pats hater???

hey, what’s up. i am looking for a pats hater to help a patriots fan make good on a pretty humiliating bet when down in nyc from mass. it’s all in good fun and you get some cash too. hit me up….

Ideas and technology and politics and journalism and history and humor and some other stuff.

Charity Johnson was interested in second chances, and so were her many mothers. A 34-year-old woman recently arrested for impersonating a tenth-grader in Texas, the pretend teen desired only to be a child whose love could not be refused by maternal figures, whose embrace could never be turned away. A daughter of abuse and neglect, she would not be cheated of what she never had and always wanted.

She’s not the first person to crave an infinite loop of adolescence–a period most of us were happy to escape–and she won’t be the last. Adults stuck in a particular time in childhood tend to have suffered a serious, unresolved wound at that age. But why does this extreme and specific type of need exist in some who had awful upbringings but not in others? And why isn’t this yearning fulfilled during the initial masquerade? Why is it serial, the hunger never sated? From Katie J.M. Baker at Buzzfeed:

“Longview, population 81,000, is a charmless city with nothing to do but hang out at churches and chain restaurants. But Charity seemed content. After school, she worked and spent time with her classmates and ‘mom,’ Tamica Lincoln, a 30-year-old McDonald’s breakfast manager whom Charity moved in with in the spring. She posted Instagram photos of friendship bracelets, cookies ‘split with friends,’ and smiling teenage boys on a spring break trip to a nearby Christian university. She loved making her own Instagram ‘art’: selfies juxtaposed with sayings like ‘Baby I’m a star’ and ‘Honeybee, love me.’ Earlier this year, she posted a photo that read ‘My mommy was my best friend…’

‘Love ur mom with your all cuz n a split second u cld lose her..’ she wrote below the picture.

Charity has loved and lost so many ‘moms’ that it’s hard to keep track. Some of them reached out to Tamica when Charity’s mugshot made international headlines in May. That’s when Charity was arrested for intentionally giving false information to a police officer who received a tip that she was much older than her hair bows implied. Soon, outlets from Good Morning America to the Daily Mail were calling Charity’s devastated schoolmates (they still miss her, according to a recent ABC News follow-up) and bewildered 23-year-old boyfriend (he said he thought she was 18).

For years, Charity had targeted devout, maternal types with regrets and a weakness for lost, young souls. Women all over Texas, as well as North Carolina, New Jersey, and Maryland, said they had combed Charity’s hair, helped her with her homework, and given her a bed to sleep in. Up until her arrest, Charity kept in close contact with her collection of online ‘mothers,’ from a housekeeper in Nevada to a pastor in Ohio, whom she found through Facebook searches (‘pastor’ + ‘teen girls’ + ‘hope’).

Most of them cut ties with Charity after she was exposed as a 34-year-old living what Time called ‘Never Been Kissed IRL.’ (Time misreported her as being 31 at the time.) But Charity made an impact in Longview, where many of the friends, mentors, and makeshift family members she met are still mourning her loss. They haven’t seen or talked to Charity since she pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor (for failing to identify herself to a police officer) after 29 days in jail and left town, but they don’t feel betrayed. Instead, they asked me for her phone number in hopes they could convince her to come back. They’re all deeply religious Christians who grew up in broken homes or even spent time on the streets before they were ‘saved.’ They wanted, and still want, to help Charity follow in their footsteps and succeed as an adult.”

Tags: Charity Johnson, Katie J.M. Baker

From the March 2, 1949 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“Seattle — Will K. Sugden said today his romance with his bride of 14 weeks, an amnesia victim, had progressed beyond the hand-holding stage.

‘She’s coming my way,’ he said. ‘She lets me kiss her now. She’ll love me again.’

Sugden’s bride, Hertis, 26, suffered amnesia two weeks ago. She forgot her husband and his two children by a previous marriage.”

Tags: Hertis Sugden, Will K. Sugden

The Olympics are never mostly about the sports. They’re an examination of contemporary geopolitics, a survey of the latest media and technology and a narrative about the host nation, which presents not just itself, but its aspirations, to the world. Of course, such an idealization can have short shelf life. After the success of Sochi, Russia seemed pointed toward the future, perhaps becoming another modern Germany with its technological might and post-conflict politics, but the country was quickly yanked back into the 20th century by Putin’s folly.

Even when the aftermath doesn’t undo the good will, the cost of such an event is beyond onerous. From an Economist article about the buyer’s remorse of Tokyo, the “winner” of the 2020 Games:

“Disquiet over construction plans has been heightened by growing concerns about cost. Estimates for the stadium refurbishment have more than doubled as construction and labour costs have soared under Abenomics, Japan’s bid to end years of deflation. City officials revealed recently that this year’s consumption-tax hike of 3% was not even factored into the original budget. Cost concerns may now force some venues out of the expensive city to the far-flung suburbs.

The 1964 event cost many times more than its predecessor in Rome four years earlier, and added to the Olympics’ spendthrift reputation—not a single games since then has met its cost target. The Tokyo Olympics also triggered the start of Japan’s addiction to bond issuance, which continues unabated today. Tokyo’s original estimate of ¥409 billion ($3.7 billion) for the games now looks unrealistic to most critics. If, as some expect, Abenomics runs out of steam, the city faces a painful post-games hangover.”

My preference would be to live forever–and I don’t mean metaphorically–but my (somewhat) more realistic goal is to reach 100. Of course, just like you and everyone you know, I could go in the next minute. I just don’t want to.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel wants to. Not right now, but soon, before he believes aging becomes nasty and burdensome for him and his loved ones. I think he’s giving short shrift to gerontological advances, but to each his own. The opening of his latest Atlantic article, “Why I Hope to Die at 75“:

“Seventy-five.

That’s how long I want to live: 75 years.

This preference drives my daughters crazy. It drives my brothers crazy. My loving friends think I am crazy. They think that I can’t mean what I say; that I haven’t thought clearly about this, because there is so much in the world to see and do. To convince me of my errors, they enumerate the myriad people I know who are over 75 and doing quite well. They are certain that as I get closer to 75, I will push the desired age back to 80, then 85, maybe even 90.

I am sure of my position. Doubtless, death is a loss. It deprives us of experiences and milestones, of time spent with our spouse and children. In short, it deprives us of all the things we value.

But here is a simple truth that many of us seem to resist: living too long is also a loss. It renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived. It robs us of our creativity and ability to contribute to work, society, the world. It transforms how people experience us, relate to us, and, most important, remember us. We are no longer remembered as vibrant and engaged but as feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic.

By the time I reach 75, I will have lived a complete life. I will have loved and been loved. My children will be grown and in the midst of their own rich lives. I will have seen my grandchildren born and beginning their lives. I will have pursued my life’s projects and made whatever contributions, important or not, I am going to make. And hopefully, I will not have too many mental and physical limitations. Dying at 75 will not be a tragedy.”

Tags: Ezekiel J. Emanuel

If a Hollywood producer is looking for a niche market to exploit, I would suggest he or she target America. In a globalized world, the U.S. is but another player on the stage, and films that target a specifically American sensibility aren’t really the point anymore. Want to make a movie about baseball or Boise? Not so likely now.

Terry Gilliam has pretty much had it with Hollywood. While the visionary director never had a niche geographically, he was the director who made the mid-budget film that was dazzling and adventurous and often brilliant, though sometimes it fell apart. From an interview the filmmaker did with Andrew O’Hehir at Salon:

“Question:

Well, and then there’s your relationship with the film industry, which was maybe never so terribly warm and fuzzy. Is that that you have changed or that the nature of the mainstream film industry has changed? Or have the two of you just sort of drifted further apart?

Terry Gilliam:

I think we’ve both changed and probably drifted apart for that reason, even more. In Hollywood, at least when I was making films there, there were people in the studios that actually had personalities. You could distinguish one from the other. And now, I don’t see that at all. It’s just gray, frightened people holding on without any sense of “let’s try something here, let’s do something different.” But to be fair, I haven’t been talking to anybody from the studios in the last few years. But the films that Hollywood is making now, it’s clear what’s going on. The big tent-pole pictures are just like the last tent-pole pictures. Hopefully one of them will work and keep the studio going. It’s become … it’s a reflection of the real world, where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer and the middle class get squeezed out completely. So the kind of films I make need more money than the very simple films. Hollywood doesn’t deal with those budgets anymore; they don’t exist.

Question:

You can’t make the film in your house for $50,000. But they’re also not going to give you $100 million. You’re in a mid-budget area they don’t like, right?

Terry Gilliam:

Yeah. It’s terrible. I’m not alone in the mid-budget area that’s being pushed out of work. It’s a great sadness because there are many small films that can be wonderful, or you get huge $100 million-plus budgets and they’re all the same film, basically, or very similar. It’s just not as interesting as it used to be. The choice out there is less interesting. The real problem now is that when you make a small film, to get the money to promote it is almost impossible. You can’t complete with a $70-80 million budget the studios have. So it becomes less and less interesting. That’s why, in a sense, the most interesting work at the moment, as any creative person, knows is coming out of television in America now, not coming out of the studios.

Question:

The studios have two niches, and the problem is that you don’t fit in either one of them. You’re not going to do a Transformers movie for $250 million. And they think you’re not the right person to do the movie that maybe costs $40 million and is aimed at the Oscars, or is a prestige literary adaptation or something. They don’t trust you with those, right?

Terry Gilliam:

I wouldn’t trust me with them either. [Laughs.] I just want to do what I do. And I don’t even get scripts from Hollywood. I don’t even ask for scripts anymore because I kind of know what they’re going to be. They don’t interest me, so I’ve chosen to wander in the wilderness for another 40 years. We’ll see how it goes.”

Tags: Andrew O'Hehir, Terry Gilliam

The Red Sox brass’ attempts at rewiring their batters’ brains didn’t pay dividends during the team’s woeful 2014 season, but we’re just at the beginning of cognitive experimentation. PEDs will be seen as crude rudiments compared to what will eventually be permitted on and off the field of play. From Brian Costa at the Wall Street Journal:

“Take a peek inside the frazzled mind of a major-league hitter these days. It isn’t a pretty sight.

Pitchers are throwing harder than ever. Batters are striking out more often than ever. And their judgment is getting shakier: Hitters are chasing more pitches outside the strike zone.

It is enough to make some teams wonder: What if we could just rewire hitters’ brains to react to pitches better? As it turns out, at least three major-league teams are engaged in a covert science experiment to find out.

Several years ago, the Boston Red Sox began working with a Massachusetts neuroscience company called NeuroScouting. The objective was to develop software that could improve hitters’ ability to recognize pitch types and decide, with greater speed and accuracy, whether they should swing. The result was a series of no-frills videogames that became a required part of hitters’ pregame routines in the minor leagues.”

Tags: Brian Costa

In a Financial Times essay, economist Tim Harford finds a link no one else was looking for: the scorched-earth strategies which drive both Amazon and contemporary Russia. An excerpt:

“Brad Stone’s excellent book, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, paints Amazon’s founder to be a visionary entrepreneur, dedicated to serving his customers. But it also reports that Bezos was willing to take big losses in the hope of weakening competitors. Zappos, the much-loved online shoe retailer, faced competition from an Amazon subsidiary that first offered free shipping and then started paying customers $5 for every pair of shoes they ordered. Quidsi, which ran Diapers.com, was met with a price war from “Amazon Mom.” Industry insiders told Stone that Amazon was losing $1m a day just selling nappies. Both Zappos and Quidsi ended up being bought out by Amazon.

When the weapons of war are low prices, consumers benefit at first. But the long term looks worrying: a future in which nobody dares to compete with Amazon. Apple is a striking contrast: the company’s refusal to compete aggressively on price makes it hugely profitable but has also attracted a swarm of competitors.

Consider a grimmer parallel. Vladimir Putin’s Russia is the chain store. Georgia, Ukraine and many other former Soviet states or satellites must consider whether to seek ties with the west. In each case Putin must decide whether to accommodate or open costly hostilities. The conflict in Ukraine has been disastrous for Russian interests in the short run but it may have bolstered Putin’s personal position. And if his strategy convinces the world that Putin will never share prosperity, his belligerence may yet pay off.

I feel a little guilty comparing Bezos and Putin. My only regret about Bezos’s Amazon is that there aren’t three other companies just like it. I do not feel the same about Putin’s Russia.”

Tags: Brad Stone, Jeff Bezos, Tim Harford, Vladimir Putin

I previously posted a 1955 New York Times interview which Thomas Mann sat for near the end of his life, and below I’ve put a piece from a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article about him that ran in the April 18, 1937 edition, when he was living in America, an exile from Nazi Germany during the run-up to World War II. He seemed confident about the fall of fascism. I never read before that he’d dined with FDR, though it makes sense given the writer’s Nobel stature and his social nature. The piece was written by Alvah Bessie, who a decade later was to be blacklisted and imprisoned by HUAC as a member of the “Hollywood Ten,” along with Dalton Trumbo.

Tags: Alvah Bessie, Thomas Mann

10 search-engine keyphrases bringing traffic to Afflictor this week:

This week, John Boehner said unemployed Americans would rather “just sit around” and not work. He has a point. People who just sit around and do nothing shouldn’t be given free money.

Unlike many of his friends and neighbors, an Iraqi teenager named Khidir only pretended to be murdered in August after he was herded with others into a mass execution by members of ISIS. The opening of a survivor’s story, as told by Lauren Bohn in Foreign Policy:

“Duhok, Iraq — One sunny day this summer, 17-year-old Khidir lay on the ground and pretended to be dead for what seemed like an eternity.

On Aug. 15, masked Islamic State (IS) militants stormed into his village, Kocho, about 15 miles southwest of the town of Sinjar, ordering hundreds to gather in the village’s only school. There they took everyone’s mobile phones and valuable possessions — wedding rings, money, life savings, all gone in a flash. They told the villagers not to worry, that they would simply drive them all to Mount Sinjar to be with their fellow Yazidi people, who practice an ancient religion considered heretical to the Islamic extremists.

‘We had heard they might come to the village, but we didn’t actually believe they would,’ says Khidir, his hands brushing against a dirty white bandage on his neck.

They told Khidir he’d be among the first group of men to leave. A wave of relief washed over him. ‘I thought that maybe they weren’t so evil as we had thought,’ he recalls.

He and 20 or so other men piled into a white Kia truck, unnerved to be separated from their families but hopeful about reaching the mountain, where thousands of Yazidis had fled from the Islamic State’s advance. About 10 minutes later, the truck stopped in the middle of a field, where two other men were waiting with machine guns. Khidir suddenly realized they weren’t going to the mountain after all.”

Tags: Lauren Bohn

Photographs aren’t life or memory, but in a time of cheap, ubiquitous cameras, the image, merely an imitation, is ascendant. Like the tree’s lonely fall in the forest, the event unrecorded has less currency. Without capture, does the moment even exist anymore? On some levels, no. From “We Are a Camera,” Nick Paumgarten’s New Yorker piece about living in the GoPro flow:

“For two days in the Idaho mountains, [mountain biker Aaron] Chase’s cameras had been rolling virtually non-stop. Now, with his companions lagging behind, he started down the trail, which descended steeply into an alpine meadow. As he accelerated, he noticed, to his left, an elk galloping toward him from the ridge. He glanced at the trail, looked again to his left, and saw a herd, maybe thirty elk, running at full tilt alongside his bike, like a pod of dolphins chasing a boat. After a moment, they rumbled past him and crossed the trail, neither he nor the elk slowing, dust kicking up and glowing in the early-evening sun, amid a thundering of hooves. It was a magical sight. The light was perfect. And, as usual, Chase was wearing two GoPros. Here was his money shot—the stuff of TV ads and real bucks.

Trouble was, neither camera was rolling. What with his headache and the ample footage of the past days, he’d thought to hell with it, and had neglected, just this once, to turn his GoPros on. Now there was no point in riding with the elk. He slowed up and let them pass. ‘Idiot,’ he said to himself. ‘There goes my commercial.’

Once the herd was gone, it was as though it’d never been there at all—Sasquatch, E.T., yeti. Pics or it didn’t happen. Still, one doesn’t often find oneself swept up in a stampede of wild animals. Might as well hope to wingsuit through a triple rainbow. So you’d think that, cameras or not, he’d remember the moment with some fondness. But no. ‘It was hell,’ Chase says now.

When the agony of missing the shot trumps the joy of the experience worth shooting, the adventure athlete (climber, surfer, extreme skier) reveals himself to be something else: a filmmaker, a brand, a vessel for the creation of content. He used to just do the thing—plan the killer trip or trick and then complete it, with panache. Maybe a photographer or film crew tagged along, and afterward there’d be a slide show at community centers and high-school gyms, or an article in a magazine. Now the purpose of the trip or trick is the record of it. Life is footage.”

Tags: Aaron Chase, Nick Paumgarten

Yahoo! doesn’t know what it wants to be, while Google wants to be everything. It’s clear Larry Page would like to do radical experiments on the micro scale, but he really dreams of the macro, hoping to establish a next-wave Google to tackle the world’s non-virtual problems. From Vlad Savov at The Verge:

“As if self-driving cars, balloon-carried internet, or the eradication of death weren’t ambitious enough projects, Google CEO Larry Page has apparently been working behind the scenes to set up even bolder tasks for his company. The Information reports that Page started up a Google 2.0 project inside the company a year ago to look at the big challenges facing humanity and the ways Google can overcome them. Among the grand-scale plans discussed were Page’s desire to build a more efficient airport as well as a model city. To progress these ideas to fruition, the Google chief has also apparently proposed a second research and development lab, called Google Y, to focus on even longer-term programs that the current Google X, which looks to support future technology and is headed up by his close ally Sergey Brin.”

Tags: Larry Page, Vlad Savov

E.O. Wilson has a bold plan for staving off a mass extinction of life on Earth: radical biodiversity ensured by demarcation. The evolutionary biologist wants humans to “rope off” half the planet for non-human species. Tony Hiss, the longtime New Yorker writer who did some wonderful work for that publication (like this and this) has an article in Smithsonian about Wilson’s bold proposal. An excerpt:

Throughout the 544 million or so years since hard-shelled animals first appeared, there has been a slow increase in the number of plants and animals on the planet, despite five mass extinction events. The high point of biodiversity likely coincided with the moment modern humans left Africa and spread out across the globe 60,000 years ago. As people arrived, other species faltered and vanished, slowly at first and now with such acceleration that Wilson talks of a coming “biological holocaust,” the sixth mass extinction event, the only one caused not by some cataclysm but by a single species—us.

Wilson recently calculated that the only way humanity could stave off a mass extinction crisis, as devastating as the one that killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, would be to set aside half the planet as permanently protected areas for the ten million other species. “Half Earth,” in other words, as I began calling it—half for us, half for them. A version of this idea has been in circulation among conservationists for some time.

“It’s been in my mind for years,” Wilson told me, ‘that people haven’t been thinking big enough—even conservationists. Half Earth is the goal, but it’s how we get there, and whether we can come up with a system of wild landscapes we can hang onto. I see a chain of uninterrupted corridors forming, with twists and turns, some of them opening up to become wide enough to accommodate national biodiversity parks, a new kind of park that won’t let species vanish.”•

Tags: Anthony Hiss, E.O Wilson

In an excellent New York Times Magazine article that completely untangles for the first time the players and particulars of the Gary Hart political scandal of 1987, Matt Bai reminds us what was lost for good when a confluence of factors brought down the front-runner for the American Presidency. Hart was an astute observer of his time, aware long before his peers that stateless terrorism and the Information Age were twin challenges that would soon require aggressive management. But his mastery of the moment was laid to waste by indiscretion. The Colorado candidate wasn’t collared only by ego, stupidity and the media’s shifting rules of engagement–when the get became more important than what was gotten, when the political became truly personal–but seemingly by a streak of common jealousy. An excerpt about a key figure who escaped notice at the time:

Dana Weems wasn’t especially hard to find, it turned out. A clothing designer who did some costume work on movies in the early 1990s, she sold funky raincoats and gowns on a website called Raincoatsetc.com, based in Hollywood, Fla. When she answered the phone after a couple of rings, I told her I was writing about Gary Hart and the events of 1987.

“Oh, my God,” she said. There followed a long pause.

“Did you make that call to The Herald?” I asked her.

“Yeah,” Weems said with a sigh. “That was me.”

She then proceeded to tell me her story, in a way that probably revealed more about her motives than she realized. In 1987, Armandt sold some of Weems’s designs at her bikini boutique under a cabana on Turnberry Isle. Like Rice, Weems had worked as a model, though she told me Rice wasn’t nearly as successful as she was. Rice was an artificial beauty who was “O.K. for commercials, I guess.”

Weems recalled going aboard Monkey Business on the last weekend of March for the same impromptu party at which Hart and his pal Billy Broadhurst, a Louisiana lawyer and lobbyist, met up with Rice, but in her version of events, Hart was hitting on her, not on Rice, and he was soused and pathetic, and she wanted nothing to do with him, but still he followed her around the boat, hopelessly enthralled. . . .

But Donna — she had no standards, Weems told me. Weems figured Donna wanted to be the next Marilyn Monroe, sleeping her way into the inner sanctum of the White House, and that’s why she agreed to go on the cruise to Bimini. After that weekend, Donna wouldn’t shut up about Hart or give the pictures a rest. It all made Weems sick to her stomach, especially this idea of Hart’s getting away with it and becoming president. “What an idiot you are!” Weems said, as if talking to Hart through the years. “You’re gonna want to run the country? You moron!”

And so when Weems read Fiedler’s story in The Herald, she decided to call him, while Armandt stood by, listening to every word. “I didn’t realize it was going to turn into this whole firecracker thing,” she told me. It was Armandt’s idea, Weems said, to try to get cash by selling the photos, and that’s why she asked Fiedler if he might pay for them (though she couldn’t actually remember much about that part of the conversation). Weems said she hadn’t talked to either woman — Rice or Armandt — since shortly after the scandal. She lived alone and used a wheelchair because of multiple sclerosis. She was surprised her secret had lasted until now.

“I’m sorry to ruin his life,” she told me, offhandedly, near the end of our conversation. “I was young. I didn’t know it would be that way.”•

Tags: Dana Weems, Gary Hart, Matt Bai

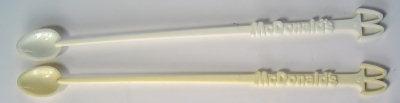

In a Priceonomics post, Zachary Crockett recalls the insidious repurposing of a seemingly innocuous tool, the McDonald’s plastic coffee spoon, which became, in the 1970s, a handheld device for coke dealers and users, as well as a pawn in the early years of the War on Drugs. The opening:

“In the 1970s, every McDonald’s coffee came with a special stirring spoon. It was a glorious, elegant utensil — long, thin handle, tiny scooper on the end, each pridefully topped with the golden arches. It was a spoon specially designed to stir steaming brews, a spoon with no bad intentions.

It was also a spoon that lived in a dangerous era for spoons. Cocaine use was rampant and crafty dealers were constantly on the prowl for inconspicuous tools with which to measure and ingest the white powder. In the thralls of an anti-drug initiative, the innocent spoon soon found itself at the center of controversy, prompting McDonald’s to redesign it. In the years since, the irreproachable contraption has tirelessly haunted the fast food chain.

It was also a spoon that lived in a dangerous era for spoons. Cocaine use was rampant and crafty dealers were constantly on the prowl for inconspicuous tools with which to measure and ingest the white powder. In the thralls of an anti-drug initiative, the innocent spoon soon found itself at the center of controversy, prompting McDonald’s to redesign it. In the years since, the irreproachable contraption has tirelessly haunted the fast food chain.

This is the story of how the ‘Mcspoon’ became the unlikely scapegoat of the War on Drugs.”

Tags: Zachary Crockett

From the August 5, 1911 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“Topeka, Kan. — Shaving of all cats is recommended by the State Board of Health of Kansas as a means of preventing the spread of disease.

The board charges that the cat, with its long hair, carries more germs than any other animal.

‘Shave the cats,’ said Dr. Deacon of the State Board of Health, yesterday. ‘Keep their hair short just like you would a horse’s or a dog’s. If that is too much trouble, kill them.'”

Tags: Dr. Deacon

EVs don’t help the environment much unless the electricity is being produced in green, alternative ways, and solar homes won’t become common until they’re more affordable. Elon Musk of Tesla and his cousin Lyndon Rive of SolarCity are trying to power those potential markets with multiple uses of the planned Nevada Gigafactory. From “The Musk Family Plan for Transforming the World’s Energy,” Christopher Mims’ new WSJ piece:

“Thanks to the economies of scale that will come from Tesla’s gigafactory, within 10 years every solar system that SolarCity sells will come with a battery-storage system, says Mr. Rive, and it will still produce energy cheaper than what is available from the local utility company.

Mr. Musk also noted that in any future in which a country switches fully to electric cars, its electricity consumption will roughly double. That could either mean more utilities, and more transmission lines, or a rollout of solar—exactly the sort that SolarCity hopes for.

America’s solar energy generating capacity has grown at around 40% a year, says Mr. Rive. ‘So if you just do the math, at 40% growth in 10 years time that’s 170 gigawatts a year,’ says Mr. Rive. That’s equivalent to the electricity consumption of about 5 million homes, which is still ‘not that much,’ he says, when compared with overall demand for electricity. ‘It’s almost an infinite market in our lifetimes.’

There are almost innumerable barriers to the realization of Messrs. Musk and Rive’s plan.”

Tags: Christopher Mims, Elon Musk, Lyndon Rive

A gigantic prison population in the U.S. has unsurprisingly begat an intricate illicit social order behind bars. The crime hasn’t truly disappeared–it’s just been disappeared into cells. From Graeme Wood’s new Atlantic article, “How Gangs Took Over Prisons“:

“Understanding how prison gangs work is difficult: they conceal their activities and kill defectors who reveal their practices. This past summer, however, a 32-year-old academic named David Skarbek published The Social Order of the Underworld, his first book, which is the best attempt in a long while to explain the intricate organizational systems that make the gangs so formidable. His focus is the California prison system, which houses the second-largest inmate population in the country—about 135,600 people, slightly more than the population of Bellevue, Washington, split into facilities of a few thousand inmates apiece. With the possible exception of North Korea, the United States has a higher incarceration rate than any other nation, at one in 108 adults. (The national rate rose for 30 years before peaking, in 2008, at one in 99. Less crime and softer punishment for nonviolent crimes have caused the rate to decline since then.)

Skarbek’s primary claim is that the underlying order in California prisons comes from precisely what most of us would assume is the source ofdisorder: the major gangs, which are responsible for the vast majority of the trade in drugs and other contraband, including cellphones, behind bars. ‘Prison gangs end up providing governance in a brutal but effective way,’ he says. ‘They impose responsibility on everyone, and in some ways the prisons run more smoothly because of them.’ The gangs have business out on the streets, too, but their principal activity and authority resides in prisons, where other gangs are the main powers keeping them in check.

Skarbek is a native Californian and a lecturer in political economy at King’s College London. When I met him, on a sunny day on the Strand, in London, he was craving a taste of home. He suggested cheeseburgers and beer, which made our lunch American not only in topic of conversation but also in caloric consumption. Prison gangs do not exist in the United Kingdom, at least not with anything like the sophistication or reach of those in California or Texas, and in that respect Skarbek is like a botanist who studies desert wildflowers at a university in Norway.

Skarbek, whose most serious criminal offense to date is a moving violation, bases his conclusions on data crunches from prison systems (chiefly California’s, which has studied gangs in detail) and the accounts of inmates and corrections officers themselves. He is a treasury of horrifying anecdotes about human depravity—and ingenuity. There are few places other than a prison where men’s desires are more consistently thwarted, and where men whose desires are thwarted have so much time to think up creative ways to circumvent their obstacles.”

Tags: David Skarbek, Graeme Wood

My fellow Americans, if you dipshits can stop beating the snot out of each other in elevators for five fucking minutes, I have something to say to you.

In 2009, I took over the governance of a badly damaged country from an alcoholic who couldn’t find oil in Texas.

But nothing I do pleases you geniuses. Even Obamacare, a rousing success by every measure, is hated by the very people who need it most.

Despite my best efforts, the world has become even dumber. I waxed Osama bin Laden and now they’ve got terrorists who wear Rolexes.

Domestically, things are just as stupid. You rocket scientists want your crossing guards armed with howitzers.

I’ve added jobs for 55 straight months despite dealing with a do-nothing Congress, and you babies continue to whine.

We know that Colony Collapse Disorder is the result of bees being stressed to death by a number of factors, but contagious illnesses transmitted by insects (and communicable by other means) can likewise be pressured out of existence if enough of the disease’s agents are countered until the system crashes. From “The Calculus of Contagion,” Adam Kucharski’s excellent Aeon essay about a mathematical approach to preventing potential pandemics like Ebola, a passage about Ronald Ross’ plan of attack for outmaneuvering malaria:

“To prove the connection between mosquitoes and malaria, Ross experimented with birds. He allowed mosquitoes to feed on the blood of an infected bird then bite healthy ones. Not long afterwards, the healthy birds came down with the disease, too. To verify his theory, Ross dissected the infected mosquitoes, and found malaria parasites in their saliva glands. Those parasites turned out to be Plasmodium, identified by a French military doctor who had discovered the bug in the blood cells of infected patients just a few years before.

Next, Ross wanted to show how the disease could be stopped, and his experiment with the water tank pointed the way. Get rid of enough insects, he reasoned, and malaria would cease to spread. To prove his theory, Ross, a keen amateur mathematician, constructed a theoretical model – a ‘mosquito theorem’ – outlining how mosquitoes might spread malaria in a human population. He split people into two groups – healthy or infected – and wrote down a set of equations to describe how mosquito numbers would affect the level of infection in each.

The human and mosquito populations formed a cycle of interactions: the rate at which people got infected depended on the number of times they were bitten by infected mosquitos, which depended on how many such mosquitos there were, which depended on how many humans had the parasite to pass back to those mosquitos, and so on. Ross found that for the disease to simmer along steadily in a population, as it did in India, the number of new infections per month would need to be equal to the number of people recovering from the disease.

Using his model, Ross showed that it wasn’t necessary to remove every mosquito to bring the disease under control. Destroy enough mosquitoes, and people infected with the parasite would recover before they were bitten enough times for the infection to continue at the same level. Therefore, over time, the disease would fall into decline. In other words, the infection had a threshold, with outbreaks on one side and elimination on the other.”

Tags: Adam Kucharski, Ronald Ross