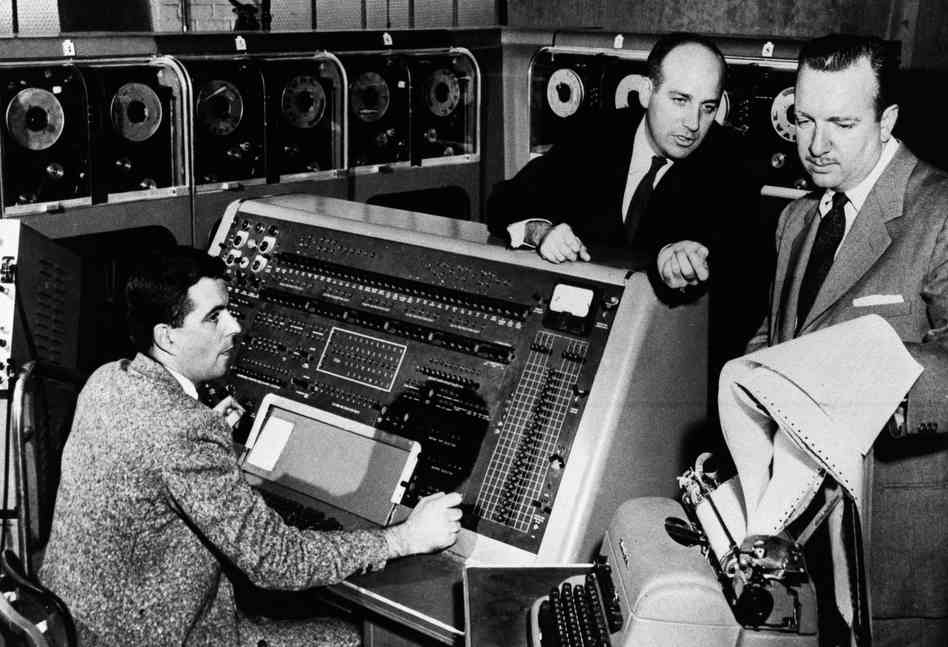

Balbo, while visiting Chicago, 1933.

Balbo’s own office is a wide bright room, the walls of which are decorated with huge maps painted in the seventeenth century manner. While they were talking something like a steamboat whistle blew; and the minister invited the guest to lunch.

After a descent in the non-stop elevators they came out in an immense stand-up lunch room, in which everybody from the minister down to the workmen in aprons and overalls eat at once. They all pay for it, the minister and upper ranks paying 32 cents and the men in overalls seven. Forty-five minutes are allowed for lunch. Blanchard, between Balbo and a high staff officer, lined up at one of the long nickel and porcelain shelves, opened the small nickeled doors in front of him. There, kept hot by electricity, was the whole meal.

It was not a completely standardized meal. The menu had been circulated earlier in the morning and everybody had shot back his order by pneumatic tube.

In fifteen minutes the lunch was over and everybody flowed around to a colossal bar filled with glittering coffee ‘espresso’ machines. Each made his own coffee; and it was there that Balbo showed with some pride the system by which the clerks get coffee in their offices without leaving their desks. A clerk shoots an order down the tube with his desk number on it; and in a moment a sealed bottle with the coffee in it plops out of the tube.

It is a good ministry to work in. It closes at a quarter to four.”