New Texas Monthly EIC Tim Taliaferro was quoted in the Columbia Journalism Review as saying that “Texans don’t care about politics,” so the publication was moving in a new and softer direction. Oil itself couldn’t be more Texan than politics, so the editor quickly found himself sliding around in a slick and backpedaled as hastily as possible. Who knows what the future holds for the legendary long-form magazine, but it doesn’t sound hopeful.

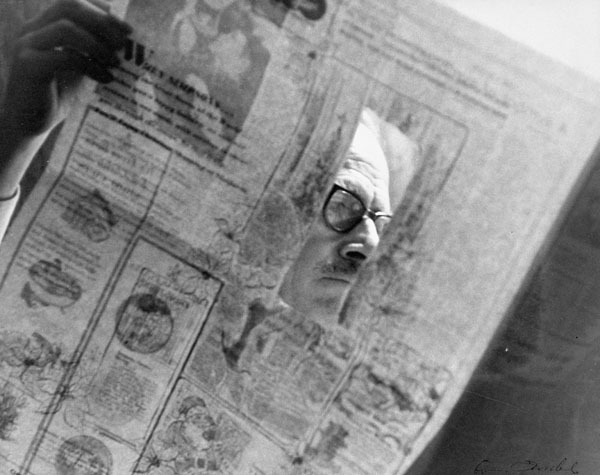

One of the linchpins of Texas Monthly reportage–and, more broadly, of the New Journalism of the ’60s and ’70s–was Gary Cartwright, a Dallas-Fort Worth gonzo who just passed away. The hard-drinking, freewheeling writer was an exquisite prose producer and confidante of Jack Ruby, who spent many of the days leading up to his murder of Lee Harvey Oswald planted, along with his stripper girlfriend Jada, on Cartwright’s couch. The scribe wrote of the two-bit assassin who dreamed of global fame: “He didn’t make history; he only stepped in front of it. When he emerged from obscurity into that inextricable freeze-frame that joins all of our minds to Dallas, Jack Ruby, a baldheaded little man who wanted above all else to make it big, had his back to the camera.”

From Manny Fernandez’s New York Times obituary of the writer:

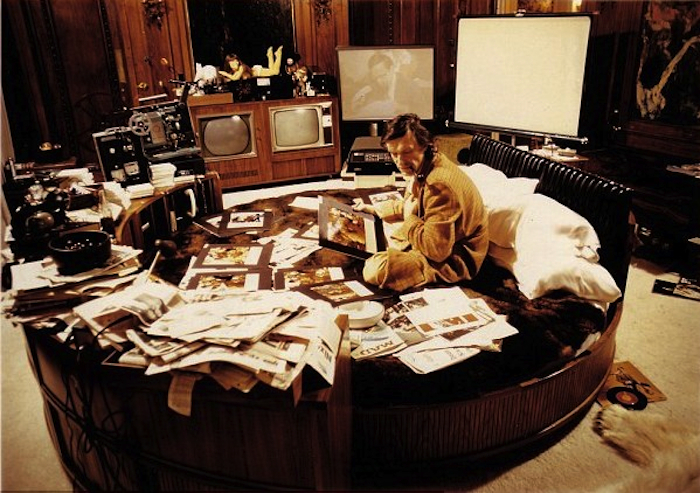

In the 1960s and ’70s Mr. Cartwright belonged to a group of writers — including Mr. Shrake, Dan Jenkins, Billy Lee Brammer and Larry L. King, one of the writers of the hit Broadway musical “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” — whose hard, boozy living and freewheeling prose captured and exemplified the era.

“It seemed like they were living lives of joy and engagement and with a sense of recklessness that was beyond the reach of most of us,” Joe Holley, a columnist and editorial writer for The Houston Chronicle, said in an interview. “They lived hard. They wrote well, and they seemed to be intensely alive.

“What we didn’t realize until later, when the heart attacks began and when they started writing confessional memoirs, was that hard living exacted a price.”

Mr. Cartwright published another memoir, The Best I Recall, in 2015. He also wrote screenplays and novels.

He was born in Dallas in 1934 and grew up in the tiny West Texas oil town of Royalty in the late 1930s. With defense plants in the Dallas-Fort Worth area hiring after the start of World War II, the family moved to Arlington, the Dallas suburb, where his mother worked in a dress shop. His father worked at a defense plant in Fort Worth.

After high school Mr. Cartwright attended Arlington State College and the University of Texas, enlisted in the Army for a two-year stateside stint and earned his bachelor’s degree afterward at Texas Christian University.

He got his start in journalism in the mid-1950s, covering the police and sports for newspapers in Fort Worth and Dallas. He became the anchor of Texas Monthly and mentored a generation of young journalists, including Nicholas Lemann, the author and former dean of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

“Gary was a Texas news guy to the core — somebody who grew up in old-school, smoke-filled, blue-collar newsrooms and went on to become one of the first Texas journalists to make a national reputation in long-form journalism,” Mr. Lemann said.

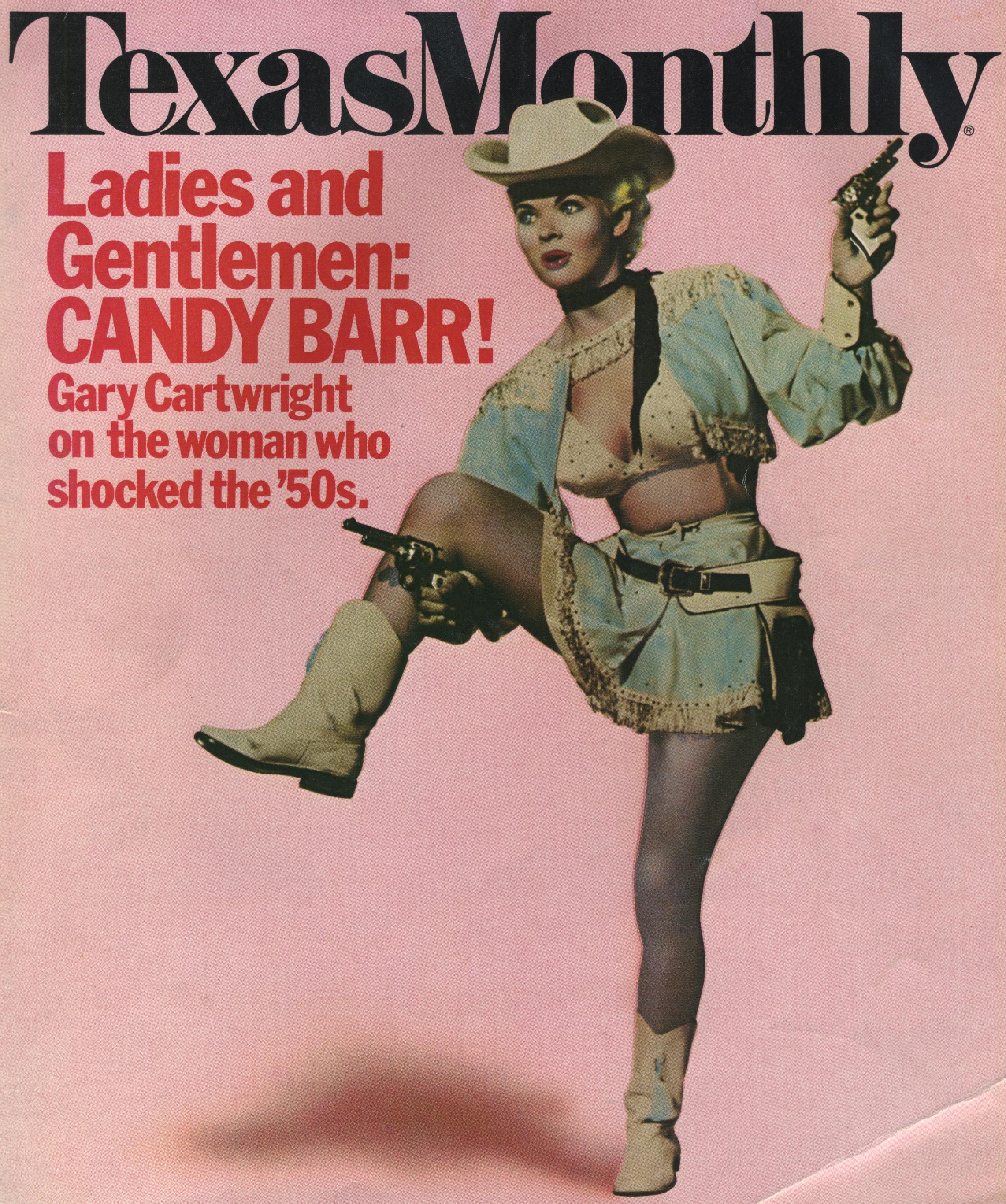

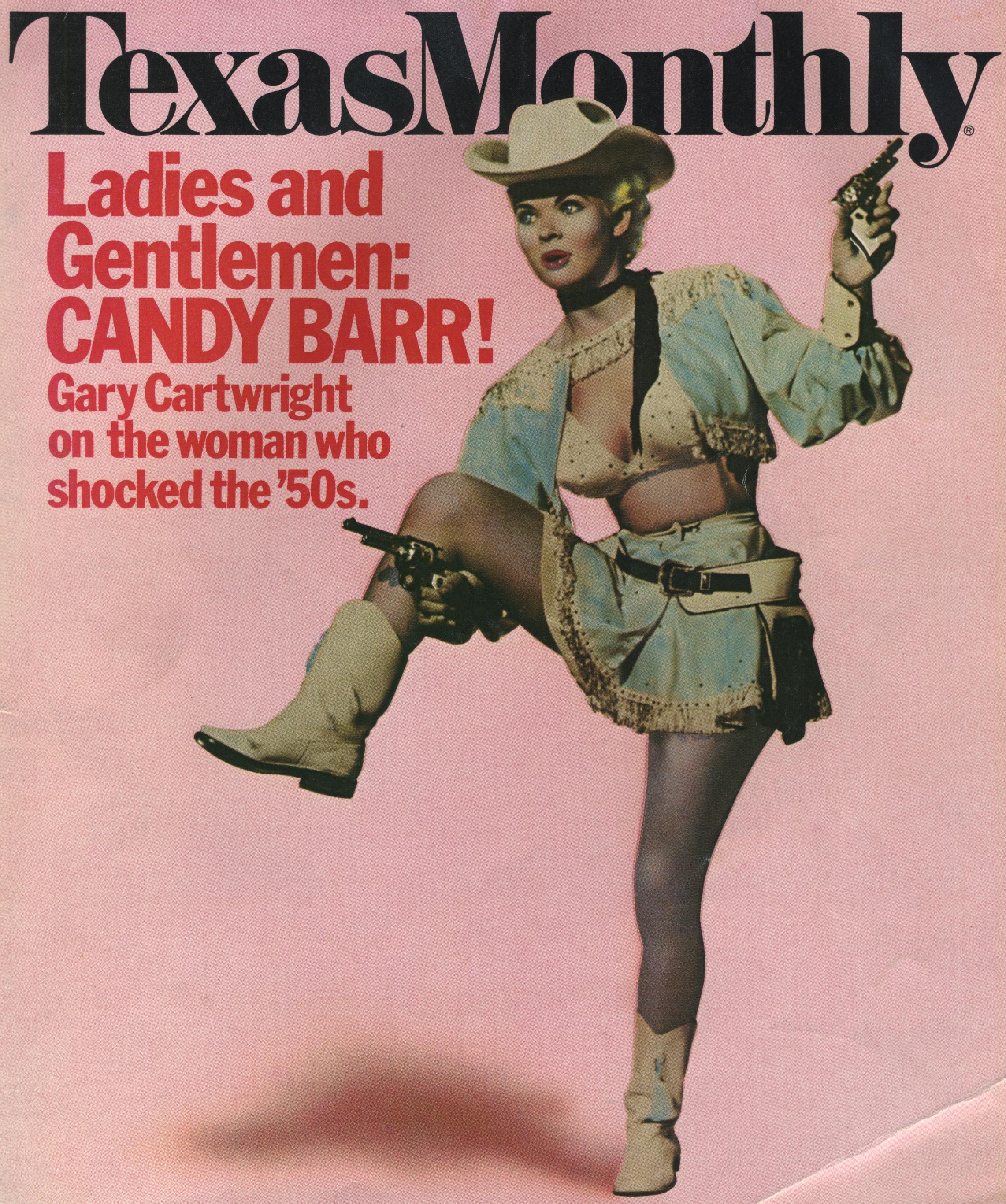

The opening of Cartwright’s great 1976 Texas Monthly profile of notorious Dallas stripper Juanita Dale Slusher, aka Candy Barr:

On the road home to Brownwood in her green ’74 Cadillac with the custom upholstery and the CB radio, clutching a pawn ticket for her $3000 mink, Candy Barr thought about biscuits. Biscuits made her think of fried chicken, which in turn suggested potato salad and corn. For as long as she could remember, in times of crisis and stress, Candy Barr always thought of groceries. It was a miracle she didn’t look like a platinum pumpkin, but she didn’t: even at 41, she still looked like a movie star.

For once, the crisis was not her own. It was something she had read a few days earlier about how the omnipotent, totalitarian they were about to jackboot the remnants of the once happy and prosperous life of a 76-year-old Dallas electrician named O. E. Cole. Candy had never heard of O. E. Cole until she spotted his pitiful tale in the Brownwood newspaper. She didn’t know if Cole was black or white, mean or generous, judgmental or forgiving. She only knew he was in trouble. For nearly fifty years Cole had been an upright, hardworking citizen of a city Candy Barr had every reason to hate; then his wife Nettie suffered a stroke and lingered in a coma for eighteen months while their savings were sucked away. According to the newspaper account, Cole spent $500 for Nettie’s headstone, which left him a balance of $157. Before he could use that money to cover mortgage payments on his home and the electrician’s shop at the back, a gunman shot and robbed him. Now, when he was too old to apply for additional credit, they were prepared to foreclose.

“This is a goddamn crime!” Candy raged, throwing her suitcase on the bed and barking a string of orders to her houseguests: Scott, her 22-year-old boyfriend of the moment, and Susan Slusher, her 17-year-old niece who had recently come to stay with “Aunt Nita” from a broken home in Philadelphia.

Scott and Susan had been around just long enough to know that when Candy blew—as often as she did without warning—to look not for explanations but for something sturdy to hang onto. Try to imagine a hurricane in a Dixie Cup. The laughing tropical green eyes boiled, and the innocence that had made that perfect teardrop face a landmark in the sexual liberation of an entire generation of milquetoasts became the wrath of Zeus. They say she once sat waiting in a rocking chair talking to sweet Jesus and when her ex-husband kicked down the door she threw down on him with a pistol that was resting conveniently in her lap. She shot him in the stomach, but she was aiming for the groin. When she caught mobster Mickey Cohen talking to another woman, she slugged him in the teeth. She carved her mark on a dyke in the prison workshop: this was not a lovers’ quarrel, as an assistant warden indicated on her record, but a disagreement stemming from Candy’s hard-line belief that a worker should take pride in her job.

Candy had a cosmic way of connecting things, which to the more prosaic mind might appear coincidental. So it was that the ill-fated placement of a Citizens National Bank of Brownwood ad next to the article outlining the plight of O. E. Cole ignited her fuse. The bank ad suggested that had it not been for a Revolutionary War banker named Robert Morris, we might all be sipping tea with crumpets and begging God to save our Queen. What the average eye might take as harmless Bicentennial puffery hit Candy’s heart dead center.

“I watched the bastards do the same thing to my daddy,” Candy fumed, removing her mink from the cedar chest and raking bottles and jars of cosmetics into her overnight bag. “I sold my hunting rifle three times to help my daddy. It’s a crime what they can do to people, a goddamn crime. Don’t call me a criminal if you’re gonna be one.”

With the skillful employment of her CB radio, “The Godmother” and her two young companions made the 160 miles to Dallas in less that two hours. Candy hocked her mink for $250, then called on dancer Chastity Fox and other friends to help raise another $150. Then Candy painted her face with soft missionary shades of tan and gold and called on O. E. Cole, introducing herself as Juanita Dale Phillips of Brownwood and presenting the goggle-eyed electrician with $400 and a copy of her book of prison poems, A Gentle Mind … Confused. Cole couldn’t have been more confused if he had found Fidel Castro in his refrigerator. When I spoke with Cole two weeks later, there were still some blank spaces behind his eyes, but the crisis had passed.

“I didn’t know who she was till I saw her name on that little book,” he told me. “Oh, yes, I knew the name Candy Barr. You couldn’t live in Dallas long as I had and not know that name. But it wasn’t for me to judge her. What is past is past. It’s what a person is now I go on, and she was awful nice. We sat around and talked for hours. In fact, we talked all night long.”•